A universal basic income (UBI) is often presented as a public insurance against large-scale and potentially permanent technological unemployment. Many Silicon Valley leaders that believe in the transformative economic potential of artificial general intelligence (AGI) have also voiced their support for UBI (e.g. Sam Altman, Elon Musk).

UBI can be a part of the policy tools to address long-term technological unemployment. However, it is worth highlighting that a UBI to address long-term technological unemployment is more expensive than current UBI proposals and that it is not a sustainable solution to finance an insurance against widespread loss of labor income by taxing labor income:

A post-labor UBI is expensive because it would not merely supplement labor income, but fully replace it. Additionally, the more affordable alternative of a guaranteed minimum income would approach the cost of a regular UBI in a post-labor scenario.

To explore the challenge of financing a UBI in a scenario of large-scale technological unemployment we will examine the case study of Switzerland. The Swiss were the first worldwide to vote on a nationwide and fairly generous UBI in 2016.

In short, distributing money through a UBI can be a solution to a lack of labor income. However, the hard part is designing income streams that grow in lockstep with the parts of the economy that grow in a scenario of high automation and accordingly can finance a rising demand for UBI or other forms of social security.

1. UBI for technological unemployment is expensive

1.1 A guaranteed minimum income is cheaper than UBI, but would approach the cost of UBI in a post-labor economy

In the public discourse, the terms UBI and guaranteed minimum income are often used interchangeably. However, they denote different concepts and many famous “UBI proposals” and “UBI trials” are actually guaranteed minimum income proposals and trials. The main reason for this is that guaranteed minimum income is much cheaper to implement than a UBI. However, in a scenario of large-scale unemployment the costs of guaranteed minimum income would rise rapidly and approach the cost of a UBI.

Universal basic income

A UBI is commonly defined as having the following characteristics:

Periodic: a recurrent payment (e.g., every month)

Cash payment: paid in cash, allowing the recipients to convert their benefits into whatever they may like.

Universal: paid to all, independent of income, employment status, children, health status or other factors. Not targeted to the poorest or those who need it most.

Individual: paid on an individual basis (versus household-based).

Unconditional: involves no work requirement

In a UBI everyone actually receives a transfer payment. The idea is that making the payments universal increases buy-in for the program and reduces the stigma of needs-based benefits (“like a school uniform”).

A good example of a UBI proposal is the “Freedom Dividend”, the signature policy proposal of the 2020 Democratic primary candidate Andrew Yang. The proposal would give every US-citizen over the age of 18 1’000 USD per month per person.

Guaranteed minimum income

A guaranteed minimum income or negative income tax is the idea that the state will ensure that everyone reaches a minimum monthly or yearly income. If you don’t reach it, the state will pay the difference, otherwise you will not get anything. So, while the cash payments do not require any active action, payments are withdrawn as labor income rises.1

Good examples of guaranteed minimum income proposals are those put forward in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s by Milton Friedman, Richard Nixon, and George McGovern.

In a labor economy, a guaranteed minimum income is a lot cheaper to implement than a universal basic income of the same amount. However, this also means that the costs of a guaranteed minimum income program would rise rapidly in the case of technological mass unemployment as the number of beneficiaries expands. In contrast, the cost of a UBI remains the same regardless of the number of unemployed and underemployed.

1.2 A public spending-neutral UBI is not enough in a post-labor economy

Supporters of UBI like to point out that a remarkably heterogeneous coalition of thinkers including technologists, libertarians, and socialists support the idea of a UBI. However, as always, the devil lies in the details.

Thinkers on the left, such as Philippe Van Parijs & Yannick Vanderborght (2017), generally look at a relatively generous UBI as a foundation to build stronger and much more expansive welfare states. In contrast, libertarian thinkers, such as Charles Murray (2006), are more interested in a public spending-neutral UBI. In other words a UBI that is entirely financed by replacing existing welfare spending.

a) A public spending-neutral UBI would reduce income for some low income households

A spending-neutral UBI reform financed by cutting a large fraction of existing social security programs would increase the amount of beneficiaries that receive a share of social security spending (everyone) at the expense of lower spending per beneficiary. Meaning, it would generate more winners than losers among the population. However, the average loser loses more than the average winners gains. In most countries the current allocation of social assistance programs is more effective in reducing poverty than a spending-neutral UBI reform.2

Under spending-neutrality the UBI would have to be set considerably below national poverty lines. According to the OECD, a budget-neutral UBI would amount to €158 per month per adult in Italy, £230 in the United Kingdom, €456 in France, and €527 in Finland.

b) A UBI large enough to maintain or increase transfers to all low-income households would be very expensive

Financing a UBI at 100 per cent of the national poverty line for adults and 50 per cent to children up to 15 years old, would cost between 20 and 30 per cent of GDP in middle income and high income countries and 50 per cent or more in low income countries (graph below).

c) In a post-labor economy we would optimally have a universal high income

A universal basic income should be enough to live on, but just barely. The exact amount differs based on regional income and purchasing power levels. However, most proposals are set below and at best at the local poverty line. The idea is that you have peace of mind if you need to leave an abusive partner, a toxic job, look after a child or try to pursue self-employment. However, you should still be incentivized to seek employment again.

In contrast, if the premise is a persistent problem of technological employment that renders a significant share of the population “unemployable” then a basic income is not exactly utopia. It would ensure that no one starves but it would essentially create a permanent underclass. Hence, some, such as Elon Musk, hope that a growing machine economy will enable a “universal high income”, where humans can comfortably live indefinitely without having to work.

Today, most “UBI” trials use some mechanism to select participants with low income and are closer to a guaranteed minimum income. They are tested as an alternative to other forms of social security or as a supplemental income to low-income households. Hence, they may find that people receiving a UBI have improved well-being. Who wants to run the experiment measuring the well-being effects of replacing the salary of programmers with a 1’000 USD a month UBI?

2. Financing a UBI by taxing labor is not “post-labor proof”

Let’s look at the Swiss popular initiative “For an unconditional basic income”, which was submitted in 2013 and rejected by voters in 2016. The initiators have proposed3 that all permanent resident adults should receive 2’500 CHF (ca. 2950 USD) per month and all children and young people 625 CHF (ca. 730 USD) per month. These numbers were also used in an accompanying volume of essays published by supporters of the initiative and the government has used these numbers as the basis for official calculations presented in the official voting material.

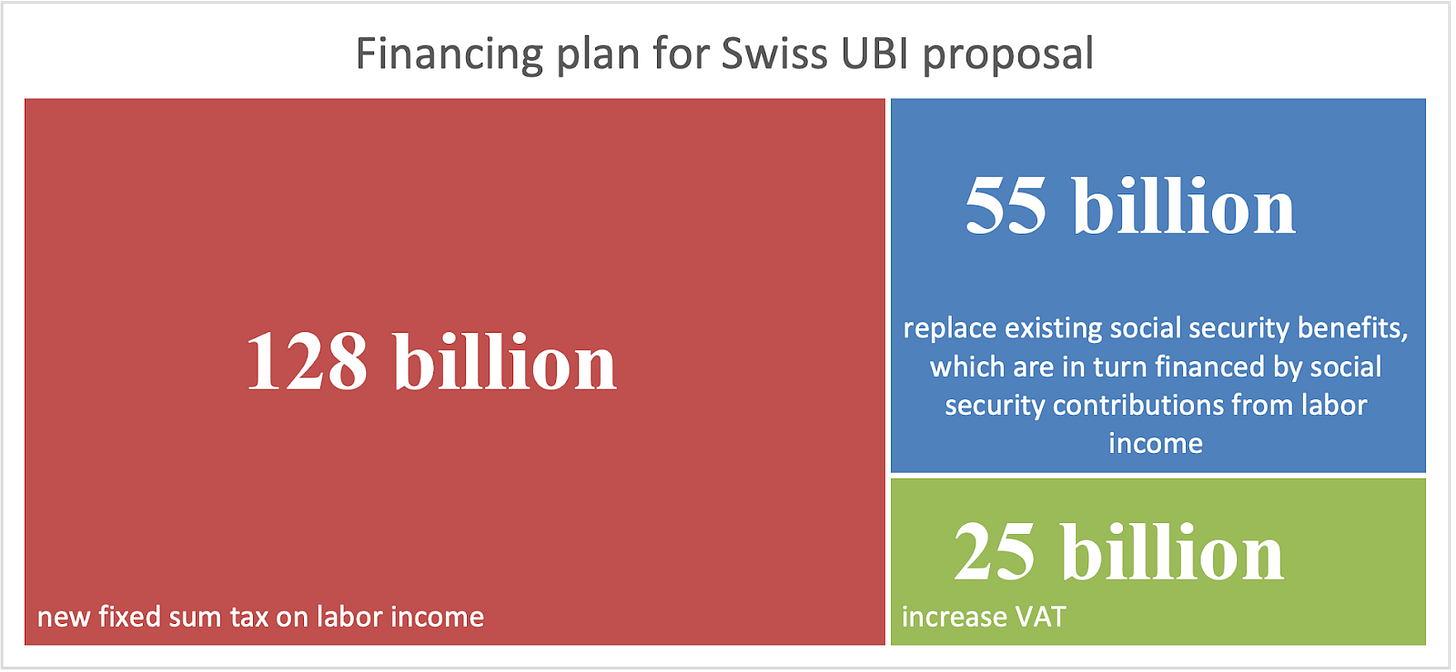

Specifically, the government calculated that the proposed universal basic income would cost about 208 billion CHF annually (ca. 30% of GDP) to cover 6.5 million adults and around 1.5 million children and young people.4 In discussions with the initiators, the government calculated that the basic income would replace many existing social security benefits, the corresponding savings could finance around 55 billion. Still, social security spending would have to be nearly quadrupled and an additional 153 billion would be required. Around 128 billion CHF of this could be covered by deducting 2’500 CHF from every earned income, or the entire income for incomes below 2’500 CHF.5 The remaining gap of 25 billion CHF or so would have to be financed by significant savings or tax increases. For example, the VAT could be doubled from 8 to 16 per cent.

So, what’s the issue?

2.1 We don’t know how soon we may run out jobs

A further expansion of the welfare state without significant automation may be premature. Many advanced economies face rapidly ageing societies with worsening dependency ratios and historically high levels of public debt.

We also know that there have been previous waves of automation anxiety that ultimately turned out to be false alarms. Supporters of the initiative held a “robots for UBI” protest and stressed the progress of automation: “Robots are doing more and more work. It is now our task to shape society in such a way that everyone has a dignified life thanks to the digital revolution: More meaningful and self-determined activities are possible.”6 And yet, here we are another 7 years later: We still haven’t even managed to automate trains and many Western economies have labor and skills shortages. Given this context, we may want to scale a UBI incrementally, in lockstep with the expansion of the AI economy.

2.2 Most financing of the Swiss UBI would fall away in a post-labor scenario

Let’s make an extremized thought experiment and assume that AI will replace all human jobs within the next 10 years. Nearly two-thirds of the foreseen funding for the UBI came from labor income tax. If labor becomes obsolete there is suddenly a 128 billion CHF funding gap. On top of that, labor income taxes also form the backbone of the general government budget of Switzerland and most other developed nations. Across the member states of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), about 50% of all tax revenues in 2023 came from individual income taxes and social security contributions.

In short, as the Genevan law professor Xavier Oberson argued: “Should mass workplaces for humans disappear in the future, from a tax perspective a double negative effect could occur. On the one hand, significant tax and social security revenues would be lost, while on the other hand, the need would increase for additional state revenue to support the growing number of unemployed human workers.”

Solutions

What is needed to address both the timing uncertainty and the long-term financing issue of UBI with regards to the prospect of technological unemployment is a financing mechanism that scales with the growth of the machine economy. We will explore the strengths and weaknesses of some of the more popular suggestions to address this - from a windfall clause, to a robot tax, to a sovereign wealth fund, to broader stock ownership, to international tax reform - in upcoming posts.

Thanks to

and for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay. All opinions and mistakes are mine.This can be based on monthly or annual income checks and with corresponding phaseout provisions. In the extreme case, this can mean that participants have up to 100% marginal tax rate for earning additional income through labor until they reach the minimum income. However, something like 50% phase-out is more common. As

has explained, a 100% marginal tax rate reduces willingness to work and hence this is not the best design in the current system.Ugo Gentilini, Margaret Grosh, Jamele Rigolini, & Ruslan Yemtsov. (2020). Universal Basic Income: A Guide to Navigating Concepts, Evidence, and Practices. worldbank.org p. 133

Strictly speaking the text on which the Swiss voted did not specify how high the UBI would be, how it would be financed and who exactly exactly would be entitled to it. In some sense, one can view this as strategic ambiguity to get buy-in from more socialist and more libertarian UBI supporters.

Swiss Federal Council. (2016). Volksabstimmung vom 5. Juni 2016: Erläuterungen des Bundesrates. pp. 14&15

This financing mechanism means that even though the Swiss proposal is a UBI in which everyone receives an actual transfer, it would have had the characteristics of a guaranteed minimum income with a 100% marginal tax rate on labor income from 0 to 2’500 CHF.

Swiss Federal Council. (2016). Volksabstimmung vom 5. Juni 2016: Erläuterungen des Bundesrates. p. 19

Great piece Kevin illustrating again that 1) UBI is a broad term with different meaning for different people. 2) The mathematics make the cost very difficult to justify in the AGI context.

I have a couple of pieces I am working on that discuss this. First, historically, automation has created more jobs than it destroyed. Given this, we could argue that fears of AI mass unemployment are overblown.

On the other hand, if AI does offer a “better than human” stand in for labor and cognitive tasks (assuming AI is also controllable) then the explosion of ideas creation will lead to incredible economic growth while also potentially driving down the value of human labor.

Both scenarios have positives, the former doesn’t require UBI, the latter creates incredible wealth where it might make UBI possible.

For me, the solution then is to begin replacing welfare programs with cash benefits now. That way, depending on which future path turns out to be correct, we can simply adjust the amount of cash distributed over time.

honestly i'm surprised i've never heard UBI framed this way until now.there's a leap here that funding for UBI would come from an income tax, which i'm not wholly sold on. technology is deflationary, or such is the trope, and to what degree you accept that as accurate would seem to drive a lot of how you think about "post-labor" economy.

because if technology _is_ deflationary -- if technological growth decreases the costs of production -- then the real cost to providing the "base necessities" ought also to decrease in time, absent shifting definitions for what those "base necessities" are. "post labor" in the *extreme* means that labor is completely absent from production: that all production is automated. then where is the scarcity? where do you point and say "*this* is why the products of a post-labor economy have a cost to them (and hence, are inaccessible to those without means)"?

taking "post-labor" seriously, then ask "if it requires no labor to manifest a factory which would provide all the material food, shelter, and basic needs, then what's preventing each person without other means from doing so?". the intuitive answer is "actually it _does_ still require labor to do those things, it just isn't legible". but that's just a denial of "post labor", and the question should shift to focusing on that failure to allocate labor.

the answers to the above which accept "post labor" have to confront that the constraints on production *no longer have to do with the differences between individuals*. they're things like "you can't manifest a factory here because someone else owns the land required for it", or "someone else owns the patents", and other such things where you're dealing with property rights which were at best obtained during a period _before_ this "post-labor" economy.

perhaps a practical answer to the above is that even in a post-labor economy, there are inescapable physical constraints. there's still a limited supply of the material inputs to such an economy: the different ores needing to be mined from the earth, energy inputs from the Sun, and so forth. if a UBI exists in such an economy which fully automates production downstream of those physical inputs, a price system serves to allocate those physical inputs, indirectly, to the people downstream of all this. it doesn't require taxation of any kind. it's just a recognition that if we didn't enforce a price system, those material inputs would be allocated wastefully. and i'm not sure what more palatable form of allocation would exist there other than "everyone gets a roughly equal share of the inputs, which we distribute by means of some UBI".

anyway, i don't expect this conclusion to be met with cheers. but i'm not sure how to avoid it except by claiming that post-labor is a lie, or that increased unemployment isn't wholly technological (which to be honest, is far more believable to me).