What the AI risks debate is really about

Don't just ask if AI will be powerful, ask who will be in power

In his new book On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything Nate Silver discusses why the discourse around AI risks is so polarized and concludes that people think about AI in very different mental reference classes. These reference classes range from “Math doesn’t WANT things. It doesn’t have GOALS. It’s just math” to “AI is a new species”. In essence, a lot of the AI debate is ‘reference class tennis’ or a ‘battle of analogies’. Making this ‘battle of AI analogies’ more constructive has been a key motivation behind my AI analogies series, which has explored more than a dozen popular AI analogies.

What is new about Nate Silver’s argument is that his “AI Richter scale” offers a way to map AI analogies, which can help to identify where the crux of the disagreement lies. Specifically, we can use it to dissect intuitions about the probability of a catastrophic or existentially bad outcome - p(doom) as some call it - into two components: the probability of AI reaching a specific level of socioeconomic impact + the likelihood of a very bad outcome conditional on AI being in that level of socioeconomic importance.

As

has argued in What the AI debate is really about most of the disagreements about AI risks are implicit disagreements about how impactful AI will be. In other words, most AI risk sceptics are not sceptical that superintelligence would come with serious risks if it is developed, they are sceptical that superintelligence will be developed in the first place.This post highlights a second important factor to map the AI debate, which divides those believing in very powerful future AI systems. If powerful AI is a tool in the hands of humans, we care about which humans might be empowered by it. If powerful AI is increasingly autonomous and not closely managed or aligned with specific humans, we care about the loss of control. For example, Eliezer Yudkowsky and Leopold Aschenbrenner both believe that we will have very powerful AI systems soon and that there are significant risks. However, Aschenbrenner believes that these AIs will be controlled by humans, Yudkowsky does not. That is the difference between arguing for an ‘AI arms race’ and an ‘AI shutdown’.

1. The AI Richter Scale explained

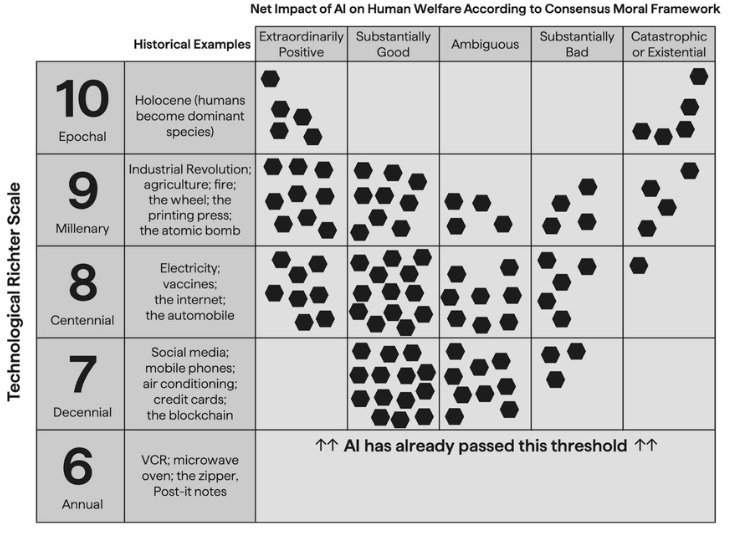

Nate Silver offers the following table with levels of economic, military, and societal impact suggested by AI analogies as the columns (the technological Richter scale) and levels of expected net impact on welfare as the rows.

The Richter scale is traditionally used to quantify the amount of energy released by earthquakes, with each step on the logarithmic scale representing a tenfold increase in power. For example, a magnitude 8 earthquake is ten times more powerful than a magnitude 7. Correspondingly, the idea of his technological Richter scale is that a technology on level 8 (e.g. the Internet) is about 10 times as impactful as a technology on level 7 (e.g. social media).

The categorization of AI analogies on the technological Richter scale is meant to convey high level intuitions. The exact level on which individual technologies should rank can be contested. For example,

has argued that blockchain should rank much lower. There is also a potential asymmetry between AI and the reference technologies on the Richter scale as many of them have existed for a lot longer than AI. The aggregate impact of electricity has accumulated over the last 200 years, so it’s no wonder that electricity has been more impactful.The AI Richter scale helps to be more precise about disagreements

The 100 hexagons used to fill the matrix reflect Nate Silver’s personal probability distribution. Meaning for example Silver believes that there is a 10% chance that AI will have an impact of ‘level 10 - epochal’. He also believes that there is about 10% of AI having a catastrophic or existentially bad impact on human and AI welfare. However, if AI turns out to be “epochal” on the technological Richter scale his conditional probability of a catastrophic or existential outcome is as high as 50%.

As an example, let’s say Expert A puts the probability of a catastrophic or existentially bad outcome from AI at a 1% likelihood. In contrast, Expert B’s intuition is that the likelihood is closer to 50%. So, it seems that they might have a disagreement about the risks of superintelligence, but it is possible that Expert A is a ‘conditional doomer’ and that the experts primarily disagree about the likelihood of superintelligence.

2. The AI agency scale explained

The implicit assumption in Nate Silver’s AI Richter scale is that the history of technology is the only appropriate domain for analogies. However, there are many popular analogies in the AI debate from other domains, most notably biology. Neurobiology is no less than the foundational analogy of the field of artificial neural networks. Furthermore, the relationships between different species offer a broader range of power balances than the relationships of humans to different historical technologies.

The analogies of AI to a pencil, to a gun, to electricity, or to a nuclear bomb suggest different levels of economic, social, and military importance and different levels of risk. However, in all cases, the agency is unmistakably with humans. The traditional ‘autonomy’ scale for cars or trains only considers automation in achieving goals and tasks set by humans. However, one can imagine future AI systems eventually attaining meaningful autonomy in its full social science meaning. Economic autonomy in the sense of AI systems owning themselves (e.g. through a DAO) and freely offering and paying for services rather than being the economic equivalent of a “slave”. Bodily autonomy in the sense of self-directed changes to software, hardware, and effectors. Political autonomy, for example, through co-ownership of a charter city. If such AI systems become more numerous and more powerful than humans, they could outstrip humans in agency as suggested by some analogies.

Analogies do not only suggest a level of agency, they often also suggest a moral evaluation of the potential impact. If we assign the analogies from above into a table with moral outcomes, it provides an approximate intuition for the analogies that people that put a lot of probability mass in a cell would make. The exact placement of any individual analogy is simplified and can be contested.

So, this table can represent a somewhat different set of AI analogies than the technological Richter scale, but does this really add any value as a complement to the AI Richter scale?

What a focus on agency offers as an analytical frame

a) Highlighting what makes AI different

Current LLMs are still below most general-purpose technologies in terms of total, historical socio-economic impact but they are already above them in terms of agency. So, the focus on agency highlights that there is something different about AI, which is outside of the scope of most previous technologies. Yes, LLMs haven’t reached the aggregate economic or military impact of electricity or the nuclear bomb (level 8 & 9) on Silver’s technological richter scale yet. However, even today’s very limited LLMs have much more agency. LLMs can recognize themselves in a ‘mirror’ - nuclear weapons can’t. LLMs can browse the Internet and read this text - nuclear weapons can’t. LLMs can write code - nuclear weapons can’t.

Being aware of both the agency and the socioeconomic impact scales may help to explain why some people have very different intuitions on where we are with AI today and how near some risks are.

b) Misuse vs. loss of control

In analogies in which AI has low or no agency, the primary concern is naturally around the misuse of AI and which fractions of humans are empowered by AI. ‘Guns don’t kill people, people kill people - with guns.’ There is no risk that the nuclear weapons may decide to start a nuclear war by themselves, it’s people that may start a nuclear war - with nuclear weapons.

In contrast, if the mental model is that of independent AGI agents that can increasingly use and make tools, the risk of a gradual or sudden loss of human control is another important factor. Guns don’t kill people, AGI will kill people - with guns. If we would want to phrase this more generally - agents with higher levels of power may be able to instrumentally use agents with lower levels of power. For example, more than six million horses fought in World War 2, but they didn’t fight for horse rights. They were directed by the humans that control them for reasons that they cannot comprehend.

c) Adding alignment expectations

The levels of agency implicitly add expectations about the success of AI alignment into the formula. The probability of AI with superhuman agency is essentially the probability of AI with advanced capabilities + probability of independent AIs.

Eliezer Yudkowsky and Leopold Aschenbrenner both believe that we will have very powerful AI systems soon and that there are some significant risks - so in Nate Silver’s table they would not be positioned very far from each other. However, Eliezer believes that sufficient AI alignment for it to not spin out off human control is nearly impossible and that we are very far from developing such an alignment science. In contrast, Leopold is not without concerns but overall “incredibly bullish on the technical tractability of the superalignment problem”. So, in an agency scale Yudkowsky is closer to the top right, whereas Aschenbrenner is closer to the bottom right1 and they are worried about different types of risks.

Aschenbrenner asks for an arms race to build superintelligence as fast as possible, assuming that it will primarily empower the human groups that build it. “A dictator who wields the power of superintelligence would command concentrated power unlike any we’ve ever seen.” So this is a competition between human superpowers (US vs. China) and what is needed is a national acceleration and export controls to speed up the US and slow down China.

Yudkowsky asks for the opposite - to globally slow down AI or even stop building data centers because interpretability and other research are lagging behind. In his frame humanity is on track to lose control to AI and neither human fraction will have any meaningful power in a superintelligence world. “Shut down all the large GPU clusters (...) Frame nothing as a conflict between national interests, have it clear that anyone talking of arms races is a fool.”

On the surface, their disagreement is whether to accelerate or slow down AI. However, their core disagreement seems to be the prospect of AI alignment. To say it with analogies: A race to build a ‘nuclear bomb’ doesn’t sound that appealing but the fear-based argument that other humans could build it first can be a strong motivator. A race to build uncontrollable ‘aliens’ is not nearly as appealing.

In short, while disagreements about AI risks often appear to revolve around the probability of superintelligent AI, it is also worth considering the level of control and alignment we might retain over powerful AI systems.

Thanks to

, Ben James, , and other Roots of Progress blog-building fellows for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay. All opinions and mistakes are mine.I use Yudkowsky and Aschenbrenner as somewhat idealized archetypes to underline the point of the argument. For example, Aschenbrenner’s Situational Awareness mentions that humans might in fact lose control over AI in the long-run. However, it mostly emphasizes the question of who controls it in the short-run.

Great post! Identifying potentially-unstated differences in worldview is really important for productive discussions of AI, and I think you've put your finger on an important one.