“I look with envy at my peers in high-energy physics, and in particular at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, a huge, international collaboration, with thousands of scientists and billions of dollars of funding. They pursue ambitious, tightly defined projects (like using the Large Hadron Collider to discover the Higgs boson) and share their results with the world, rather than restricting them to a single country or corporation. (…) An international A.I. mission focused on teaching machines to read could genuinely change the world for the better” – Gary Marcus, 2017

“Our vision for CLAIRE is in part inspired by the extremely successful model of CERN. (…) its structure will be more distributed, as there is less need for reliance on a single experimental facility. It will also have much closer collaboration with industry, to quickly and efficiently transfer new results and insights. Similar to CERN, the suggested structure will allow for the establishment of a common, well-recognised “trademark” for high-quality European AI research.” – CLAIRE, 2018

“(...) we need to increase governance and we should consider limiting access to the large-scale generalist AI systems that could be weaponized, which would mean that the code and neural net parameters would not be shared in open-source and some of the important engineering tricks to make them work would not be shared either. Ideally this would stay in the hands of neutral international organizations (think of a combination of IAEA and CERN for AI) that develop safe and beneficial AI systems that could also help us fight rogue AIs.” – Yoshua Bengio, 2023

The idea of a “CERN for AI” was first put forward by Gary Marcus in 2017. Since then, a range of scientists and politicians have expressed support for a “CERN for AI”. This includes Turing award winner Yoshua Bengio as well as groups from the European Union, France, Germany, India, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Switzerland. However, as always, the devil lies in the details:

“CERN for AI” ≠ “CERN for AI”: Ideas for institutions with the same “CERN for AI” label, may not refer to the same underlying ideas. Indeed, the analogy has been used to refer to almost diametrically opposed ideas.

“CERN for AI” does not always contain a lot of “CERN”: There is no “appellation d'origine contrôlée” for governance analogies. Some may have been substantially inspired by CERN, others may see it more instrumentally as a catchy label for a policy proposal.

This text offers is an overview of 11 proposals and 1 project that have explicitly used the “CERN for AI” analogy. The goal is not to say which proposal is right or wrong, but to understand where the authors come from and how this compares to the actual CERN.

Ultimately, CERN is the product of a specific context. It may serve as an inspiration, but a proposal for AI governance that is more accurate as an analogy to CERN is not automatically better than a proposal with less overlap. Indeed, the text also highlights some differences between AI and CERN, such as commercial interest and divisibility of infrastructure, and further considerations, such as the dependence between research focus and openness.

1. A brief introduction to CERN

To evaluate if and how CERN might provide a blueprint for an institution focused on AI research and/or AI governance, we first need to understand its origins and purposes (1-4) and its research and governance structure (5).

1.1 Advance research in particle physics

CERN is the world’s leading institute on particle physics and operates the world’s biggest particle accelerator by far, the Large Hadron Collider. This accelerator has confirmed the existence of the Higgs boson, which was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013. CERN describes its mission on its website:

perform world-class research in fundamental physics.

provide a unique range of particle accelerator facilities that enable research at the forefront of human knowledge, in an environmentally responsible and sustainable way.

unite people from all over the world to push the frontiers of science and technology, for the benefit of all.

train new generations of physicists, engineers and technicians, and engage all citizens in research and in the values of science.

1.2 Cost-sharing for “big science” infrastructure

In the aftermath of the Second World War many European labs had been damaged or destroyed and there the reconstruction of science had to compete with many other priorities. Particle accelerators are not only expensive, but they are also indivisible. The biggest accelerator is much more likely to make a fundamental science breakthrough than 10 smaller ones. The cost-sharing through CERN allows Europe to operate the world’s biggest particle accelerator. About 70% of the world’s particle physicists work at CERN.

CERN has an annual budget of about 1.4 billion CHF. Member state contributions roughly correspond to GDP. The biggest contributors from outside the EU are the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, and Israel. About half of the expenses go towards personnel, the other half goes to material expenses, such as building and maintaining accelerators and operating expenses such as electricity.1

1.3 European Integration

Even though CERN is based in Geneva, it is not a UN organization. The United States, China, and Russia are all not member states of CERN. Instead, CERN is the distinct product of European integration.2 After the catastrophe of two world wars many inside and outside of Europe urgently wanted to build a security architecture that prevents another conflict between major European powers. Hence, the creation of CERN (1954) happened in a broader context of initiatives aimed at European Integration (e.g., European Coal and Steel Community (1952), Treaty of Rome (1957), Euratom (1957)).

Part of the idea was also that nuclear scientists working in mixed international teams doing unclassified work would develop a more supranational spirit and allegiance. Based on surveys of the political attitudes of CERN scientists this has succeeded.3

1.4 Fundamental, civilian, and open research

CERN is the European Organization for Nuclear Research. The obvious military application of nuclear research is the atomic bomb. The obvious civilian application of nuclear research is nuclear energy. CERN does neither and that’s by design.

The purpose of CERN as defined in Article II of the Convention for the Establishment of a European Organization for Nuclear Research:

“The Organization shall provide for collaboration among European States in nuclear research of a pure scientific and fundamental character, and in research essentially related thereto. The Organization shall have no concern with work for military requirements and the results of its experimental and theoretical work shall be published or otherwise made generally available.”

So, all of CERN’s research has to be fundamental, civilian, and open. An initial French proposal for European cooperation in nuclear research was more applied and modelled on the nuclear research centers in the US (Brookhaven) and UK (Harwell),4 which both include accelerators, but more importantly nuclear reactors and related dual-use and classified research.

However, the United States wanted that the former axis powers Germany and Italy are included in the proposal, which meant it had to be limited to accelerators. Applied nuclear physics was prohibited in Germany in 1946 by Law 25 of the Allied Control Council. As was fundamental scientific research, if it had a military nature or if it required constructions or installations that would also be valuable for applied research of a primarily military nature. In short, having the Germans in, meant having the nuclear reactors out.

This was aligned with a preference for European nuclear scientists to focus on “pure research of the academic type”.5

Applied nuclear engineers have dual-use knowledge. They may be useful to national atomic weapons projects, and they would be snatched up by the Soviets in the case of an invasion of Western Europe.6

The US saw its strength in leading the application of technology, since all CERN research was open the US expected to profit from any breakthrough in Europe anyways.7 Also, the US arguably wanted its own physicists to spend less time on particle accelerators and more time on hydrogen bombs.8

To put it differently: Germany used to have the global lead in physics before the Second World War. Germany has been the biggest contributor to the world’s leading fundamental physics research institute for 70 years now. Germany has no national nuclear weapon, and its civilian nuclear energy industry is not exactly world leading. The situation of Italy is similar.

The academic and civilian nature of its research is what enables CERN to have a very clear Open Science Policy that supports open access to publications, open data, open source software, and open hardware. CERN has produced spillover innovations in areas such as information management, superconductivity, cryogenics, medical imaging and therapies, and it’s part of an immeasurable human drive for discovery. However, the fundamental, civilian, and open research that makes CERN “pure” and prestigious is also what reduces its direct economic or military impact on the nuclear sector. It's a project orthogonal to nuclear energy and nuclear bombs, whose biggest effect on these areas is arguably talent competition.

1.5 Governance and operational structure

CERN Council: The highest authority of the organization responsible for approving programmes of activity, adopting the budgets, and appointing the Director-General who manages the CERN Laboratory. Each of the 23 member states has two representatives: one for the government, and one for the scientific community. Each Member State has a single vote, and most decisions require a simple majority, although in practice the Council aims for a consensus.

Central infrastructure – decentralized analysis: CERN operates a large central laboratory in Geneva with about 2’500 staff and an immense concentration of unique experimental equipment. Staff design, construct and operate the research infrastructure and contribute to the preparation, operation, and data analysis for experiments. However, the infrastructure has a vast community of users from scientific institutes from its member states and beyond (about 1/3 to 1/2 of users of CERN infrastructure are from non-member states).

2. “CERN for AI” proposals

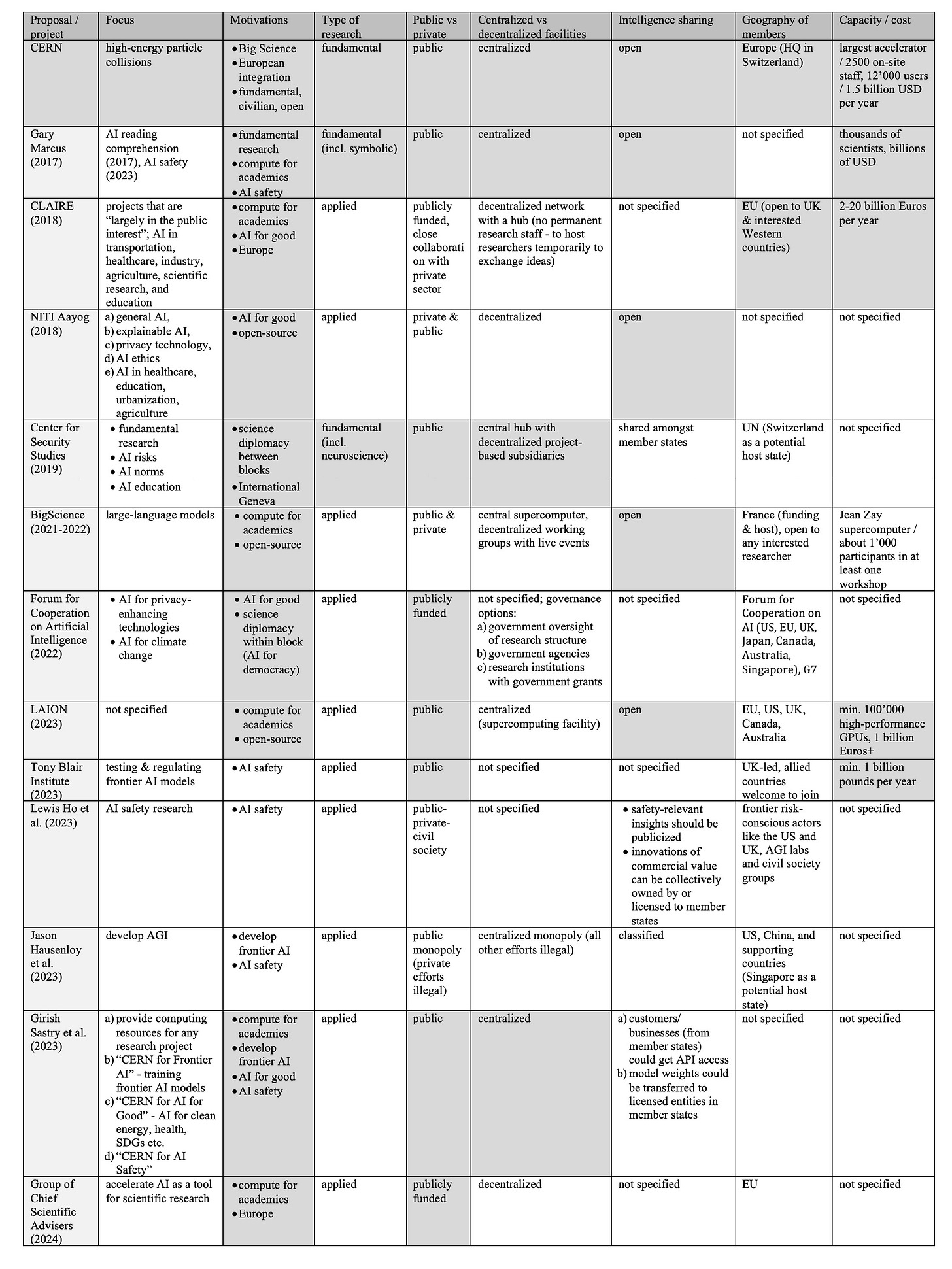

The following is a high-level overview of proposals that have explicitly used the “CERN for AI” analogy. The entries are in chronological order. The first column reflects the proposing authors or their institutional affiliation. Dark grey backgrounds indicate areas where a proposal has substantial similarity to CERN.

To manage the ballooning mental complexity of divergent “CERN for AI” proposals, I think it makes sense to think of them in three approximate clusters:

2.1 Compute for academics

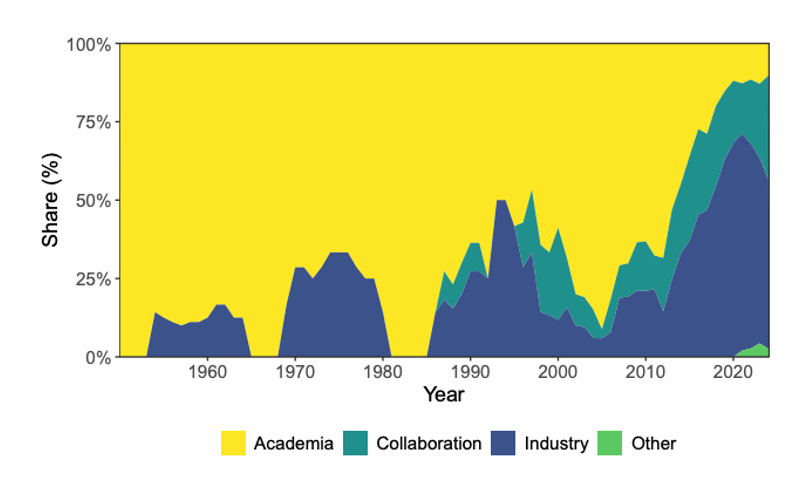

In his 2017 op-ed Gary Marcus argued that “small research labs in the academy and significantly larger labs in private industry” are not sufficient and that we do need publicly funded big science in AI. Indeed, as the interest in commercial AI has taken off, companies have increased their investments in AI models massively. Meaning that most frontier AI models are now developed in industry.

The “CERN for AI” proposals from European academics (CLAIRE, BigScience, LAION, Group of Chief Scientific Advisers) can all be seen as calls for a significant increase in public AI research funding to keep up with colleagues in industry, adding the element of a lack of competitiveness of Europe with the US and China.

Such proposals are combined with various arguments for why the research from the private sector might have shortcomings. The two most common ones are that the private sector is not sufficiently interested in AI applications for social good (“AI for Good”) and that private sector research is not open enough about their datasets and training checkpoints – making it more difficult for academics to experiment with and evaluate cutting edge models.

Concrete models and implementations for these type of proposals include publicly-funded University-independent AI research institutes (e.g., Mila (Canada), Vector Institute (Canada), Technology Innovation Institute (UAE)), publicly-funded AI compute infrastructure for academics (e.g., EuroHPC (EU), National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource (US), AI Research Resource (UK)), as well as publicly-funded AI compute infrastructure for the SDG’s (e.g. International Computation and AI Network (CH)).

2.2 Frontier risk-conscious actors

The AI boom initiated by ChatGPT, has increased concerns about the misuse of AI, the premature deployment of AI systems in critical settings, and the future prospect of losing control over increasingly autonomous and capable AI agents. In 2023, there has been a second wave for “CERN for AI” proposals that primarily come from actors concerned with the safety and security of ever larger frontier AI models. The main idea here is that a joint “CERN for AI” effort could help to accelerate AI safety research (Lewis Ho et al. , Gary Marcus 2023). Other ideas are that it could improve the monitoring and regulation of commercial frontier AI models (Tony Blair Institute), or that there might be some jointly developed frontier model (Girish Sastry et al.) even going as far as arguing for an international consortium developing AGI, while outlawing all other efforts (Jason Hausenloy et al. ).

CERN was not an international Manhattan Project, nor does it work on nuclear safety or nuclear monitoring. However, the analogy may be used in hopes of evoking a more collaborative mindset than other analogies.

2.3 Science diplomacy

Lastly, we have those that view international science collaboration through a primarily political lens. Either as a tool to promote collaboration, to relax the strained relationships between power blocs, and to provide host state services (Center for Security Studies). Or, as a tool to bring researchers from like-minded states closer together and strengthen shared values and standards (Forum for Cooperation on Artificial Intelligence).

The latter is also reflected in the March 2021 report of the US National Security Commission on AI, which argued for creating a Multilateral AI Research Institute (MAIRI) in the United States with key allies and partners. In 2022, researchers from the Stanford Center for Human-Centered AI have made a concrete proposal for how such a MAIRI could look like with an on-site laboratory hosted at an established US university that also allows visiting researchers. The authors recommend that the US should initially fund this multilateral institute unilaterally and determine its members unilaterally.

3. Differences between CERN and AI research

The following points aim to contextualize “CERN for AI” by highlighting that:

the need for publicly funded AI research and publicly operated, centralized AI infrastructure is not as clear for AI as it is for particle accelerators.

the decision on whether to have an open science policy like CERN is linked to the choice of research focus.

there are alternative options to boost European AI in academia and in general.

A longer list of similarities and key differences between the domains of artificial intelligence and nuclear fission will be analyzed in a separate text.

3.1 Commercial interest in research

Particle accelerators would not exist without public funding. There are no commercial operators of larger particle accelerators because the benefits are uncertain, distributed, and too many steps removed from commercialization. AI is the polar opposite. AI is arguably the area of research and development with the single highest commercial interest. A few AI researchers and a few quick slides are enough to raise hundreds of millions. AI research, including a lot of fundamental research, will also get done without public subsidies.

Google Deepmind alone operates on a similar magnitude in terms of annual research budget as CERN (and this does include a lot of fundamental research with neuroscientists and even symbolic AI).

Big tech is not just spending billions to train AI for selling ads. Commercial labs are now beating the average human at reading comprehension and visual reasoning, and many of them explicitly want to build artificial general intelligence.

Hence, the need for publicly funded research is less clear for most areas of AI compared to particle physics. Even “AI for Good” applications are covered pretty well. Having said that, there are some areas in AI that are strategically ignored by the private sector because they might conflict with commercial interests. In an applied sense the obvious issue is laundered data and copyright infringement, where there is a need for more clean, licensable training datasets. In terms of fundamental research with importance and without commercial interest, there could be a case for publicly funded interdisciplinary research on human and AI consciousness.

3.2 Particle accelerators vs. AI accelerators

Many users of the CERN analogy have explicitly compared particle accelerators with AI compute as the expensive infrastructure equivalent. However, there are also some structural differences between the two.

Divisibility of research infrastructure: Larger particle accelerators can achieve higher energies, which are crucial for probing deeper into the structure of matter and for discovering heavier particles that cannot be detected at lower energies. We cannot cumulate the results of 10 lower energy collisions to get the same results as in a high energy collision experiment. In contrast, AI training is highly parallelizable. Meaning that it can be divided into subtasks executed across many GPUs and GPU clusters simultaneously.

Overall, particle accelerators are a single best effort good, whereas compute for a training a specific AI model is closer to an aggregate effort good. Hence, while a rationale for collaboration is there, the need for cost sharing between countries for operating one central infrastructure is less obvious for AI than for particle accelerators. If there are experiments that go beyond the capacities of a national AI datacenter the workload can be split.

Commercial availability of infrastructure as a service: There are no commercial particle accelerator-as-a-service providers. Hence, there is no alternative for academic researchers to publicly owned and operated infrastructure. In contrast, AI compute is largely a commodity that is available as a commercial cloud service. For example, StabilityAI and the Technology Innovation Institute (Falcon models) both largely relied on a commercial AWS EC2 SuperCluster of 4’000+ A100s to train their models. Hence, it is less clear to what degree academic researchers just need funds for infrastructure access, or if there is need for publicly owned and operated AI infrastructure.

3.3 Potential for misuse and military use

Nuclear research as a whole has a lot of potential for misuse and military use. However, the research done at CERN has been specifically selected to have very low potential for misuse and military use. That is what has enabled CERN’s open-science policy (as opposed to Brookhaven).

A “CERN for AI” proposal will face a similar choice. If a “CERN for AI” is to be combined with an explicit open-science policy this will inherently limit the scope of the research and it will probably veer towards some “AI for Good” topic, such as privacy-enhancing technology. In contrast, if a “CERN for AI” is meant to either develop or assess frontier AI models, there is much more potential for misuse and military use, and it seems highly unlikely that states would hand publicly funded frontier AI models on a silver platter to actors such as cybercriminals or rogue states, such as North Korea.

In fact, you may be surprised to learn that the part about particle accelerators that was historically the least open was the high-performance computing. The reason for this is dual-use applications in areas such as weapons design and nuclear testing. The Soviets have repeatedly tried to get access to advanced Western computers for their particle accelerator at the Institute for High Energy Physics in Serpukhov near Moscow. The Soviets first lobbied to get an US-export license for the same computer that CERN had, a CDC 6600. When that failed, they managed to convince the British to sell them two ICL-1906-A. However, the US again vetoed due to concerns that these computers will be covertly diverted for military purposes. In 1971, the US and the UK agreed on a safeguards regime, which involved:

The planning of as full a research schedule as possible for the machines

The necessity of written supporting documentation for individual program runs

Contractual rights of free access by specialists of free world parties which, have cooperation agreements with Serpukhov (presently the United States, the United Kingdom, and France)

Ten-year control over spares and on-site maintenance

ICL willingness to obtain Soviet agreement before export of the computers to permit UK personnel to empty memory cores on demand of their stored informational contents and to transmit them for UK (and US) government analysis.9

The Soviets accepted these conditions. Notably, this was the first Soviet agreement on an inspection regime on Soviet soil. Meaning, a verification regime for high-performance computers is not only possible - in fact, it has preceded similar regimes for nuclear and other weapons.

3.4 European competitiveness in AI

The analysis that Europe is behind both the US and China in AI is arguably correct. However, “CERN for AI” is not the only option to try to change this.

European competitiveness in academia: First, Europe is relatively competitive in AI within academia. The area where Europe is really lagging behind is start-ups and the private sector. Second, yes, more access to AI compute for researchers will help them. Third, arguably the most impactful thing the EU can do for Europe to be a world leader in academic research on AI is to stop holding AI science hostage to politics. Academic institutions have a lot of momentum and only rise or fall over decades – no matter how much money or compute you could theoretically throw at them. The good news is that Europe already has 3 out of the top 11 AI universities worldwide. Oxford in the UK (4), ETH Zurich (7) and EPF Lausanne (11) in Switzerland. Unfortunately, the EU has kicked both countries out of the Horizon program, which makes it artificially difficult for them to collaborate with European researchers and European industry partners. The UK returned in 2024, but the Swiss negotiations are still ongoing.

Industry spin-offs: Academic spin-offs are one way to generate new start-ups. However, as AI becomes a mature large-scale industry, it arguably takes a combination of a local talent pool with implicit industry knowledge. Almost all large AI start-ups in the West are spin-offs from researchers from OpenAI (e.g., Anthropic), Deepmind (e.g., Inflection), or Facebook (e.g., Mistral). So, academia is important for building the talent pool, but getting the leading AI labs to Europe and to do partnerships with European companies is arguably as important for spin-offs.

Annex A – List of proposals for a “CERN for AI”

A.1 Gary Marcus

Gary Marcus first suggested the idea of a CERN for AI at the ITU’s AI for Good Summit in 2017 and followed up with an NYT Op-Ed. The first part of his argument is that deep learning is insufficient for general intelligence. He argued that such systems “can neither comprehend what is going on in complex visual scenes (‘Who is chasing whom and why?’) nor follow simple instructions (‘Read this story and summarize what it means’)” and should be complemented with symbolic AI research.

Marcus argues that this will be solved neither by small academic labs that lack resources, nor by corporate labs that “have the resources to tackle big questions, but in a world of quarterly reports and bottom lines, they tend to concentrate on narrow problems like optimizing advertisement placement or automatically screening videos for offensive content.” Hence, he presents a publicly funded CERN for AI as a potential solution:

“I look with envy at my peers in high-energy physics, and in particular at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, a huge, international collaboration, with thousands of scientists and billions of dollars of funding. They pursue ambitious, tightly defined projects (like using the Large Hadron Collider to discover the Higgs boson) and share their results with the world, rather than restricting them to a single country or corporation. (…) An international A.I. mission focused on teaching machines to read could genuinely change the world for the better — the more so if it made A.I. a public good, rather than the property of a privileged few.”

Marcus has remained an advocate for a CERN for AI over the years (e.g., 2019, 2023). In a blog post in 2023 Marcus elaborated again on the idea, in which he now suggested to focus on AI safety. “Some problems in AI might be too complex for individual labs, and not of sufficient financial interest to the large AI companies like Google and Facebook (now Meta) (…) while every large tech company is making some effort around AI safety at this point, the collective sum of those efforts hasn’t yielded all that much.” He specifically highlights hallucinations, jailbreaking LLMs, and their failure to reliably anticipate consequences of actions.

A.2 Confederation of Labs of Artificial Intelligence Research (CLAIRE)

CLAIRE is the abbreviation for the "Confederation of Laboratories for Artificial Intelligence Research in Europe". The initiative was launched by Holger Hoos (University of Aachen), Morten Irgens (Oslo Metropolitan University) and Philipp Slusallek (German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence).

“Our vision for CLAIRE is in part inspired by the extremely successful model of CERN. (…) In other aspects, CLAIRE will differ from CERN: Despite the central facility, its structure will be more distributed, as there is less need for reliance on a single experimental facility. It will also have much closer collaboration with industry, to quickly and efficiently transfer new results and insights. Similar to CERN, the suggested structure will allow for the establishment of a common, well-recognised “trademark” for high-quality European AI research.” – CLAIRE, 2018

“The time has come for large-scale and effective investment into publicly owned and operated AI infrastructure, along with cutting-edge research and pre-competitive development capabilities. The time has come for a CERN for AI. It would be tragic if the EU missed its chance to lead this effort.” – CLAIRE, 2023

Holger Hoos in particular has repeatedly used the CERN-analogy (2020, 2022, 2023, 2023) to ask European policymakers for AI research funding. Here is how he explains his idea of a CERN for AI:

“A CERN for AI would essentially have three functions. It would serve as a meeting place, a platform for experts to interact and exchange ideas. Second, it would offer a research environment that the various existing research centers, even the large ones, including the Max Planck Institutes, simply cannot finance on their own. Third, it would be a global magnet for talent to create an alternative to the U.S.-based big tech companies. As a public-sector institution, the Center would be accountable to the public and largely seek to solve problems in the public interest.

An AI center of this size would require a one-time investment in the single-digit billion range and probably another 10 billion euros for a ten-year operation period. In other words, we would be talking about a maximum of 20 to 25 billion euros. That sounds like a lot of money, but it certainly can be covered at the EU level – 25 billion euros is far less than a half percent of the annual budget of all member states. And what you get in return is extremely attractive: Unlike, say, particle physics, in AI, the path from the lab to the real world is very short. It would be an investment that would most likely break even within a few years. And we're not talking about important issues such as technological sovereignty yet.”

Within a month of the statement above by Hoos, CLAIRE published a text “Moonshot in Artificial Intelligence” in which they estimate significantly higher cost. My personal sense is that these numbers are not based on any actual calculations:

“We estimate the public funding required for this moonshot at roughly 100 billion Euros, to be invested between 2024 and 2029 by EU member states and associated countries, including the UK, and we advocate including interested non-European partners, such as Canada, Japan and possibly the United States.”

A.3 NITI Aayog

NITI Aayog is the public policy think tank of the Government of India that has been tasked to write a national AI strategy in 2018. The strategy is framed under the title of "AI for all". The idea of a CERN for AI is included based on the discussions at the AI for Good Summit and the idea of “people’s AI” that AI should be distributed widely and adapted to local contexts.

The NITI Aayog report suggests applied research, private sector involvement, and no central hub:

“International Centers of Transformational AI (ICTAI) with a mandate of developing and deploying application-based research. Private sector collaboration is envisioned to be a key aspect of ICTAIs.

The research capabilities are proposed to be complemented by an umbrella organisation responsible for providing direction to research efforts through analysis of socio-economic indicators, studying global advancements, and encouraging international collaboration. Pursuing “moonshot research projects” through specialised teams, development of a dedicated supranational agency to channel research in solving big, audacious problems of AI – “CERN for AI”, and developing common computing and other related infrastructure for AI are other key components research suggested.(…)

While the modalities of funding and mandate for this #AIforAll should be the subject of further deliberations, the proposed centre should ideally be funded by a mix of government funding and contributions from large companies pursuing AI (GAFAM, BATX etc.). Where should this centre be located? Nowhere and everywhere. While the CERN had the requirements of physical facilities such as the Large Hadron Collider, #AIforAll could be distributed across different regions and countries. The Government of India, through NITI Aayog, can be the coordinating agency for initial funding and setting up the requisite mandates and human and computing resources.”

The report suggests multiple potential focus areas for the CERN for AI:

general AI

explainable AI

privacy technology

ethics in AI

AI to solve the world’s biggest problems in healthcare, education, urbanization, agriculture etc.

A.4 Center for Security Studies

In 2019, two of my former colleagues at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich, Sophie-Charlotte Fischer and Andreas Wenger, have called for “a politically neutral, international, and interdisciplinary hub for basic AI research that is dedicated to the responsible, inclusive, and peaceful development and use of AI.” This hub would provide four main functions:

fundamental AI research (incl. neuroscience)

research of technical and societal AI risks

development of norms and best practices for AI applications

serve as a center for learning and education

The authors do not frame this “CERN for AI” in terms of European integration or competitiveness but in terms of science diplomacy across geopolitical divides. Membership should be open to all states and the organization may be “linked to the UN via a cooperation agreement” and suggest Switzerland as a potential host state. The results of its research would be available to member states as a collective good. Switzerland's 2028 Foreign Policy Vision also contains a reference to the idea of a “CERN for AI”.

A.5 BigScience

BigScience is different from other entries in this list in that it is not a proposal, but a project. BigScience was a one-year project from May 2021 to May 2022 by HuggingFace (Amazon), the French government and French academics. The purpose of the project was to train and evaluate an open-source large language model (BLOOM). Specifically, academics complained that they lack access to the training dataset and checkpoints of large language models, which makes it more difficult to study them. They also argued that commercial models from big tech are too anglo-centric in the text corpora used to train these models. The project was framed as a “CERN for AI” and could rely on Jean Zay, an AI supercomputer funded by French Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation, for AI training. As described on its website:

“The BigScience project takes inspiration from scientific creation schemes such as CERN and the LHC, in which open scientific collaborations facilitate the creation of large-scale artefacts that are useful for the entire research community.”

And here is a corresponding quote from Stéphane Requena, the director of the French national agency in charge of high-performance computing and storage resources for academic research and industry:

“One of the first AI projects to use this extension full-time will be the ‘Big Science’ project, which is aiming to develop an open, multi-lingual and ethical Natural Language Processing (NLP) model of up to 200 billion parameters, competing with OpenAI’s GPT-3. This project is gathering more than 600 partners worldwide from academia and industry, including startups, small- and medium-sized enterprises, and other large groups). It is seen as the CERN of NLP.”

A.6 Forum for Cooperation on Artificial Intelligence (FCAI)

The Forum for Cooperation on Artificial Intelligence (FCAI) is a joint project of two think tanks, the Brookings Institution (US) and the Centre for European Policy Studies (EU). Initiated in 2019, it facilitates ongoing “track 1.5” AI discussions involving senior officials from seven countries—Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, Singapore, the U.K., and the U.S.—along with professionals from industry, civil society, and academia. The goal is to identify opportunities for international cooperation on AI regulation, standards, and research and development.

In a 2021 report FCAI mentioned CERN as one possible model for AI R&D collaboration and recommended to hold discussions on potential projects based on six criteria: Global significance, global scale, public good nature of the project, collaborative test bed, assessable impact, multistakeholder effort. In its follow-up 2022 report the authors Cameron Kerry, Joshua Meltzer, and Andrea Renda recommend two concrete areas for R&D cooperation:

prize challenges and standard-setting collaboration for privacy-enhancing technologies

the use AI for climate monitoring and management.

The criterium of multistakeholder effort has been excluded in the follow-up report. Instead, the authors suggest three possible models:

government representatives overseeing a structure of research contributors (CERN)

a handful of government agencies (ISS)

an aggregation of research institutions supported by government grants (HGP)

The authors recommend that FCAI countries should put the suggested opportunities for multilateral R&D on the agenda of the G-7 and other appropriate multilateral and multistakeholder bodies. Separately, they also endorse the Stanford HAI proposal that the U.S. should consider establishing a CERN-like multilateral AI research institute.

A.7 LAION

According to Emad Mostaque, founder of image-generator StabilityAI, the idea of a “CERN for AI” was the initial blueprint for setting up a decentralized, open-source AI community through discord servers: “We kicked it off as CERN but from a discord group from EleutherAI and then it evolved into LAION, OpenBioML and a bunch of these others.” Specifically, Emad rented access to a cluster of about 4’000 GPU’s from Amazon and provided them to open-source AI projects.

LAION is registered as a German non-profit organization that scrapes pictures from all corners of the web to create giant annotated datasets. The non-profit has received AI compute from Emad Mostaque as well as grants on publicly owned supercomputers, most notably, the Juelich Supercomputing Center (Germany), to use AI to create text labels for pictures, remove watermarks etc. LAION’s datasets are formally declared to be for research purposes. Its datasets have been used to train the models of its for-profit sister StabilityAI, but also MidJourney and traditional big tech companies, such as Google.10

In March 2023 the LAION founders started an online petition “Calling for CERN like international organization to transparently coordinate and progress on large-scale AI research and its safety”. Specifically, it called for:

“the establishment of an international, publicly funded, open-source supercomputing research facility. This facility, analogous to the CERN project in scale and impact, should house a diverse array of machines equipped with at least 100,000 high-performance state-of-the-art accelerators (GPUs or ASICs), operated by experts from the machine learning and supercomputing research community and overseen by democratically elected institutions in the participating nations.”

Here are some additional comments on the proposal by LAION co-founder Christoph Schuhmann:

“With a billion euros, you could probably build a great open-source supercomputer that all companies and universities, in fact, anyone, could use to do AI research under two conditions: First, the whole thing has to be reviewed by some smart people, maybe experts and people from the open-source community. Second, all results, research papers, checkpoints of models, and datasets must be released under a fully open-source licence.”

A.8 Tony Blair Institute

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change has released a paper “A New National Purpose: Innovation Can Power the Future of Britain” that gives various policy recommendations to the UK government on AI. One of the recommendations is to build a national laboratory dubbed “Sentinel” that would recruit top talent, have access to substantial resources and that would test & assess the AI models of frontier labs:

“An effort such as Sentinel would loosely resemble a version of CERN for AI and would aim to become the “brain” of an international regulator of AI, which would operate similarly to how the International Atomic Energy Agency works to ensure the safe and peaceful use of nuclear energy.”

Overall, this proposal seems much more aligned with proposals for auditing, testing, and verifying regimes (incl. “IAEA for AI”) than the work of CERN. Presumably, the CERN analogy was added to underline the point that this regulatory institution might also need significant compute infrastructure for testing and/or for attracting top talent to a regulator.

A.9 Lewis Ho et al.

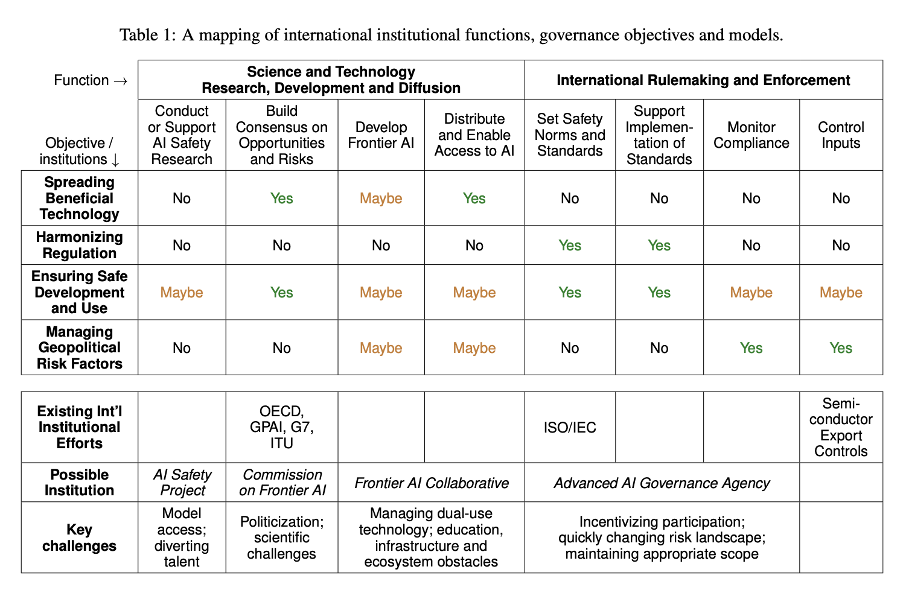

In 2023 several leading AI policy researchers from Google DeepMind, OpenAI, Oxford, Harvard, Stanford, as well as Turing-award winner Yoshua Bengio published a joint paper outlining options for international institutions for advanced AI.

The authors suggest four possible novel institutions: An advanced AI governance agency, a frontier AI collaborative, a commission on frontier AI, and an AI safety project.

The AI safety project is inspired by CERN:

“Tthe [sic] Safety Project would be modeled after large-scale scientific collaborations like ITER and CERN. Concretely, it would be an institution with significant compute, engineering capacity and access to models (obtained via agreements with leading AI developers), and would recruit the world’s leading experts in AI, AI safety and other relevant fields to work collaboratively on how to engineer and deploy advanced AI systems such that they are reliable and less able to be misused. CERN and ITER are intergovernmental collaborations; we note that an AI Safety Project need not be, and should be organized to benefit from the AI Safety expertise in civil society and the private sector.”

Note that this “CERN for AI” proposal is different from the Sentinel “CERN for AI” proposal, which would be the “advanced AI governance agency” in Lewis Ho et al. The goal here would be to accelerate AI safety research, not to monitor the compliance of frontier AI models. The authors highlight two potential challenges for this idea: 1) that it pulls away safety researchers from frontier AI companies, and 2) that frontier AI companies might not want to share access to their models due to espionage / security concerns.

Having said that, co-author Yoshua Bengio also has a FAQ on Catastrophic AI Risks on his blog in which this CERN would also develop frontier AI models:

“(...) to reduce the probability of someone intentionally or unintentionally bringing about a rogue AI, we need to increase governance and we should consider limiting access to the large-scale generalist AI systems that could be weaponized, which would mean that the code and neural net parameters would not be shared in open-source and some of the important engineering tricks to make them work would not be shared either. Ideally this would stay in the hands of neutral international organizations (think of a combination of IAEA and CERN for AI) that develop safe and beneficial AI systems that could also help us fight rogue AIs.”

A.10 Jason Hausenloy et al.

Jason Hausenloy, Andrea Miotti, and Claire Dennis propose a “Multinational Artificial General Intelligence Consortium (MAGIC)” to mitigate existential risks from advanced artificial intelligence. Their proposal is that the US and China, along with an initial coalition of supporting countries build MAGIC: “the world’s only advanced AI facility, with a monopoly on the development of advanced AI models, and nonproliferation of AI models everywhere else.” This would be “among the most highly secure facilities on Earth” and “any advanced AI development outside of MAGIC illegal, enforced through a global moratorium on training runs using more than a set amount of computing power.”

The paper argues that there is some precedent for this in CERN:

“Other large-scale scientific collaborations similarly maintain control over specific technologies through the physical concentration of resources. CERN hosts the world’s largest particle physics laboratory, including the Large Hadron Collider, and retains exclusive access to these facilities.”

In a follow-up op-ed in Time, Andrea Miotti compares the existential risk from nuclear weapons to that of AI and argues:

“While nuclear technology promised an era of abundant energy, it also launched us into a future where nuclear war could lead to the end of our civilization. (…) In 1952, 11 countries set up CERN and tasked it with ‘collaboration in scientific [nuclear] research of a purely fundamental nature’—making clear that CERN’s research would be used for the public good. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was also set up in 1957 to monitor global stockpiles of uranium and limit proliferation. Among others, these institutions helped us to survive over the last 70 years.”

Hence, he argues, there is a need for a “CERN for AI”:

“MAGIC (the Multilateral AGI Consortium) would be the world’s only advanced and secure AI facility focused on safety-first research and development of advanced AI. Like CERN, MAGIC will allow humanity to take AGI development out of the hands of private firms and lay it into the hands of an international organization mandated towards safe AI development. (…) It would be illegal for other entities to independently pursue AGI development. (…) Without competitive pressures, MAGIC can ensure the adequate safety and security needed for this transformative technology, and distribute the benefits to all signatories. CERN exists as a precedent for how we can succeed with MAGIC.”

The other two co-authors Jason Hausenloy & Claire Dennis wrote a paper for United Nations University on the potential role of the UN in AI, in which they look at four analogies (three related to the UN + CERN). Specifically, the authors look at “CERN for AI” in the sense of Lewis Ho et al. (joint AI safety research) and based on their own proposal (joint monopoly on AGI development).

With regards to “Lewis Ho et al.” they note “centralization of AI safety research may limit innovation. A diversity of approaches and research groups would likely yield faster progress. Additionally, while hardware resources could be consolidated, it would be unnecessary to physically relocate researchers to a single location.” With regards to their own proposal, they also admit limits of the analogy: “CERN also did not prohibit the construction of other particle accelerators. Its structure is, therefore, more about common scientific endeavour, rather than limitation of risk.”

A.11 Girish Sastry et al.

In 2024 a group of AI policy researchers from OpenAI, Oxford, Cambridge, as well as Yoshua Bengio wrote a joint paper outlining how compute governance can contribute AI governance. Amongst other things, they highlight that governments could promote preferred uses of AI and slow down negative uses by changing the allocation of compute among actors and projects. In this context, they discuss a number of “CERN for AI” proposals, which they put into three categories:

a “CERN for Frontier AI” could focus on training frontier models

a “CERN for AI for Good” could focus on public goods,

a “CERN for AI Safety,” could focus on improving our understanding of and ability to control the behavior of AI systems

The authors mostly discuss the idea of a “CERN for Frontier AI”, arguing that such an institution might need some kind of structured access or licensing regime for developed frontier AI models, that it might create “cooperation between otherwise adversarial countries” and that it could be “one of the most radical expansions of the power of international organizations in human history.”

However, the authors make no specific recommendation or proposal. Noting that there is “no widespread agreement on what governance of such an organization could look like, or how it could simultaneously satisfy all stakeholders’ demands. The governance structure of a CERN for AI would be an important determinant of how desirable it is, and it is far from clear whether existing proposals provide a satisfactory answer.”

A.12 Group of Chief Scientific Advisors

The Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA) project is an EU-funded evidence review by select academics of policies in different issue areas. In 2024, the AI working group has published its report “Successful and timely uptake of artificial intelligence in science in the EU”, which amongst other things calls for “founding a publicly funded EU state-of-the art facility for academic research in AI, while making these facilities available to scientists seeking to use AI for scientific research, thereby helping to accelerate scientific research and innovation within academia”11

Based on this the EU Group of Chief Scientific Advisors recommends that the European Commission sets up a European Distributed Institute for AI in Science (EDIRAS). This proposed institute would be a “distributed CERN for AI in research” that helps scientists from all disciplines that are members of publicly funded universities and not-for-profit research institutes to undertake cutting-edge research using AI.

Specifically, this distributed institute should:

“provide massive high-performing computational power;

provide a sustainable cloud infrastructure;

provide a repository of high-quality, clean, responsibly collected and curated datasets;

provide access to interdisciplinary talent; and

have an AI scientific advisory and skills unit engaged in developing best practice research standards for AI and developing and delivering appropriate training and skills development programmes.”

CERN. (2022). Final Budget of the Organization for the sixty-ninth financial year: 2023. cern.ch

After the foundation of CERN, there were also ideas of a “world accelerator” more akin to ITER or the ISS that would have involved the United States, the Soviet Union, and CERN, but these did not amount to much in the end. Adrienne Kolb & Lillian Hoddeson. (1993). The Mirage of the "World Accelerator for World Peace" and the Origins of the SSC, 1953-1983. Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, 24(1), 101-124

Daniel Lerner & Albert Teich. (1970) Internationalism and World Politics Among CERN Scientists, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 26(2), 4-10.

John Krige. (2006). American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe. MIT Press. pp. 60-62

John Krige. (2006). American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe. MIT Press. p. 33; Later, the US nevertheless supported a separate European integration effort in nuclear energy (Euratom), but with controls and a significant role for US companies. In contrast, the UK opposed any European effort in nuclear energy, because it did not want to share a scientific lead with other European countries and did not want US companies to get privileged market access. In the end, Euratom never amounted to much.

John Krige. (2006). American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe. MIT Press. p. 33; This should also be read in the context of Operation Alsos, Operation Paperclip and Operation Osoaviakhim. Indeed, arguably the biggest applied German contributions to nuclear science after the Second World War came from Max Steenbeck and Gernot Zippe, Soviet POWs, who invented the process of uranium enrichment through gas centrifuges.

John Krige. (2006). American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe. MIT Press. p. 69

“Our scientific community has been out on a honeymoon with mesons. The holiday is over. Hydrogen bombs will not produce themselves. Neither will rockets nor radar.” – Edward Teller. (1950). Back to the Laboratories. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 6(3), 71-72. p. 72

Mario Daniels. (2022). Dangerous Calculations: The Origins of the U.S. High-Performance Computing Export Safeguards Regime, 1968-1974. In J. Krige (Ed.), Knowledge Flows in a Global Age. University of Chicago Press. p. 158

This practice is also referred to as data laundering