Imagine a new house for $500, a car for $50, a wedding planner for $2, a medical check-up for 10 cents, or a custom-built app for just 5 cents.

A recurring idea in discussions of the economics of AGI is that it could lead to massive, economy-wide deflation. The reasoning is that AI labor is already cheaper than human labor, will continue to become exponentially cheaper, and will replace human labor in most goods and services. In theory, this could lead to a significant decrease in production costs across various industries. In a perfectly competitive market, prices of goods and services tend to fall in proportion to the decrease in production costs.

A more specific version of the argument, repeated by Ray Kurzweil (e.g., 2007, 2009, 2012, 2018, 2021), is that Moore’s Law means that the price of computation is exponentially decreasing. He then suggests that as computers and AI become integral to all goods and services, we'll experience a 'Moore's Law for Everything,' where prices across the board decrease exponentially, mirroring the trend in computational costs

The problem is that claims about deflation are not primarily claims about technological progress but about monetary policy. In other words, if AGI causes significant deflationary pressures, the second-order effect is that central banks change their monetary policy. Let’s walk through the scenario.

1. Why AGI might create less deflationary pressure than expected

Let’s assume the AI system “GPT-X” is a 1:1 economic substitute for Alice. Alice works as a copy editor and gets an annual salary of 80’000 USD for her services. Let’s assume the accumulated cost to replace Alice with AI is 20’000 USD.

Not all cost reductions lead to price reductions

If the AI supply chain is concentrated, it is likely that one or multiple monopolies may be able to capture a significant fraction of the difference between 20’000 USD and 80’000 USD as profits. For example, GPT-X may be sold at the price of 75’000 USD, which is still 5’000 USD cheaper than Alice to the end-user. The remaining difference between the market price and accumulated cost is the cumulative profit, spread across companies in the AI supply chain (e.g. OpenAI, Microsoft, NVIDIA, TSMC, ASML etc.). In this case 55’000 USD.

In contrast, if we assume that every step of the AI supply chain would be nearly a perfect competition then almost all of the production cost reduction leads to a price reduction. Hence, the AI copy editor service would be sold at close to 20’000 USD per year.

Maybe only some goods and services get cheaper

The following are the categories used by the FED to measure inflation.

Food and beverages (breakfast cereal, milk, coffee, chicken, wine, full service meals, snacks)

Housing (rent of primary residence, owners' equivalent rent, utilities, bedroom furniture)

Apparel (men's shirts and sweaters, women's dresses, baby clothes, shoes, jewelry)

Transportation (new vehicles, airline fares, gasoline, motor vehicle insurance)

Medical care (prescription drugs, medical equipment and supplies, physicians' services, eyeglasses and eye care, hospital services)

Recreation (televisions, toys, pets and pet products, sports equipment, park and museum admissions)

Education and communication (college tuition, postage, telephone services, computer software and accessories)

Other goods and services (tobacco and smoking products, haircuts and other personal services, funeral expenses)

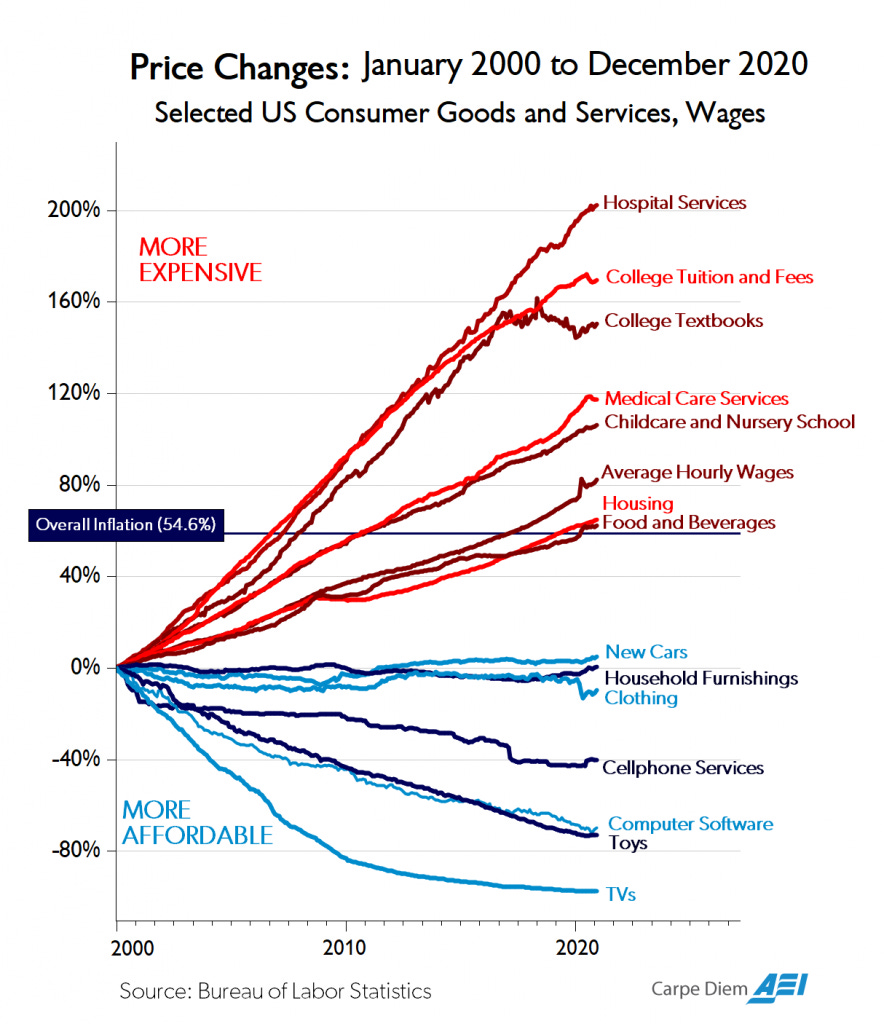

The abundance of different types of goods has historically increased at vastly different speeds. If AGI continues in the path of previous technologies it only makes a dent in a few of these categories. In other words, it creates some deflationary pressures. However, the overall deflationary pressure is limited because other categories of consumption goods and services may increase their relative size in the basket of consumer goods.

One explanation for divergent inflation rates by category would be that we can only replace human labour in some sectors and not others (e.g. due to regulation). Additionally, it’s good to be aware that this is not just a question of production cost development but of rent seeking. Rent seeking involves gaining income without contributing new value to the economy. In other words, some industries may manage to weaponize some dependency to seek rents and just milk consumers dry, profiting from productivity in other sectors.

College textbooks are an example of price evolution that cannot be explained by production costs. The marginal cost of copying and distributing knowledge is near zero today. Instead, this is professors using their monopoly on defining the right textbook for their class, which in turn depends on returns on credentialism. In short, it does seem likely that rent seekers will find a way to capture a part of the AGI profits and that inflation rates for different goods and services will continue to diverge as much as they do now.

Still, let’s assume that after profits in the AI supply chain and rent seeking across domains, there is still significant deflationary pressure. What happens then?

2. Central banks have the mandate to maintain moderate overall inflation

Individual goods and services in an overall basket of consumer goods, such as computer chips, can deflate significantly. However, central banks would not simply allow economy-wide deflation or even hyperdeflation. Inflation targeting is at the core of central bank mandates. Central banks like the European Central Bank (ECB), the Federal Reserve (Fed) in the United States, and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) generally aim for around 2% of inflation. Central banks prefer moderate inflation over deflation for several reasons:

Economic activity: With moderate inflation, consumers and businesses are incentivized to spend and invest, which can stimulate economic activity, rather than to hoard cash. In deflationary periods, consumers might delay purchases of non-essential or durable goods in anticipation of lower prices, which can reduce overall demand and slow economic growth.

Public debt: Deflation increases the real value of debt, making it more expensive for borrowers to repay loans. Inflation decreases the real value of debt, making it cheaper for borrowers to repay loans. Given the high levels of public debt, it is much easier to repay them with moderate inflation.

Wage adjustments: Positive inflation allows for more natural adjustments in real wages without nominal wage cuts, which are often resisted by workers.

Implication: Computer software got 50% cheaper between 2000 and 2020. However, if the entire economy experienced the same level of deflationary pressure as the software industry, central banks would have intervened more aggressively to meet their inflation targets. As a result, software prices might have stabilized or even increased due to monetary policy actions. The overall inflation rate of 54.6% from 2000 to 2020 is not primarily driven by technological progress but by central bank inflation targeting. As you can calculate yourself, it roughly matches the FED’s inflation target of 2% per year (1.02^20 ≈ 1.485). Unless the FED abandons the centrality of inflation targeting the overall inflation for a basket of consumer goods for the next 20 years will be in the same ballpark.

So, how can a central bank achieve its inflation target?

3. Money printer go brrr

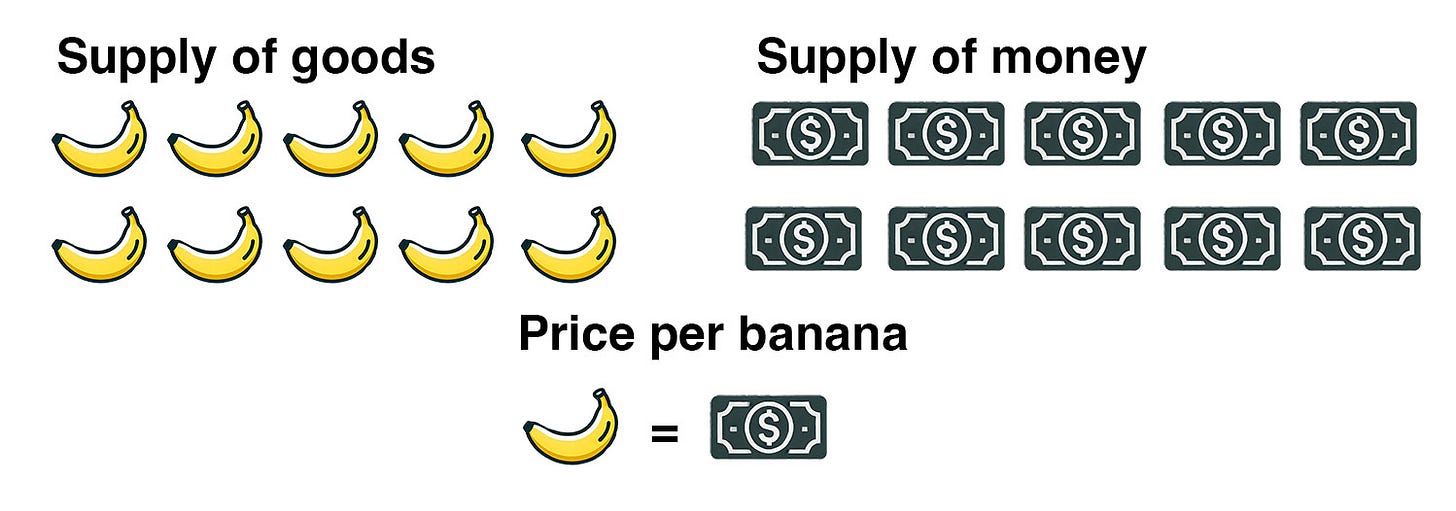

The price of goods and services is fundamentally driven by how much money is chasing how much goods and services. We can illustrate this with a highly simplified model of an economy that consists only of bananas and money.

Suppose we have a closed economy that produces 10 bananas per year which are sold simultaneously.1 The only accepted means of buying bananas is money, which only exists in cash with a total supply of 10 money units that can only be used to buy bananas.

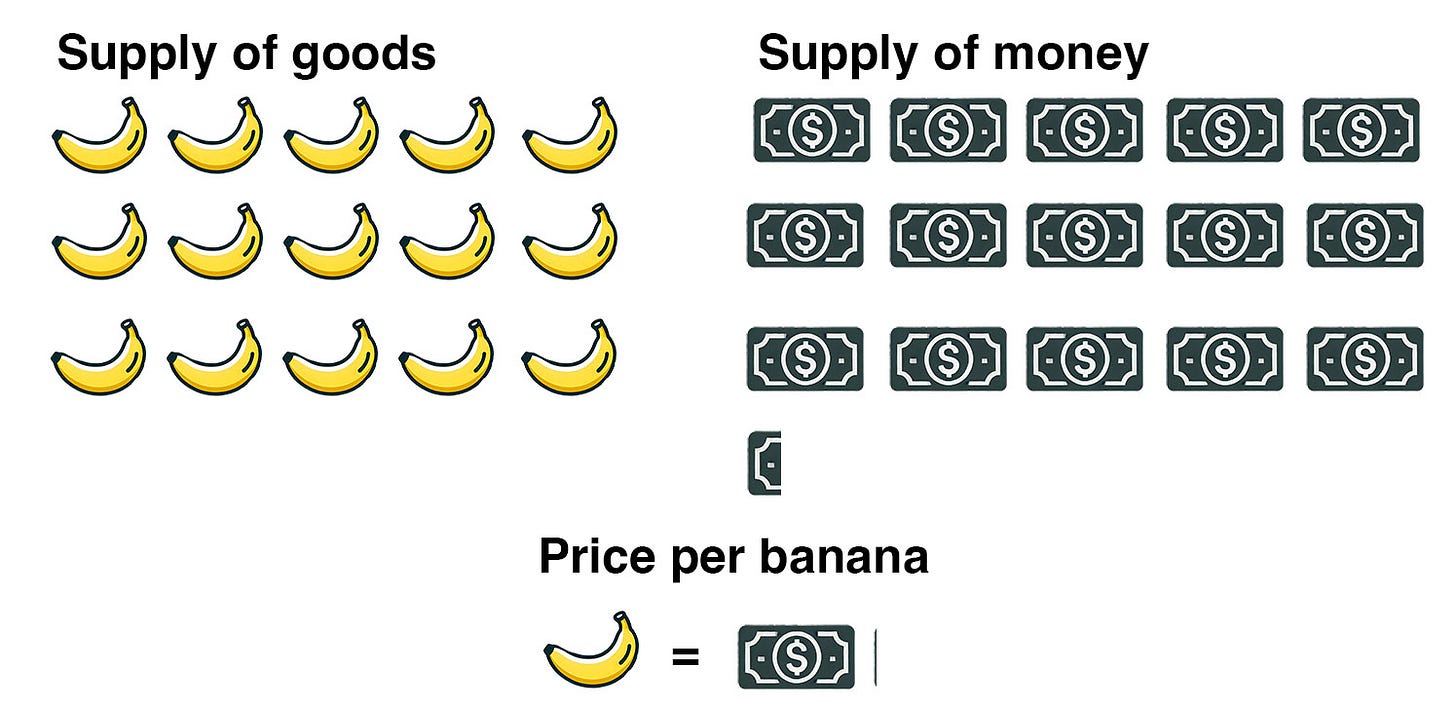

Now, let’s assume AI leads to a revolutionary improvement in banana production. The banana output of the economy increases by 50% in the next year, whereas the amount of money in the economy stays the same. As a consequence, the price per banana falls.

In contrast, if production is increased by 50% and the amount of money in the economy is also increased by 50% prices stay the same. If we increase the money supply slightly more than the increase in banana production—say by 53%—we can achieve a modest inflation rate, approximately the desired 2%

Central banks have the ability to increase the amount of money in circulation by arbitrary amounts. Modern currencies like the US dollar are Fiat currencies meaning they are only backed by being legal tender, the legally accepted currency in an economy. They are not exchangeable at any fixed rate to any naturally scarce resource. Furthermore, most money these days only exists digitally. So, there are few technical barriers to central banks issuing arbitrary amounts of new money.

Seigniorage refers to the profit made by a central bank when it issues currency, as the cost of producing money is less than its face value. When central banks increase the money supply to counteract deflationary pressures that can generate seigniorage revenue. The Federal Reserve and most central banks transfer their net earnings to the government. If there are significant deflationary pressures in an AGI scenario seigniorage might become a more important source of income for governments than it is today.

4. Monetary policy for strong deflationary pressures

It is possible that traditional approaches to introduce new money into the economy would be insufficient under strong deflationary pressures. Not because you can’t print enough money, but because the money made available to commercial banks for loans or by inflating asset prices may not translate to sufficient demand for consumer goods.

Traditional methods of injecting more money into the economy

Interest rates: By cutting the interest rate at which banks borrow from the central bank, central banks encourage commercial banks to increase lending. However, negative interest rates have limitations:

They penalize banks for holding reserves.

Savers and investors may shift to cash holdings or anything else if they receive negative interest on their bank account.

Open market operations: The central bank buys government securities from commercial banks. When the central bank purchases these securities, it pays the commercial banks with newly created money. This increases the banks' reserves, enabling them to lend more money to businesses and consumers.

Quantitative easing: Central banks may purchase government securities and other financial assets, to inject liquidity directly into the financial system. This is an expansionary monetary policy aimed at stimulating economic activity. However, potential drawbacks include:

Inflating asset prices, possibly creating bubbles.

Widening wealth inequality, as asset owners benefit disproportionately.

Limited impact on consumption if businesses or households remain risk-averse.

If traditional monetary policies prove insufficient to counteract the deflationary pressures induced by AGI, central banks might need to consider more unconventional methods.

Helicopter money

"Helicopter money," refers to the direct distribution of money from central banks to the public. By putting money directly into consumers' hands, helicopter money could stimulate demand for goods and services, thereby offsetting deflationary pressures.

Perishable currency: If necessary, it would even be possible to design this money in a way that means it can only be used for specific goods, in specific regions, and/or for a specific time. This “gift card” approach that some of the (government-financed) South Korean UBI experiments have used, would provide the most certain way to stimulate demand for consumer goods.

“Printing” a sovereign wealth fund

A sovereign wealth fund is a publicly owned fund that has a diversified portfolio of assets to generate returns that fund government activities or distribute dividends to citizens. As we explored in the posts on Alaska, Norway and Nauru sovereign wealth funds are traditionally backed by natural resources or another source of government surplus.

However, there is another pathway. Central banks can expand the money supply by directly or indirectly buying a diversified portfolio of assets with significant exposure to global stocks. This sounds crazier than it is.

Japan: In its fight against deflation The Bank of Japan has started buying ETFs that broadly cover the Japanese stock market in their purchases. From 2010 to 2023 the central bank has been accumulating about 500 billion USD worth of domestic Japanese stocks, which corresponds to about 7% of the entire Japanese stock market.

Switzerland: Since 2011 the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has created Swiss Francs and bought large amounts of euros and dollars to combat deflationary pressures and maintain competitiveness of Swiss exports. As a result, the SNB's balance sheet has grown to more than 100% of Switzerland's GDP. Eventually, SNB decided that it doesn’t make sense to hold its more than 800 billion USD of foreign currency reserves idle. As of September 2024, equities made up about 25% of the SNB's foreign currency investments (for comparison in the Norwegian fund equities are 70%+) .

Note that both the Japanese and the Swiss investment activities above are not housed in an independent sovereign wealth fund. Meaning, they are currently managed with monetary policy objectives in mind, not primarily for wealth maximization. Still, Japan and Switzerland have “printed” a large portfolio that could (and in my opinion should) be transformed into a sustainably wealth-maximizing sovereign wealth fund.

So, one non-traditional-idea could be for central banks to counter potential strong deflationary pressures by “printing” a sovereign wealth fund, which in turn could distribute dividends to citizens.

5. AGI + monetary policy

In this post we have looked at the scenario in which AGI significantly reduces production costs for a lot of goods and services and highlighted why and how central banks might respond to this. Overall, this is still a very speculative topic. There is simply no existing literature on the intersection of monetary policy and AGI.

Still, if designed right, monetary policy might be one of the key tools to ensure that everyone profits from automation. Hence, I would encourage monetary economists to take AGI seriously, and I would encourage the AGI people to take monetary policy seriously.

Thanks to

, & for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay. All opinions and mistakes are mine.

In point 2 you discuss 3 reasons why central banks target inflation: promote economic activity, make public debt burden less bad, avoid nominal wage decreases which workers dislike. The first and third of these seem much less relevant in a situation where we are seeing major deflation as a result of AGI.

For the first, I imagine there's tons of economic activity happening because production is through the roof, people want to consume a bunch because they can because prices are lower! And even if people are hoarding cash a bit more than they were before, we're seeing a ton of growth anyway due to the whole AGI automation thing. Monetary policy intended to stimulation economic activity just doesn't seem all that relevant if you have major automation. You're probably seeing unprecedented rates of growth without monetary policy trying to encourage that.

For wages, I'm not sure people are going to care too much about nominal wage cuts if we're actually seeing mass production and falling prices. It seems like a kinda crazy world and it's hard to predict what people will think. It seems like mass unemployment may be part of the situation. Now, I could totally imagine printing money for the sake of UBI is relevant to such a scenario, but it seems less critical that the central bank should be fighting nominal wage cuts because workers are opposed to them.

I don't know much about this stuff (either standard or AGI versions lol). It seems to me like inflation is often bad (largely due to wage stickiness), one of the prime benefits of AGI automation is lower prices, and central banks trying to fight this just seems kinda backward. Looking at the reasons you give why central banks target low levels inflation, I'm not convinced they should do this in the case of AGI automation.

It really doesn’t matter if central banks print money to keep 2% nominal inflation, or let prices deflate by 50%. In either situation the real purchasing power of the consumer remains approximately the same, when accounting for salary adjustments.