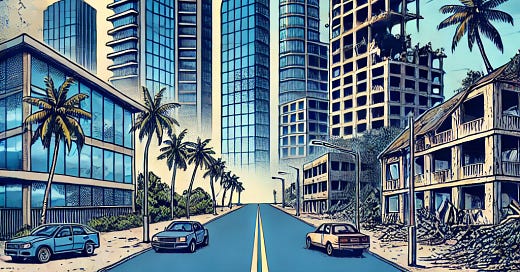

Nauru is a tiny Pacific island nation 3’000 kilometers to the northeast of Australia. Once, it was one of the wealthiest countries per capita in the world, thanks to its abundant phosphate rock deposits, which are derived from bird droppings. Phosphate became the lifeblood of Nauru’s economy, and by the 1980s, the tiny island amassed immense wealth. To manage this windfall, the Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust was created, envisioned as a sovereign wealth fund to ensure that the prosperity would be shared with future generations. However, this plan unravelled in spectacular fashion. Nauru could have reached nearly 4 million dollars of assets per family by 2002 if its fund had the same nominal return as the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund. Instead, due to poor investments and financial mismanagement, the trust had effectively collapsed by the early 2000s.1

In the previous posts on Alaska and on Norway, we have looked at sovereign wealth funds as a solution for governments to ensure sustainable revenues over the long run and gain more exposure to asset classes that we would expect to perform well in an economy with billions of AGIs. However, while it’s good if governments start to think about their “retirement”, it is also important to acknowledge that sovereign wealth funds come with a number of challenges.

The misuse potential of sovereign wealth funds

Political misuse and mismanagement: There is a need to ensure the long-term financial sustainability of a sovereign wealth fund. Specifically, there is a risk of mismanagement and that it could be viewed as a “slush fund” by politicians (e.g. ensuring payouts to constituents before an election).

The pacific islands of Kiribati and Nauru created some of the world’s earliest resource-backed sovereign wealth funds based on the profits from phosphate mining. Kiribati created the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund in 1956. The phosphate mining mostly stopped around 1979 and the fund has been successful in sharing the wealth across generations. However, from 2006 to 2009 the fund substantially declined in value due to underperformance and unsustainable withdrawals. In Nauru the mismanagement problem has been even more pronounced. The Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust, founded in 1968, invested in luxury skyscrapers and high-risk ventures that did not yield returns commensurate with their cost. For example, the trust fund financed the London musical “Leonardo the Musical: A Portrait of Love”, which was co-written and produced by a financial advisor of the fund.

More recently, the Malaysian sovereign wealth fund 1MDB provides an even more egregious example of mismanagement. As unveiled in the 1MDB scandal, fund managers and politicians have diverted billions of USD for personal luxury purchases, including real estate, art, and even financing Hollywood films like "The Wolf of Wall Street."

Strategic concerns: There might be concerns that foreign investments from a sovereign wealth fund are motivated by a military-strategic rather than an investment logic. For example, if a fund owned by the Chinese government would start to systematically buy-up American critical infrastructure, such as ports, the electricity grid, and airports this would raise serious concerns about industrial espionage and the ability and threat of sabotaging critical infrastructure in a conflict. So, recipient countries may want to retain the ability to conduct investment screening and to block sovereign wealth funds from non-trusted countries from taking major stakes in companies in any strategic sectors.

State ownership and private enterprise: There might be more general concerns about a resurgence of state ownership in the economy. In other words, if a sovereign wealth fund acquires majority stakes in a company this approaches “nationalization” or “cross-border nationalization” of companies. In order to avoid excessive meddling of governments in private companies it might make sense to have a code of conduct that sets the limit for individual stakes at a level significantly below the typical threshold of a controlling minority, let alone an absolute majority.

Reciprocity in investment policies: Countries may ask for a principle of reciprocity. The sovereign wealth fund from country A is only allowed to invest in country B if investors from country B are also able to invest freely in country A, the home country of the sovereign wealth fund. Currently many sovereign wealth funds are located in the Middle East and Asia and come from markets that are themselves financially less open than a typical OECD country.

Sovereign wealth funds should be like central banks

Overall, all these challenges point in a similar direction. Specifically, there should be something like a code of conduct with governance prescriptions that ensures that the investment decisions of SWFs are not primarily driven by domestic policy, foreign policy, or personal enrichment. For example, modern central banks are usually designed with a clear mandate, typically focused on or around price stability, and they are largely independent from governments in pursuing their mandate.

Independent investment mandate: SWFs should focus on generating returns, not advancing political, diplomatic, or personal interests. Much like independent central banks are designed to target price stability and are isolated from political pressure, SWFs should also have clearly defined objectives focused on long-term financial stability, growth, and returns.

Transparency and accountability: SWFs should publicly disclose their investment strategies, performance, and risks to ensure transparency. This would build trust with both domestic stakeholders and the international community, avoiding suspicion of hidden political or personal agendas.

There are different investment strategies. However, for many SWFs a low-cost, passive strategy akin to an index funds seems appropriate:

Low-cost, passive strategy: This investment approach is similar to the Norway model. This involves broad market exposure with minimal active management, reducing costs and limiting the risk associated with high-alpha, speculative investment strategies.

Ownership caps: To prevent SWFs from exerting disproportionate control over companies, they could avoid taking more than a 10% ownership stake in any single company. A large minority stake or even a majority stake come with board seats and can blur the lines between passive investing and strategic control.

Overall, these measures can help to mitigate some of the risks of a prominent role of sovereign wealth funds. However, another part of the solution is to ensure that we do not only have public but also widespread private assets that have exposure to the growth of the machine economy. That will be the subject of the next post.

Nauru’s economy has grown again in the 2010s based primarily on finding new phosphate deposits and hosting an asylum seeker processing center for Australia. However, the point here is that the Sovereign Wealth Fund was meant to spread the economic benefits of the first phosphate boom across time and has failed to do so.

It doesn't matter how good an idea if it's not executed well. Appreciate you pointing this out and identifying some core elements for good execution of such a fund.