IPCC for AI: An overview

“I hope that we can go as far as creating an IPCC for artificial intelligence, in other words, truly creating an independent global expert body that can measure and organize the collective and democratic debate on scientific developments in a totally independent way (...) it it is up to governments and public authorities to invest in this area and to guarantee the global framework of this independence through this IPCC for artificial intelligence.” - Emmanuel Macron, 20181

This post examines the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as an analogy for similar scientific assessment bodies focused on AI.

The first section provides a short background on the IPCC.

The second section provides overview tables of “IPCC for AI” proposals and of ongoing projects to track, monitor, and measure AI.

The third section discussed a number of considerations when designing an “IPCC for AI”.

1. A brief introduction to the IPCC

1.1 Mandate

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an independent scientific advisory body founded in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the UN Environmental Programme and endorsed by the UN General Assembly.

The mandate of the IPCC is to “assess on a comprehensive, objective, open and transparent basis the scientific, technical and socio-economic information relevant to understanding the scientific basis of risk of human-induced climate change, its potential impacts and options for adaptation and mitigation.”2 The IPCC produces comprehensive Assessment Reports approximately every five years. These reports synthesize existing scientific literature on climate change rather than conducting original research. However, the IPCC can indirectly stimulate research as its reports contain sections on limitations and research gaps, and the announcement of a special report can catalyze research activity in that area.

1.2 Organization

Working groups: The assessment process is carried out by scientists in three working groups:

Working Group I - Physical Science Basis of Climate Change

Working Group II - Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability

Working Group III - Mitigation

Each working group produces a report with more than 1’000 pages, and a summary for policymakers of approximately 30 pages. The scientists are selected from a pool of nominations from member governments and observer organizations based on relevant scientific expertise and to some degree demographic representativeness.

Plenary: The Plenary is the main decision-making body of the IPCC and consists of political representatives of UN member states. It is responsible for:

Approving major reports, including the line-by-line approval of the Summary for Policymakers.

Electing the IPCC Chair, Vice-Chairs, and Bureau members.

Setting the scope, outline, and work plan for assessment cycles.

The IPCC allows non-profit organizations with relevant work on topics related to climate change (e.g., civil society, academic institutions, private sector associations, international organizations) as observers. However, as its name indicates, the IPCC is an intergovernmental body, not a multistakeholder body. Only countries can vote.

1.3 Consensus

The IPCC assessment reports strive to reflect a scientific consensus opinion.3 Rather than going by majority voting, or qualified majority voting, the IPCC usually aims for unanimity, meaning every country can veto a specific passage. This approach has solidified the consensus that climate change is anthropogenic and fostered the development of a transnational epistemic community of scientists.

However, this focus on consensus means that the IPCC tends to avoid highly contentious issues. For instance, some critics argue that the IPCC does not adequately address the uncertainty around climate tipping points and climate sensitivity, which remain areas of significant scientific debate.

1.4 Link to international climate treaties

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) conducts policy-relevant but not policy-prescriptive assessments of climate science. Meaning, it does not make any policy recommendations. The first assessment report of the IPCC, published in 1990, provided the scientific basis for the negotiation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) at the 1992 ‘Earth Summit’ in Rio de Janeiro. The UNFCCC has since negotiated key international treaties on climate change, including the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Paris Agreement (2015).

Although the IPCC operates independently from the UNFCCC, the two organizations are often seen as "siblings" that have grown together and collaborated closely. The international participation facilitated by the IPCC has fostered consensus and familiarized policymakers with climate science, making the establishment of climate conventions more feasible.

1.5 IPCC analogy for biodiversity

The IPCC is widely regarded as a successful model of the science-policy interface and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. This success has inspired4 the creation of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2012. However, while the IPCC focuses on aggregating and assessing knowledge on climate change, the IPBES has a broader mandate that includes increasing the knowledge base, building capacity, and providing policy support due to the larger existing knowledge gaps in biodiversity and ecosystem services.

2. “IPCC for AI” proposals

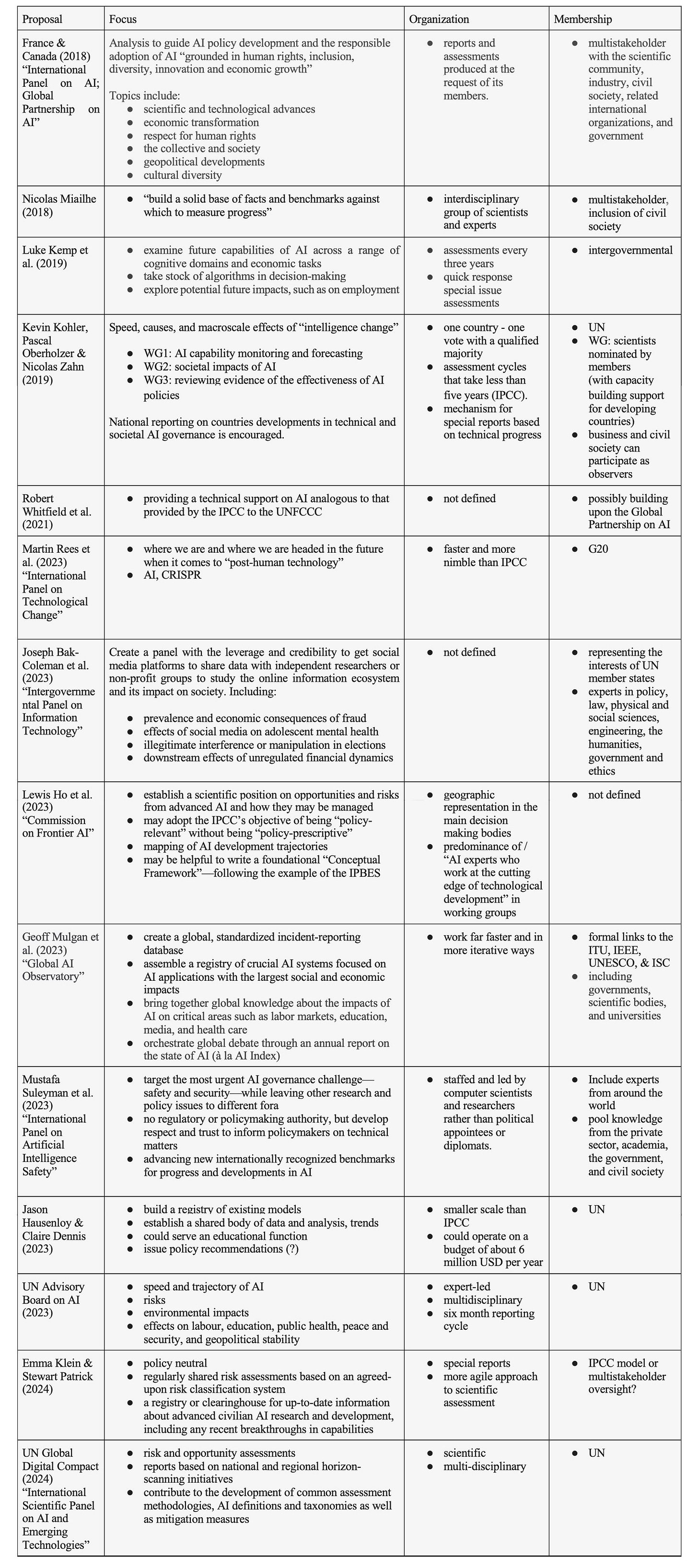

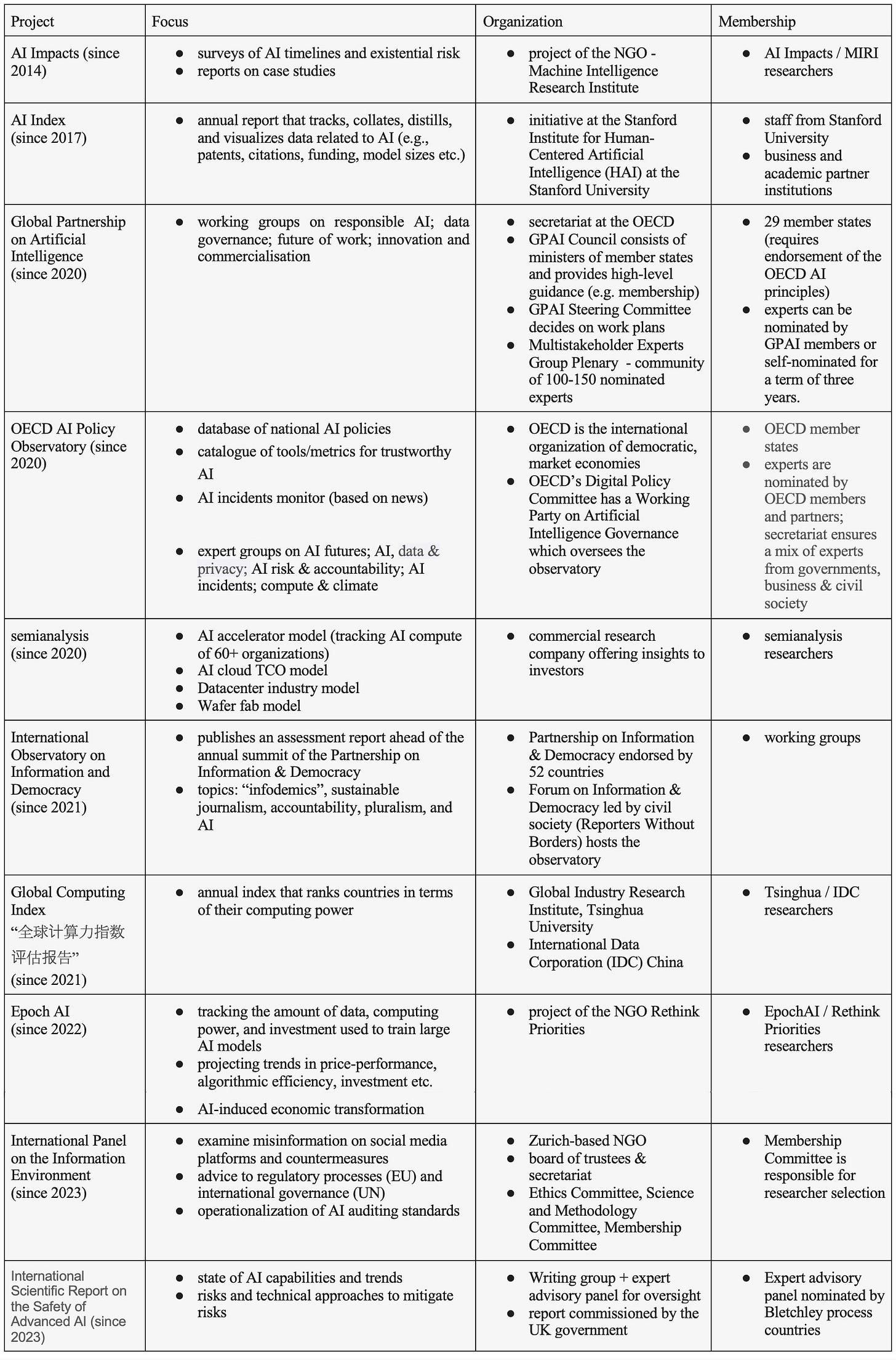

The following is an overview table that outlines the suggested focus, organization, and membership of 14 proposals for an “IPCC for AI”. Mentions of support for an “IPCC for AI” without additional explanation in an op-ed or report (e.g., WEF Global Risks Report 2023, Ursula von der Leyen (2023)) have not been included. Matthijs Maas & José Jaime Villalobos (2023) also offer an overview of IPCC for AI proposals.

Additional contexts, sources, and quotes for the listed proposals can be found in the Annex. Aside from proposals, there are also four existing projects that were in part inspired by the IPCC analogy (Global Partnership on AI, International Observatory on Information and Democracy, International Panel on the Information Environment, International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI). The table also lists six additional projects that have not explicitly used this analogy, but that fulfill some functions that align or overlap with some “IPCC for AI” proposals.

To limit the complexity, we can mentally categorize the “IPCC for AI” proposals into three main tracks:

2.1 The Global Partnership on AI

The first cluster of proposals starts with the French President Emmanuel Macron, who worked with the Canadian government to create an “IPCC for AI”. This process eventually led to the Global Partnership on AI. The proposals from Miailhe, Kemp et al., Kohler et al., and Whitfield et al. were all at least in part prompted by the French-Canadian proposal. While the authors were usually supportive, some have argued that global legitimacy like the IPCC can only be achieved by bringing the process to the UN.

2.2 The Bletchley Process

The increased salience of AI governance post-ChatGPT and the UK announcement to host an international summit on AI safety has opened a window for new international institutions for AI. The Suleyman et al. proposal was written in anticipation of the UK AI Safety Summit and the International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI is the IPCC-effort of the Bletchley process.

2.3 The UN Process

Lastly, it looks as though the UN will now most likely launch an “IPCC for AI” process. This cluster includes the report of Hausenloy & Dennis for the UN University, the interim recommendations from the UN Advisory Board on AI that advises on the Global Digital Compact, as well as the draft of the Global Digital Compact, which is one of the main deliverables for the UN Summit of the Future in September 2024.

Aside from these three international tracks, there are two more notable clusters:

OpenPhilantropy: AI Impacts, AI Index and Epoch AI are three non-profit efforts to track and anticipate AI developments that are supported by donations, with Open Philanthropy being a prominent supporter of all of them. This cluster has not explicitly used the “IPCC for AI” analogy, and has no aspiration to be intergovernmental. However, in practice they are heavily referenced in the AI discussion, albeit with slightly different focus points (surveys, benchmarks, compute tracking and trajectories).

Online information environment: The International Observatory on Information and Democracy, the International Panel on the Information Environment and the counter-proposal by Joseph Bak-Coleman et al. in Nature all belong in this category. The primary focus is on social media and AI mainly comes into play due to concerns about AI-generated misinformation and disinformation.

3. Considerations

Key differences between the contexts of climate change and AI include scientific consensus, system-orientation, “wizard” vs. “prophet” long-term vision, considered time horizons and speed of change. These are discussed separately in “Intelligence change vs. climate change”.

The following are eight more specific factors and questions that are worth considering when designing and implementing an “IPCC for AI”.

3.1 Reporting intervals

Many “IPCC for AI” proposals explicitly mention the high speed of change in AI. This would arguably require faster and more flexible assessment cycles than the 5-8 years intervals between climate assessment reports. For example, the Bletchley Process foresees a major meeting every 6 months, and the UN Advisory Board on AI has suggested a similar pace for UN assessment reports.

Similarly, the process from the founding of the IPCC (1988) to Paris Agreement (2015) took 27 years. Hence, if the “IPCC for AI” is meant as a stepping stone towards a global treaty that process would most likely have to be accelerated as well.

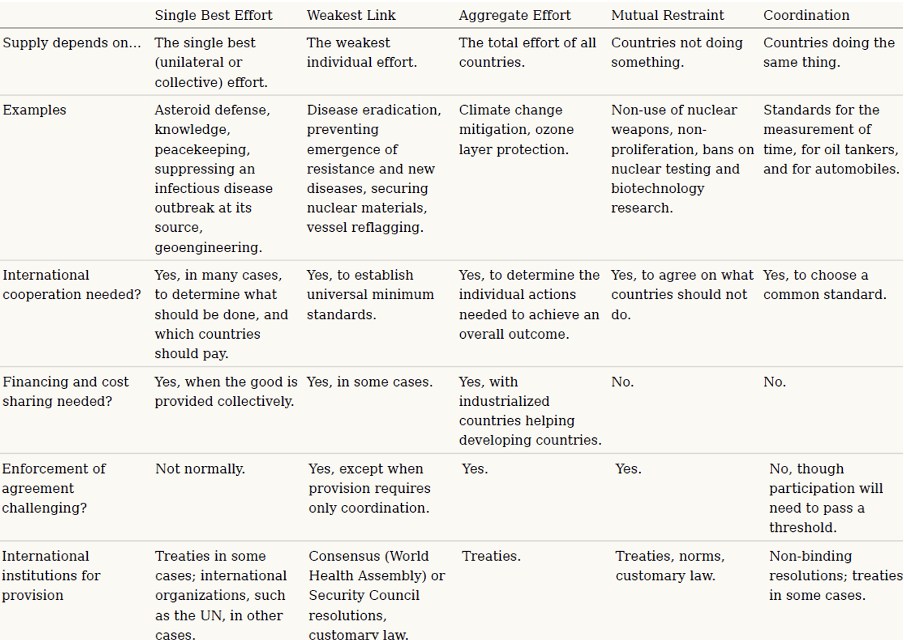

3.2 Single-Best Effort Global Public Good

IPCC: The IPCC assessment reports are public goods. They are available to anyone free of charge and the consumption of them is non-rivalrous. More specifically, they are a single-best effort global public good.

In other words, this is a public good at the global scale and its provision is more or less determined by the quality of the single best available report. Imagine for a moment that dozens of nations, businesses, and universities would operate their own autonomous projects to synthesize the scientific literature on climate change and project its trajectory. How many assessments of the same global phenomena would you bother to read? How much added value would the 10th best assessment or the 100th best assessment create?

AI: A public “IPCC for AI” assessment that summarizes the global state and long-term trajectory of AI would fall into the same “single-best effort global public good” category, at least theoretically. So, why is there a steady stream of novel suggestions for global AI assessments?

Arguably, no project has developed the legitimacy and gravitational pull yet to become the clear leader. The Global Partnership on AI assessments have not been able to match the original aspiration of a global systemic assessment like the IPCC reports. In practice, they largely focus on discussing specific sectoral and local developments and impacts without a global overview with data-based, tracking and projections of global installed AI capacity and similar global indicators.

That a global assessment of AI nevertheless can have “single-best effort” characteristics can be seen where an organization performs one element of it exceptionally well. For example, Epoch AI has established itself as the clear leader in monitoring and projecting the computing power used to train notable AI models. Hence, other organizations like AI Index or the International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI don’t bother using the same and instead re-use its data.

The question going forward is how to avoid too much “IPCC for AI” duplication. One very good and legitimate effort would arguably be better than spreading the same scientific resources across three good efforts with a lot of duplication. Hence, the idea that the Bletchley track and the UN track could be merged or made more complementary in some way seems reasonable. For example, the Bletchley process could become the safety/security working group of the UN track. Or, if the UN track cannot match the 6 month speed of the Bletchley process, the Bletchley process could be the faster but more informal assessment that works closely together with a slower, more politically legitimated UN report.

3.3 Global legitimacy

IPCC: The UN provides the IPCC with global legitimacy. At the same time, as in most scientific fora, it is to be expected that developed countries are represented in higher numbers than developing countries, because they conduct more science. In the IPCC, input legitimacy was strengthened through affirmative multilateralism, meaning travel grants as well as training to build up the capacities of smaller economies, which made up about half of the early IPCC budget. This has ensured that a broader and broader set of countries has participated in the process over time.

AI: A key advantage of an UN-based “IPCC for AI'' would be its global legitimacy. However, at the same time, AI expertise is not distributed equally (see e.g., scientific publications, funding) and not all countries will be interested or have the capacity to participate in such a panel from the beginning.

Smaller and developing countries have limited means to follow decentralized, complicated discussions and prefer centralized focal points and helpdesks. To bolster legitimacy and to get buy-in from such states, some type of travel grant and capacity building program may be useful.

3.4 Is there a key indicator?

IPCC: The tracking of anthropogenic global warming famously started with the Keeling curve, which showed the rising levels of atmospheric CO2. Atmospheric CO2 has seasonal variation (lower in summer due to plants) but is close to universal.

The long-term goal of climate policy is the rise in global mean average temperature from pre-industrial levels.5 This again frames climate change as a single global challenge and it is more legible to the broader public than greenhouse gas concentrations.

Counterfactually, a framing focused on not reaching specific climate tipping points (e.g. arctic ice sheet), on global sea level rise, on the amount of extreme heat days or on the overall losses from climate-related natural disasters, might have put more emphasis on the differences in vulnerability to climate change.

Framings can also link risks and opportunities to different degrees, and predispose individuals to specific solutions. For example, a framing around energy would highlight both risks and opportunities of fossil fuels, whereas climate assessments naturally focus on their contribution to risks.

AI: The closest-equivalent to the Keeling curve in AI are graphs of the price/performance of chips, graphs of the computing power of supercomputers, or graphs of the computing power used to train large AI models. All of these are evidence of intelligence change. However, these are also all artifact-level indicators, they are not global systemic indicators.

Furthermore, the risk and opportunities are conceptually much more linked for intelligence than for energy. There is no agreement on any indicator that would specifically track undesired negative externalities of intelligence.

3.5 Reporting duty vs. pro-active data collection

IPCC: The IPCC synthesizes available data and published scientific literature from multiple sources. Countries have no reporting duty to the IPCC. However, the IPCC helps to define common guidelines for how to report national greenhouse gas emissions.

As part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) countries are required to submit their greenhouse gas emissions and removals of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)) from five sectors (energy; industry; agriculture; land-use change and forestry; and waste). However, the verification regime is weak and it is a dual-regime, with much less stringent reporting requirements for “developing countries” (incl. China).

AI: Something like an international KYC-regime with tiered reporting requirements for companies when they use large amounts of AI computing power can make sense. However, this is probably better tied to national oversight and regulatory agencies. A potential reporting requirement to a global network of scientists might raise concerns about privacy and espionage, and it might not be that relevant for an “IPCC for AI” with a systemwide focus.

First, a team that pro-actively collects country-level data from publicly available sources and creates its own projections using consistent methodologies can often outperform mandatory national reporting schemes in accuracy and reliability. For example, the push for the national reporting of disaster losses to the UN has been a mixed success so far.

Challenges that any effort of national reporting to an international body will face include:

Incomplete reporting: International reporting is often not a high priority for governments. Some countries may report with significant delay, others will fail to report at all.

Inconsistent methodologies: Different countries and agencies may use different methodologies for data collection and reporting, leading to inconsistencies that hinder accurate comparisons and analyses.

Incentives to misreport: National entities may have political, economic, or social incentives to underreport or overreport certain metrics.

Hence, if we take the example of disaster losses again. In practice, the official Sendai Monitor to track global disaster losses has not managed to replace the much smaller and leaner effort from a Belgian university as the standard source of disaster loss data.

Second, the supply chain of AI is concentrated with some very specific bottlenecks. Hence, even if there would be some reporting requirement to track global AI capacity, the easiest way to implement this would not be through states but through the handful of companies at those bottlenecks.

3.6 Knowledge synthesis vs. knowledge creation

IPCC: As discussed, the IPCC only synthesizes the existing scientific literature.

AI: There is much less existing scientific literature on the science of intelligence change. Hence, as it has been the case for biodiversity and the IPBES, to what degree an “IPCC for AI” should also have original research and knowledge creation within its mandate.

3.7 Types of stakeholders

Multistakeholder vs. intergovernmental

IPCC: The IPCC is an intergovernmental body with multistakeholder aspects. It gives weight to academia and to a lesser degree to civil society in the assessment. However, the voting power is restricted to governments.

AI: Some proposals argue that an “IPCC for AI” should more or less follow the actual IPCC and IPBES model. Others have argued that the “IPCC for AI” should be a multistakeholder body. As Emma Klein & Stewart Patrick correctly highlight, these proposals are not explicit about whether this just pertains to involvement in the assessment or also in the oversight body, and none of them offers a concrete model for a multistakeholder oversight body.

The problem that any multistakeholder body faces is that there is essentially an unlimited potential supply of NGOs and businesses. If there is no limit to participation you can win votes by sending inflated numbers of organizations. Potential models include a fixed amount of representatives per sector per country (e.g., tripartite model - ILO), a true multistakeholder body for exchange that has little collective decision-making ability (e.g., Internet Governance Forum) or getting a small group of insiders to act as the appointed gatekeepers.

Business involvement

IPCC: The majority of IPCC authors work for universities, some work for government departments, and some work for NGOs or international organizations. They are not employed by coal or oil companies, which would be perceived as a serious conflict of interest. Similarly, only non-profits are allowed as observer organizations.

AI: The private sector is more directly involved in some of the assessments of the state and trajectory of AI. For example, the AI Index is co-directed by Jack Clark from Anthropic, it has corporate sponsors, such as Google and OpenAI, and corporate analytics partners, such as McKinsey and Accenture. About 20% of the experts of the OECD AI Policy Observatory are business representatives.

3.8 Who has the right expertise?

Selecting the right experts is what makes or breaks a global AI assessment. However, this task seems to be much more challenging for AI than for climate change.

Expertise fractionation

Observers and experts can find it challenging to determine the boundaries of expertise, meaning professionals may sometimes be called upon to make judgments in areas in which they have no real skill. For example, the professional ability to play football is not the same as the ability to forecast the results of football games, let alone the longer-term commercial development of the industry.

IPCC: Climate science is its own field of science studying the Earth’s climate. Climate scientists use mathematical models to simulate the climate system and predict future climate scenarios based on different greenhouse gas emission trajectories.

AI: Modeling intelligence change is not an established scientific field (yet). A fairly common method of estimating the long-term capabilities, economic impact, and risks of AI are perception surveys of experts in training AI systems. However, while AI experts naturally have better insight into the near-future based on what is being worked on in the labs, there is no evidence that AI experts are particularly good at anticipating the long term trajectory of AI correctly.

Tech stack layers

AI: An “IPCC for AI” should understand the long-term trajectory and impacts of AI so it seems intuitive that it would heavily or almost exclusively focus on “computer scientists” and “AI experts who work at the cutting edge of technological development”.

There is certainly a need for them. However, first it is worth pointing out that long-term AI forecasting tends to strongly rely on computing power (see e.g., Kurzweil, Cotra, Aschenbrenner). Due to the long planning cycles and large investment requirements the lower layers of the tech stack are much more predictable than pure algorithmic innovations. Yet, to project that capability you don’t need expertise in training AI models as much as expertise in the trajectory of AI chip manufacturing equipment, AI chips, and AI clouds. Second, if we talk about societal impacts, there are many disciplines beyond those building the technical artifacts that have relevant expertise (e.g. economists).

Credentials

AI: To boost legitimacy there is a need for prestigious experts on the panel. At the same time, an effective “IPCC for AI” would likely have to be fast and to be able to pro-actively collect and visualize public information across tech stack layers. This is in some aspects closer to OSINT than to academic publishing. So, expert selection should also take into account non-academic experience. If I would be able to freely design an “IPCC for AI” for maximum expected impact, I would bet on groups like Max Roser & co. (OurWorldInData), Jaime Sevilla & co. (Epoch AI) and Dylan Patel & co. (semianalysis).

Annex A - List of proposals for a “IPCC for AI”

A.1 France & Canada (2018)

In March 2018 Macron first mentioned the idea of an “IPCC for AI” in a speech in the context of the launch of the Villani report / french AI strategy.

At the G7 summit in Canada in June 2018, member states agreed to a high-level statement to “facilitate multistakeholder dialogue on how to advance AI innovation to increase trust and adoption and to inform future policy discussions”. The separate Canada-France Statement on Artificial Intelligence is much more explicit: “To this end, we are calling for the creation of an international study group that can become a global point of reference for understanding and sharing research results on artificial intelligence issues and best practices. This initiative will work to create internationally recognized expertise and provide a mechanism for sharing multidisciplinary analysis, foresight and coordination capabilities in the area of artificial intelligence that is inclusive and multistakeholder in its approach.”

In November 2018 Macron reiterated the idea of an “IPCC for AI” in his speech to the Internet Governance Forum:

“During the G7 Presidency in 2019, regarding artificial intelligence, building on the work conducted in recent months with our Canadian partners and the commitment that I made with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, I will spearhead the project to create an equivalent of the renowned IPCC for artificial intelligence. (...) I believe this “IPCC” should have a large scope. It should naturally work with civil society, top scientists, all the innovators here today. It should count on the full support of the OECD to better monitor this work, particularly when it comes to innovation. It should count on the full support of UNESCO regarding ethical questions (...)”

In December 2018 France and Canada published a mandate for an International Panel on AI

In May 2019, the idea was discussed by the G7 Digital Technology ministers and received support from all of the G7 except the United States (under the Trump administration).

At the G7 Summit in France in August 2019, Macron framed it as a Global Partnership on AI that will be set-up within the OECD.

In October 2019, Macron framed the Global Partnership on AI as an OECD centered institution, that is open to non-OECD members and whose goal is to foster an ethical consensus around questions such as facial recognition.

In June 2020, the Global Partnership on AI was launched with 15 initial member states.

A.2 Nicolas Miailhe (2018)

Miailhe is the co-founder of Paris-based AI governance think tank “The Future Society”. His December 2018 op-ed on the United Nations University website can be seen largely as a supportive statement in favor of the French-Canadian proposal.

“Given the high systemic complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity surrounding the rise of AI, its dynamics and its consequences – a context similar to climate change – creating an IPCC for AI, or ‘IPAI’ can help build a solid base of facts and benchmarks against which to measure progress.” - Nicolas Miailhe, 2018

A.3 Luke Kemp et al. (2019)

This is a feedback submission from February 2019 to the UN High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation from policy and existential risk researchers at Cambridge and Oxford. The feedback makes three recommendations, one of which is to consider an expansion of the French-Canadian proposal of an IPCC for AI.

A.4 Kevin Kohler, Pascal Oberholzer & Nicolas Zahn (2019)

foraus is a grassroots think tank for Swiss foreign policy. In October 2019, as part of our deliberations on AI and Swiss foreign policy we published the report “Making Sense of Artificial Intelligence: Why Switzerland Should Support a Scientific UN Panel to Assess the Rise of AI” aiming to provide our vision for an IPCC-like institution for AI (and arguing that Switzerland - who hosts the IPCC secretariat - should try to host it). Some key take-aways in which our proposal differs from GPAI:

United Nations: In order to not just be another report, but to have global legitimacy and to potentially help to set the scene for future global agreements, an “IPCC for AI” should be tied to the United Nations and open to all UN member states (like the IPCC and IPBES).

Intergovernmental vs. multistakeholder: While we agree that all stakeholder types are important, we think the IPCC-model where non-states can be observers, submit materials and nominate qualified experts for working groups, but not vote makes most sense. “Pure” multistakeholder bodies in which all participating organizations have equal status (à la Internet Governance Forum) can be great venues for discussions, but without a gatekeeper they tend to be limited as collective decision-making bodies.

Long-term vision: For questions of ambiguity and ethical values, we think there should be a more open, participative consultation that is not limited to a small set of experts. We also highlight that there is a flurry of ethical principles but no “grand strategy”, no agreement on a long-term goal (equivalent to the long-term temperature goal of the Paris agreement).

We also highlighted some ways in which we think an “IPCC for AI” should differ from the original IPCC:

Speed: We highlight that AI has a higher rate of change than climate change and that we should therefore consider faster and more flexible assessment cycles.

Consensus: Given the significant disagreements between some AI scientists, we do think that a very high bar for consensus might be counterproductive in that it leads to “lowest common denominator” statements and avoids some of the most important questions. Instead, we suggest qualified majority voting and explicitly listing remaining disagreements in reports.

We presented the report in 2019 at an event in Geneva with Amandeep Singh Gill (since 2022 - UN Technology Envoy).

A.5 Robert Whitfield et al. (2021)

A 2021 report on global AI governance published by the Transnational Working Group on AI and Disruptive Technologies of the World Federalist Movement and Institute for Global Policy.

The report recommends working towards an UN Framework Convention on AI analogous to the UNFCCC. As a stepping stone, the report recommends an “IPCC for AI”, highlighting that current efforts of the Global Partnership on AI could either be extended or a new effort could be created.

A.6 Martin Rees et al. (2023)

This brief op-ed in March 2023 from Martin Rees, Shivaji Sondhi, and Vijay Raghavanin in the Hindustan Times argues that the G20 should set up an International Panel on Technological Change that observes post-human technologies, such as superintelligence and CRISPR. The op-ed was timed ahead of the G20 New Delhi summit. I could not identify a clear link to a more comprehensive report or a specific process within the G20, however, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, explicitly mentioned the idea of an “IPCC for AI” at the G20 Summit.

A.7 Joseph Bak-Coleman et al. (2023)

In a comment in Nature in May 2023 a group of researchers of the societal impacts of digital information technologies called for an IPCC-like body to study the online information environment. In contrast to other proposals that primarily highlight computer scientists and AI researchers, this proposal focuses more on social scientists and researchers that might be interested in misinformation around public health or climate change.

The authors highlight that it has become more difficult for them as researchers to get access to data from social media platforms and that an international body would have more leverage in this regard. In spring 2023, Twitter has shut down free access to its API for researchers, and tech companies have generally become more wary that their rivals might train AI on their user data.

The authors also specifically contrast their proposal with the “International Panel on the Information Environment” that was launched in May 2023 by the PeaceTech Lab, which they say lacks independence as it's (indirectly) funded by big tech. The authors argue that findings of an independent panel on topics like misinformation might sometimes clash with the economic interests of big social media platforms.

The authors do not comment on (and may not have been aware of?) the International Observatory on Information and Democracy which is also based on the IPCC-analogy and independent of big tech.

A.8 Geoff Mulgan et al. (2023)

In July 2023, a group of academics linked to the Artificial Intelligence & Equality Initiative of the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs made a proposal for a Global AI Observatory. They put this idea forward in an essay in Noema magazine, in an article for the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, and in an article for the MIT Sloan School of Management website.

Example quote:

“The world already has a model for this: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Set up in 1988 by the United Nations with member countries from around the world, the IPCC provides governments with scientific information and pooled judgment of potential scenarios to guide the development of climate policies. Over the last few decades, many new institutions have emerged at a global level that focus on data and knowledge to support better decision-making — from biodiversity to conservation — but none exist around digital technologies.

The idea of setting up a similar body to the IPCC for AI that would provide a reliable basis of data, models and interpretation to guide policy and broader decision-making about AI has been in play for several years. But now the world may be ready thanks to greater awareness of both the risks and opportunities around AI.”

A.9 Lewis Ho et al. (2023)

In July 2023 several leading AI policy researchers from Google DeepMind, OpenAI, Oxford, Harvard, Stanford, as well as Turing-award winner Yoshua Bengio published a joint paper outlining options for international institutions for advanced AI.

The authors suggest four possible novel institutions: An advanced AI governance agency, a frontier AI collaborative, a commission on frontier AI, and an AI safety project.

The Commission on Frontier AI is inspired by the IPCC:

“Existing institutions like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Scientific Assessment Panel (SAS), which studies ozone depletion under the Montreal Protocol, provide possible models for an AI-focused scientific institution. Like these organizations, the Commission on Frontier AI could facilitate scientific consensus by convening experts to conduct rigorous and comprehensive assessments of key AI topics, such as interventions to unlock AI’s potential for sustainable development, the effects of AI regulation on innovation, the distribution of benefits, and possible dual-use capabilities from advanced systems and how they ought to be managed.”

A.10 Mustafa Suleyman et al. (2023)

In the lead up to the Bletchley Summit on AI Safety organized by the UK, a group of leading technologists and leading think tankers have suggested that the event should be used to create an IPCC for AI.

In August 2023, there was an op-ed in Foreign Affairs by Ian Bremmer and Mustafa Suleyman, which suggested multiple interventions, including an “IPCC for AI”:

“To create a baseline of shared knowledge for climate negotiations, the United Nations established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and gave it a simple mandate: provide policymakers with ‘regular assessments of the scientic basis of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and options for adaptation and mitigation.’ AI needs a similar body to regularly evaluate the state of AI, impartially assess its risks and potential impacts, forecast scenarios, and consider technical policy solutions to protect the global public interest. Like the IPCC, this body would have a global imprimatur and scientific (and geopolitical) independence. And its reports could inform multilateral and multistakeholder negotiations on AI, just as the IPCC’s reports inform UN climate negotiations.”

In October, there was another op-ed from Mustafa Suleyman and Eric Schmidt in the Financial Times that exclusively focused on the idea of an “IPCC for AI”:

“We believe the right approach here is to take inspiration from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Its mandate is to provide policymakers with “regular assessments of the scientific basis of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and options for adaptation and mitigation”. A body that does the same for AI, one rigorously focused on a science-led collection of data, would provide not just a long-term monitoring and early-warning function, but would shape the protocols and norms about reporting on AI in a consistent, global fashion. (...) The UK’s forthcoming AI safety summit will be a first-of-its-kind gathering of global leaders convening to discuss the technology’s safety. To support the discussions and to build towards a practical outcome, we propose an International Panel on AI Safety (IPAIS), an IPCC for AI.”

Finally, a couple of days ahead of the AI Safety Summit, a group statement published on the Carnegie website made a proposal with more concrete design principles:

Global engagement - include experts from around the world.

Science-led and expert-driven - pool knowledge from the private sector, academia, the government, and civil society.

Focused on AI safety and security

Respect and protect intellectual property (of AI companies)

No regulatory or policymaking authority, but develop respect and trust to inform policymakers.

Advance new internationally recognized benchmarks for progress and developments in AI.

Stable funding base for analytic independence.

The signatories are Mustafa Suleyman (then - CEO, Inflection; now - VP for AI, Microsoft), Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar (President, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), Ian Bremmer (President, Eurasia Group), Jason Matheny (CEO, RAND), Philip Zelikow (former US Diplomat), Eric Schmidt (former CEO of Google; Chair NSCAI), and Dario Amodei (CEO, Anthropic).

A.11 Jason Hausenloy & Claire Dennis (2023)

In their September 2023 working paper for the Centre for Policy Research of the United Nations University the authors look at the potential role of the UN in AI, specifically evaluating four analogies, one of which is the idea of an “IPCC for AI”:

“Like climate change, AI has unpredictable consequences that cross generations and borders, leading numerous researchers to propose a global AI observatory similar to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Of the four models examined, the IPCC model seems the most promising as a first step in global foundation AI governance. In our recommendations, we propose a similar, scaled-down version for a new international institution. (...) The IPCC principally serves as an advisory body of scientists tasked with collecting and collating scientific consensus on issues related to climate change. It then offers policy relevant recommendations which carry weight due to its intergovernmental approach.”

The authors list a number of advantages and challenges of an “IPCC for AI”.

Advantages include the credibility of an UN-based expert panel for developing countries and China (G77) as well as the low cost.

Challenges include divergent risk perceptions amongst AI experts and a lack of transparency from foundation model providers.

A.12 UN Advisory Board on AI (2023)

The UN Advisory Board on AI is a multistakeholder group of experts set-up at the behest of the UN Secretary-General António Guterres to advise on the Global Digital Compact. The members of the Advisory Board were appointed in October 2023 and in December 2023 the group published an “Interim Report: Governing AI for Humanity” that maps the landscape and looks at options.

The report looks at seven institutional functions that the UN might fulfill:

“Institutional Function 1: Assess regularly the future directions and implications of AI

There is, presently, no authoritative institutionalized function for independent, inclusive, multidisciplinary assessments on the future trajectory and implications of AI. A consensus on the direction and pace of AI technologies — and associated risks and opportunities — could be a resource for policymakers to draw on when developing domestic AI programmes to encourage innovation and manage risks.

In a manner similar to the IPCC, a specialized AI knowledge and research function would involve an independent, expert-led process that unlocks scientific, evidence-based insights, say every six months, to inform policymakers about the future trajectory of AI development, deployment, and use.”

A.13 Emma Klein & Stewart Patrick (2024)

In March 2024, researchers from Carnegie’s Global Order and Institutions Program published a report that looks at the global regime complex for AI governance. Building scientific understanding is one of the identified functions and the authors highlight that this is often framed along analogies, in particular to the IPCC.

“The IPCC offers an appealing governance model. First, it is ostensibly policy neutral, meaning it does not adopt a stance on actions that countries should pursue. (...) Second, the IPCC publishes periodic special reports (on subjects like the implications of global warming of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius or on the ramifications of climate change for Earth’s oceans and frozen regions), which illuminate areas where future governance initiatives are needed (...)

As a research subject, AI is notably different from climate change, biodiversity, and the ozone layer, so establishing a scientific assessment panel for AI will involve addressing additional complexities and trade-offs. First, the rapid speed of AI innovation conflicts with the IPCC’s painstaking, multiyear assessment cycles. (...) Second, policymakers need to decide on a governance model for the assessment body or bodies for AI and determine the precise role of the private sector.”

A.14 UN Global Digital Compact (2024)

In April 2024, the facilitators of UN Global Digital Compact shared the initial Zero Draft. The draft followed the recommendation of the UN Advisory Board on AI and included a multidisciplinary “International Scientific Panel on AI” that would create reports every 6 months.

In May 2024, the facilitators shared the revised first draft, in which the name for the panel was broadened to “International Scientific Panel on AI and Emerging Technologies” and the recommended interval for reports was removed. Current formulation:

“Establish, under the auspices of the UN, an International Scientific Panel on AI and Emerging Technologies to conduct independent multi-disciplinary scientific risk and evidence-based opportunity assessments. The Panel will issue reports, drawing on national and regional horizon-scanning initiatives; and contribute to the development of common assessment methodologies, AI definitions and taxonomies as well as mitigation measures.”

Original in French: “Je souhaite que nous puissions aller jusqu’à créer un GIEC de l’intelligence artificielle, c’est-à-dire véritablement de créer une expertise mondiale indépendante qui puisse mesurer, organiser le débat collectif et démocratique sur les évolutions scientifiques de manière totalement autonome, de manière totalement indépendante (...) il revient aux Etats, aux puissances publiques d’investir en la matière et de garantir le cadre mondial de cette indépendance à travers ce GIEC de l’intelligence artificielle.”

IPCC. (2013). Principles Governing IPCC Work. ipcc.ch p.1

“10. In taking decisions, and approving, adopting and accepting reports, the Panel, its Working Groups and any Task Forces shall use all best endeavours to reach consensus.” IPCC. (2013). Principles Governing IPCC Work. ipcc.ch p.2

e.g., “Since 1988, the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has brought about scientific consensus on the reality of and significance of global warming, which many experts initially refused to admit. We need a similar type of mechanism for biodiversity.” - Jacques Chirac, 2005

This is generally defined as 1850-1900, when reliable instrumental temperature records start to be available. So, even though the reference period is usually called “pre-industrial” in climate policy, it is strictly speaking after the First Industrial Revolution (1780-1840) in Britain.