AI Analogies: An Introduction

“About 100 years ago, we started to electrify the United States, (…) that transformed transportation. It transformed manufacturing, using electric power instead of steam power. It transformed agriculture, (…) And I think that AI is now positioned to have an equally large transformation on many industries.” – Andrew Ng, 2017

“The world hasn’t had that many technologies that are both promising and dangerous. We had nuclear weapons and nuclear energy, and so far, so good, although memories seem to be fading on that.”- Bill Gates, 2019

“The aliens are here. They're just not from outer space. AI, which usually stands for artificial intelligence, I think it stands for alien intelligence because AI is an alien type of intelligence.” – Yuval Noah Harari, 2023

Analogies and metaphors provide powerful images of the long-term future of AI and its social, economic, and political consequences, which can in turn have an impact on risk perceptions, legal decisions, and governance structures. However, they are usually proclaimed in isolation. Looking at them in conjunction also highlights underlying tensions and incompatibilities. Maybe AI is like electrification, nuclear weapons, and aliens, but electrification is also clearly not like nuclear weapons, and both are clearly not like aliens.

And that only scratches the surface. Analogies in the global AI debate range from the Anthropocene, to the Cambrian explosion, to chimpanzees, to climate change, to companies, to evolution, to genies, to God, to the human brain, to human occupations, to industrial revolutions, to insects, to mind children, to the neocortex, to oil, to pets, to the printing press, to slavery, to the space race, to the singularity. Only a systematic analysis and comparison of AI analogies can make sense of them.

1. Understanding analogies, metaphors and literal similarities

Analogies

An analogy draws a parallel between two things that are different but share a similar pattern of relationships. The classic form of analogies used in intelligence tests are four-term proportional analogies, in which the relationship A:B is mapped onto the relationship C:D, e.g. hand:finger = foot:toe. I will sometimes restate analogies in this formal format for clarity. However, analogies can also refer to more complex sets of relationships.

A basic function of analogies is that we can take our understanding of relationships in a familiar situation (the source domain), to better understand an unfamiliar situation (the target domain). In a text, analogies usually come along with comparative terms such as “like” or “just as”.

Just as a library is filled with different genres of books, an orchard is filled with a diverse range of apple varieties.

An atom is like a mini solar system: the nucleus is like the sun, and the electrons are like the planets orbiting around it.

Metaphors

In metaphors the source and target domains are blended. They are a creative way of saying one thing is another even if they're not literally the same. Metaphors can be used without an explicit “X is Y” statement by directly using verbs and other terms that imply “X is Y”. Over time, metaphors can turn into a regular meaning of a word.

Pink Lady is in the lead but competing apple varieties such as Cosmic Crisp and RubyFrost are racing to catch up in market share.

The CEO exerts a powerful gravitational pull that directs the orbit of every project in the company.

Literal similarities

A literal similarity points out directly observable attributes shared by two things without the need for abstract or symbolic thinking.

Both apples and strawberries are red.

The TRAPPIST-1 solar system is similar to our solar system with several Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone.

The boundaries between analogies, metaphors, and similarities can be blurred. For example, metaphors can be viewed as a specialized subcategory of analogies rather than as a separate category. Either way, it is still useful to have a rough distinction in mind. Specifically, the AI analogies series is not an evaluation of literal similarities between AI models, such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. It is about comparing the social, economic, environmental, and political characteristics, relationships, and long-term impacts of AI with that of different technologies, projects, time periods, and relationships. The focus is on analyzing analogies, but that will include one or two metaphors.

2. Why analogies matter

Structured comparisons between mental representations are an important part of transfer learning between domains and the human creative process in general. Analogical reasoning can be used in a broad range of contexts from everyday problem solving, to consumer decisions, to scientific theories and innovation, to legal reasoning, to political decisions.

Some, like Douglas Hofstadter, would go as far as arguing that “analogy is the core of all thinking”. However, a much more modest claim is sufficient to justify the analysis of AI analogies. Analogies often play an important role in the governance of emerging technologies (e.g. early Internet), and we should expect AI analogies to have an impact on how AI governance takes shape over the next 5 years.

2.1 Analogies in political decisions

Drawing lessons from history or other domains is one way in which decision-makers navigate through tough policy decisions in uncertain environments. While analogies can also be used an instrumental tool to rationalize and advocate for pre-existing policy preferences, there is evidence that politicians have relied on historical analogies to perform analytical functions and make sense of policy dilemmas. One of the most convincing cases for analogies as an analytical tool is made by Yuen Foong Khong (1992), who has analyzed US decision-making in the Vietnam war, including based on the declassified records of confidential meetings. He showed that analogies:

were not just used in public speeches but in key decision meetings behind closed doors,

helped to inform secondary characteristics of policy choices,

made decision-makers more resistant to opposing evidence.

According to Khong analogies should be viewed as cognitive devices that can help policymakers with up to six analytical tasks:

Defining the nature of the situation confronting the decision-maker

Assessing what's at stake

Providing policy prescriptions

Predicting the chances of success of policy options

Evaluating the moral rightness of policy options

Warning about dangers associated with a policy option

I will use Khong’s framework to look at potential policy implications of all major AI analogies.

2.2 Analogies in legal decisions

There is often ambiguity how emerging technologies fit into a limited number of existing legal categories. Hence, the application of existing law to emerging technologies can turn into a “battle of analogies”:

Uber and Lyft as transportation vs. information services: Are ride-sharing companies more like transportation services or more like information services? The former have much stricter regulation than the latter (European Court of Justice, 2017).

Cryptocurrencies and financial regulations: Are cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin more like a currency (e.g., dollar), a commodity (e.g., gold) or a security (e.g., share in a company)? These analogies have been employed by regulatory bodies to determine how these digital assets should be regulated in terms of taxation, anti-money laundering laws, and investor protection.

AI as an author vs. tool: Is AI more like an author of text, pictures, or inventions or merely a tool used by a human creator? In cases like Thaler v. Iancu, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and subsequent judicial rulings have debated whether an AI system can legally be the owner of patents and copyright.

2.3 Analogies in the design of governance institutions

Analogies can also play a role in what new governance structures are considered for emerging technologies, such as in the current discussions around international institutions for AI governance.

“IAEA for AI”: The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and inhibit its use for military purposes. OpenAI and its CEO Sam Altman (2023) have repeatedly suggested this as a blueprint for a new international organization.

“CERN for AI”: The Conseil européen pour la recherche nucléaire (CERN) is an intergovernmental research organization that provides the particle accelerators and other infrastructure needed for high-energy physics research. Gary Marcus (2017), Sophie-Charlotte Fischer & Andreas Wenger (2019), and others have suggested it as a model for a collaborative, international research organization dedicated to advancing AI technology and science.

“IPCC for AI”: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides scientific assessments on climate change to guide global policy. Analogously, an "IPCC for AI" as suggested by Kohler, Oberholzer & Zahn (2019), Bak-Coleman et al. (2023), and Suleyman et al. (2023) would imply an international, scientific body that assesses and reports on the impacts of intelligence change.

3. How (not) to use analogies

Analogies play no central role in discussing narrow AI questions, such as the accuracy and bias of facial recognition systems. We can discuss these with numbers from evaluations. In contrast, in discussions of broader, more long-term questions AI researchers, tech CEOs and policymakers much more heavily rely on analogical reasoning. In short, analogies as mental heuristics are especially helpful to decision-makers in situations with high degrees of uncertainty or ambiguity. However, we also know that mental heuristics come with their own trappings.

Analogies are not substitutes for evidence or hard questions

Analogies can be misleading in multiple ways:

the analogized relationship A:B, often does not perfectly correspond to C:D,

we should be cautious about overfitting empirical data to preconceived notions,

claims that a specific set of relationships are analogous are often overgeneralized to a broader intuition that the source domain and the target domain are analogous in general, including in aspects in which they are not.

“If a satisfactory answer to a hard question is not found quickly, System 1 [the brain's fast, intuitive way of thinking] will find a related question that is easier and will answer it.” - Daniel Kahneman, 2011

In other words, we might be tempted to make a mental substitution of a hard question (“How should I think about policy options in the target domain C?”) with a simpler question (“What policy options have worked in the source domain A?”), without considering that these domains are also different in important aspects (A:B = C:D, but A:E ≠ C:F). Consequently, the consideration of a single analogy to address a complex question with high levels of uncertainty can result in overconfident and misguided judgement. For example, the isolated use of the most salient historical analogy means that “generals are always prepared to fight the last war”.

Analogies can help to explore and reduce uncertainty

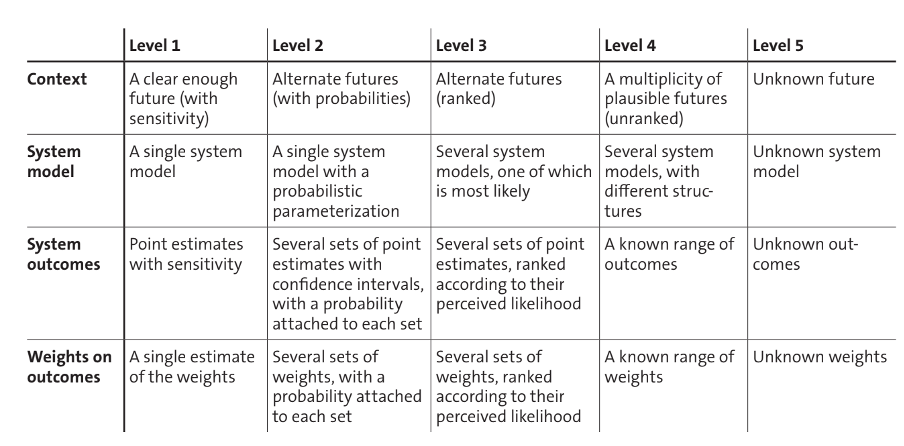

When we look at something broad and open-ended like the long-term impacts of AI from a governance perspective, we do not automatically start with a limited number of futures, scenarios, and policy options. Instead, we begin with no clear system model, it is not fully clear which domain logic is the most appropriate or what questions, scenarios, risks, or opportunities we should pay attention to. Analogies can be a tool to explore such a future with deep uncertainty.

Analogies can help to reduce uncertainty from “level 5” to “level 4”. Especially, if we consider multiple analogies, and if we actively search for and consider multiple and even contradictory parallels. Another way to illustrate the function of analogies is through the parable of the “blind men and the elephant” as a meta-analogy:

“A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form. Out of curiosity, they said: "We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable". So, they sought it out, and when they found it they groped about it. In the case of the first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said "This being is like a thick snake". For another one whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. As for another person, whose hand was upon its leg, said, the elephant is a pillar like a tree-trunk. The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, "is a wall". Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth and like a spear.”

Applied to our case, AI is the elephant, and we are the blind men. AI analogies that people use to describe the elephant capture some aspect of it. However, no analogy is perfect, and any specific analogy only applies to a specific set of relationships, not AI as a multidimensional phenomenon with diverse social, technological, economic, environmental, and political impacts.

So, the goal of this series is not to tell you which analogy is the right one. Nor is it to discourage the use of analogies. The goal is to consider multiple analogies and to be precise with regards to what specific aspects they apply to, and what aspects they don’t apply to. In this manner, analogies can hopefully help to slowly piece together a clearer picture of the shape of things to come.

4. On this project

I do think AI analogies are relevant enough that someone should spend a couple of days researching and thinking about them and work out some nuances. Not for every random analogy, but at least for the 20-25 most relevant ones. Realistically, a CEO of a tech firm or a leading AI researcher does not have unlimited time to reflect on the nuances of analogies that he or she likes to use as heuristics to think about the future of AI. However, a digestible 10-15 min summary per analogy can hopefully be a useful contribution to the AI discourse. So, that’s my plan.

Scout mindset: The goal is to “squeeze” the analogies for their full exploratory value, regardless of their relative popularity with different AI camps.

Openness to feedback and collaborators: It would be impossible to have deep domain expertise in the full range of source domains used for AI analogies and there is a trade-off between speed and comprehensiveness. As such, my analyses will inevitably still have flaws and gaps. If you have feedback, suggestions, or would like to collaborate don’t hesitate to reach out to kevin@kevinkohler.ch

Further readings:

Kevin Kohler. (2019). The Construction of Artificial Intelligence in the U.S. Political Expert Discourse.

Stephen Cave, Kanta Dihal, & Sarah Dillon. (2020) AI Narratives: A History of Imaginative Thinking about Intelligent Machines.

Lewis Ho et al. (2023). International Institutions for Advanced AI.

Jason Hausenloy, & Claire Dennis. (2023). Towards a UN Role in Governing Foundation Artificial Intelligence Models.

Matthijs Maas. (2023) AI is like…: A literature review of AI metaphors and why they matter for policy.