Here’s an experiment:

1) Think of the main subjects that you were taught in history classes. For example, AP United States History includes The Seven Years’ War, the American Revolution, The American Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War.

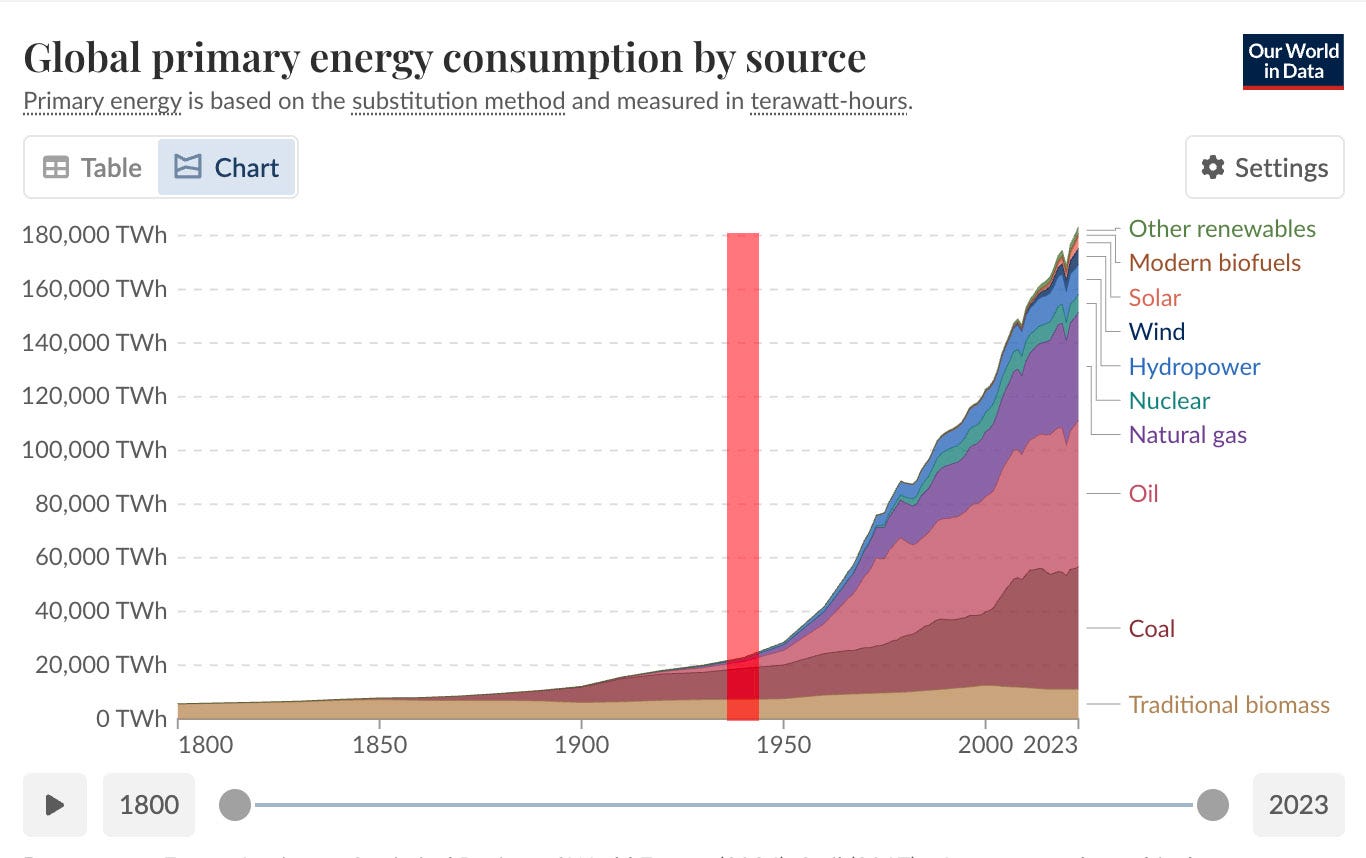

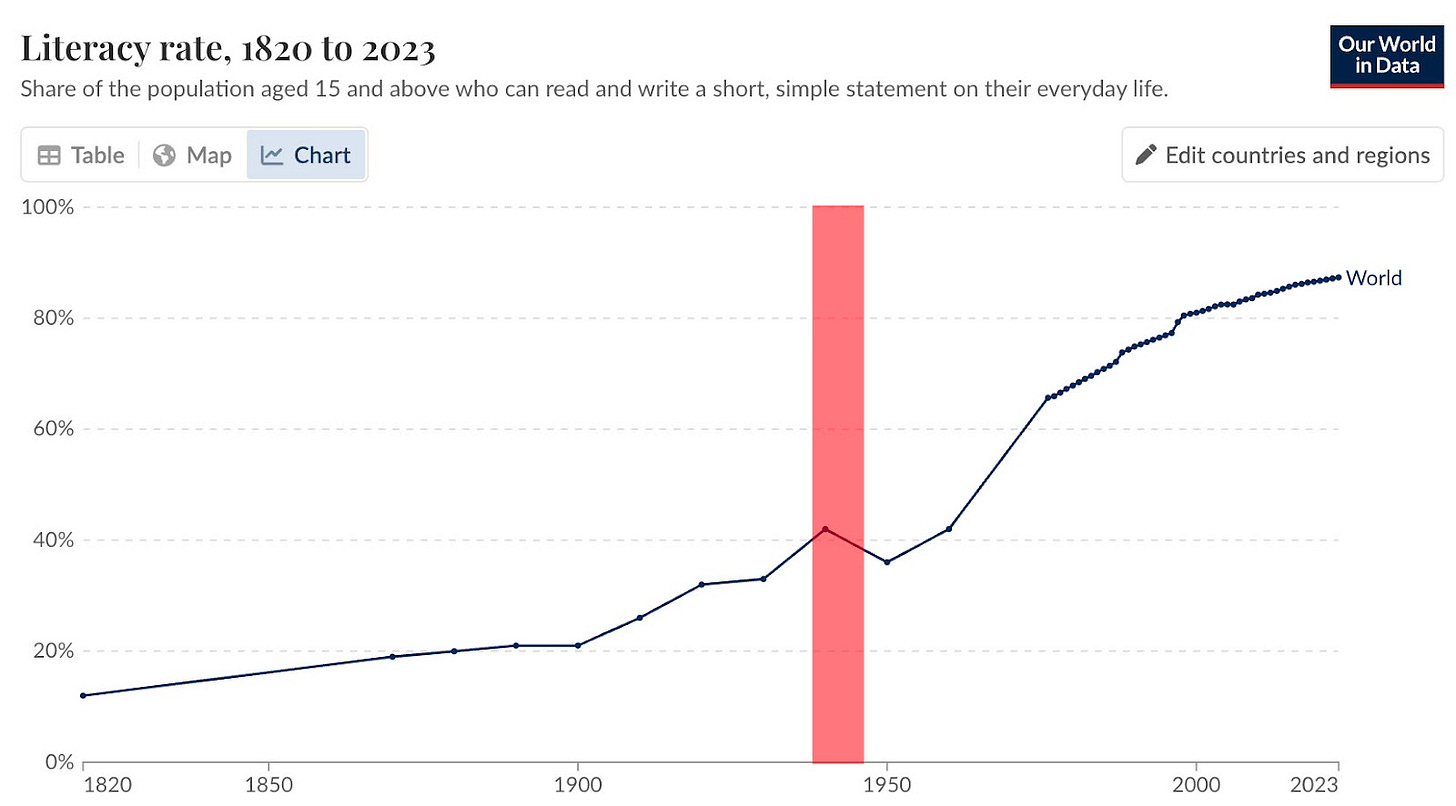

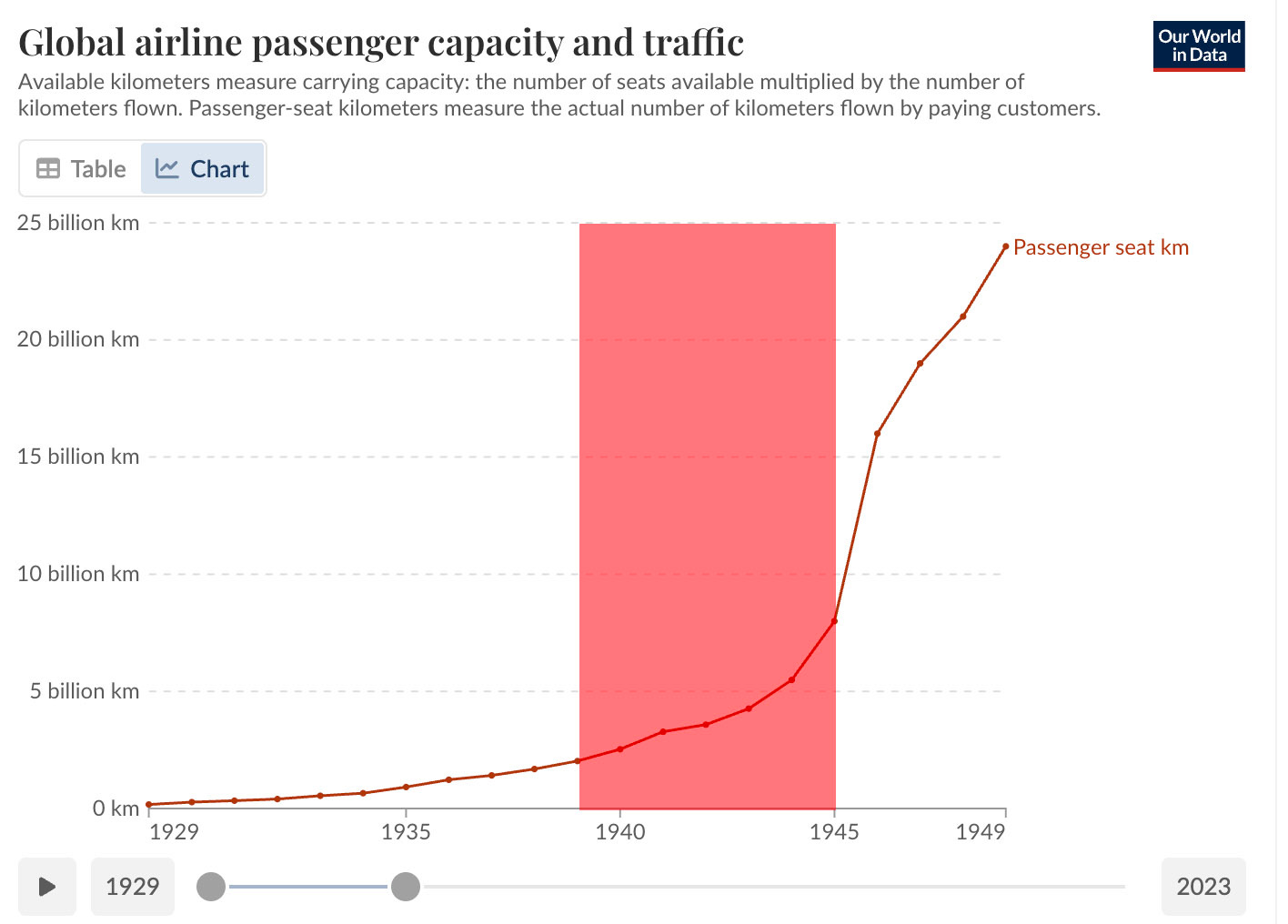

2) Go to OurWorldInData and try to see the impact of the studied events by looking at time series of a range of indicators from health to energy to food to poverty to education.

As an example, let’s choose World War II (1939-1945), the most deadly conflict in human history and arguably the most studied historical subject in the world. There can be no doubt that World War II was a horrible tragedy and a pivotal turn in human history. It caused immense suffering, determined the dominant ideologies of the 20th century and established a new world order.

Yet, when we look at the period 1939-1945 across long-term indicators, such as GDP, life expectancy, or literacy, its visible impact can appear surprisingly modest.

The point of these graphs is not to downplay the horrors and geopolitical consequences of World War II in any way, shape, or form. Nor is it to claim that the effects of a war are confined to the duration of a war.1 Still, what these graphs hint at is that an exclusive focus on wars doesn’t tell us the full story. Counterintuitively, on many long-term statistics, World War II looks more like a temporary disruption, but (luckily) not a fundamental deviation from structural, long-term trends. These long-term trends, which are more incrementally evolving, geographically dispersed processes, should be part of our understanding of history too.

Three ways to look at world history

Understanding the forces that shape history requires looking at different time scales. The French historian Fernand Braudel offers a useful framework to analyze historical change using three distinct lenses:

Event history (shortest time horizon)

Socioeconomic history (intermediate time horizon)

Geographical history (longest time horizon).

Event history: Stories of leaders, wars & breaking news

This is the history we are most familiar with from school. The dramatic political decisions, wars, treaties, and revolutions that seem to turn the tide in a matter of days or years. It’s the realm of heroes and villains.

The following is how a (Western/US-centric) event history of the world might look like:

Event history is good at explaining specific moments and triggers of change. It provides a vivid, human-centered narrative that helps us understand short-term causality. Put simply, it is yesterday's news cycle, sprinkled with declassified material on secretive deals, decisions, and inventions. In contrast, it may largely overlook slower-moving and more distributed structural changes in the social, economic, and technological environment. In Braudel’s own metaphor, events are like waves that ride on the powerful tides of structural history.2

Socioeconomic history: The story of economic growth

This intermediate lens examines social, economic, and cultural structures that change over decades or centuries. There are multiple indicators that we can look at, but arguably the most powerful is world GDP. GDP is a flawed measure that doesn’t include assets, such as natural resources or public infrastructure. Still, world GDP can be a proxy for technological progress, economic complexity, human development, and many other factors.

This view of history tells a fairly continuous story in which major events such as world wars are mere blips. There is a clear sense that history is moving in a direction. The world GDP curve is so steep that you would not want to sit on it.

Geographical history: The story of the Anthropocene

The third and deepest lens zooms out to consider the physical environment and its changes over centuries or even millennia. A world history through this lens is a history of the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is a proposed geological epoch that highlights the significant and widespread impact of human activities on the Earth's systems.

These changes are evident across various indicators. The best known is the anthropogenic increase in atmospheric CO2 due to fossil fuel burning and deforestation, leading to global warming and climate change.

The Anthropocene is generally traced back to the Industrial Revolution, when fossil fuel combustion began to significantly alter atmospheric composition. However, other milestones, such as the post-World War II economic boom and the beginning of nuclear weapons testing, have also been suggested as key markers for its onset.

Event history can miss the forest for the trees

Event history remains the dominant lens through which most history is taught in schools, and how it is studied by most researchers. Event history is great in explaining the microcontext of how key decisions have been made. However, it can also provide a fragmented macroview of history, consisting of isolated stories, and there is no clear sense in which history is moving in a direction. Economic or technological changes are largely treated as exogenous factors, not as core variables that history can or should explain.

In contrast, the socioeconomic and geographical lenses provide a clear overarching narrative to human history. History is not developing randomly; it has a clear direction. Especially, in the last 200 years or so, we have been in a civilizational take-off. Nearly all indicators from health, to wealth, to destructive capability tell a similar story. That story is that our civilization is not in a static stable-state, rather, it is rapidly expanding based on positive feedback loops which have been fueling exponential growth in our economy and our technology. This civilizational take-off has not been centrally planned; rather, it is an emergent phenomenon, an outcome from millions of decentralised interactions between humans and technology over many years.3

This is a basic but important insight. When Patrick Collison & Tyler Cowen argued in 2019 that “We Need A New Science of Progress“ some balked at this and argued that it’s just another case of tech bro’s reinventing the wheel. After all economic history, industrial history, and history of science are all existing subfields of history. Yet, Collison & Cowen never claimed to invent something completely new or that progress is not studied at all. They claimed that progress is understudied. I wholeheartedly agree.

Understanding the long-term historical trends in social, economic, and technological matters and understanding their drivers should not be a small, fairly obscure subfield of history. It should be a significant part, if not most, of the focus of the field.

To be clear, event history is still important and it should be studied. Furthermore, event history and long-term trends cannot be fully disentangled. However, the overwhelming dominance of event history as the lens through which most historians and teachers approach history is not healthy. A well-rounded history education should include situational awareness of the macrocontext of human history.

But why should a blog focused on AI preparedness care about how history is taught? How we understand the past also shapes our expectations for the future. One barrier to more societal preparedness for advanced AI is arguably that advanced AI futures seem weird, uncertain, and speculative. If the macrohistorical narrative is that of a civilizational take-off, it is much more intuitive that all possible macrofutures are weird.

Our perception of what is “normal” is different from that of nearly all our ancestors and descendants. If we cannot sustain exponential technological growth and face prolonged stagnation the world would arguably become much more zero-sum, and we would likely return to a more fixed social order. From there, we could eventually break out downwards to collapse or upwards back to exponential growth. If we sustain the exponential technological growth of the economy and technology we will soon live in a world that is radically different.

Complement OurWorldInDrama with more OurWorldInData

History books that focus on the words of great leaders tend to be in the realm of event history. In contrast, books that explain socioeconomic or geographic history tend to heavily rely on time series to grasp incrementally evolving and dispersed phenomena (e.g., Stephen Pinker’s “Enlightenment Now”, Ray Kurzweil’s “The Singularity Is Near”, or Brad DeLong’s “Slouching Towards Utopia”4). So, if we want history to be less micro and fragmented, and more focused on the macro trajectory of humanity, there is a very simple solution:

History should be taught with more graphs!

Thanks to

, & for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay. All opinions and mistakes are mineFor example, a non-liberal international order would plausibly have led to less global economic integration and overall slower exponential economic growth post-WW2. So, the war probably has had an impact of the steepness of the long-term trend.

“Troisième partie enfin, celle de l’histoire traditionnelle, si l’on veut de l’histoire à la dimension non de l’homme, mais de l’individu, l’histoire événementielle de Paul Lacombe et de François Simiand: une agitation de surface, les vagues que les marées soulèvent sur leur puissant mouvement.” - Fernand Braudel. (1946). La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l'époque de Philippe II. Préface de la première édition.

Structuralist accounts of history that look at dispersed factors naturally lend themselves to stronger notions of technological determinism than event history, which hones in on a few key decision-makers. However, I want to be clear that this call for a structural lens is not an endorsement of any strong form of determinism. A civilizational take-off and human agency are very much compatible.

This book does not contain as many graphs as the other two, but its narrative is clearly informed by DeLong’s work on creating macrohistorical, economic time series.

Loved this! The idea had never occurred to me, but once pointed out seems blindingly obvious – the hallmark of the best insights.

Excellent article. I agree wholeheartedly with your claim that understanding long-term trends is far more important to history than names, dates, and events (which how history is usually taught). I also believe that Progress Studies can make contributions to understanding the origins and causes of these trends.

I recently published an article very similar to yours as well as a larger series of articles that enables us to tie together the trends of long-term material progress to history in general:

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/the-fundamental-constraints-on-human

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/my-theory-of-human-history-a-series

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/all-of-human-history-in-one-graphic