Valéry Giscard d’Estaing served as President of France from 1974 to 1981. In the general public he may be the least well known French President of the Fifth Republic. Yet in recent years he experienced a surprising online renaissance. On Reddit a community of nearly 30’000 users celebrate “Giscardpunk”. Giscardpunk is a mix of 1970s French retrofuturism and alternate history, in which Giscard won the re-election against the Socialist Francois Mitterand in 1981 to lead France into the future. The subreddit is mostly about aesthetics.

Yet, if we dig a bit better deeper, Giscardpunk is a reflection of French industrial policy. Specifically, it is emblematic of the golden years of French “high-tech Colbertism”. Understanding this form of industrial policy is crucial to understanding the French and their thinking on technological sovereignty and AI. And, it may well provide some inspiration for Europe.

1. What is high-tech Colbertism?

High-tech Colbertism is a term to describe the French Industrial strategy until about 1984. The term is derived from Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Controller-General of Finances under Louis XIV. Colbertism combines a set of loose ideas around an interventionist state that promotes specific industries. This does not only include state-sponsored innovation, but mercantilist practices to protect these industries domestically and support their exports abroad.

High-tech Colbertism is Colbertism specifically targeting strategic “industries of the future”. In these industries it emphasises "grand projects," where the state mobilizes resources, finances, and coordinates industries to establish a national champion.

2. French successes

In 1967 “Le Défi Américain” or the “The American Challenge” became an immediate bestseller in France. The book’s core message was simple: America is accelerating, Europe is falling behind. There is a need for a concerted European effort to compete in the industries of the future.

The French elites, driven by a conviction that France must be great, went to work to close the technological gap. Subsequently, in a period of about 5 years France launched some of Europe’s most successful and enduring top-down innovation projects. The French build up of nuclear energy and high speed rail are two foundations that have lasted until today. Most of these foundations were initiated by Georges Pompidou (1969-1974) and continued by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (1974-1981).1

Nuclear energy - Messmer Plan (1974)

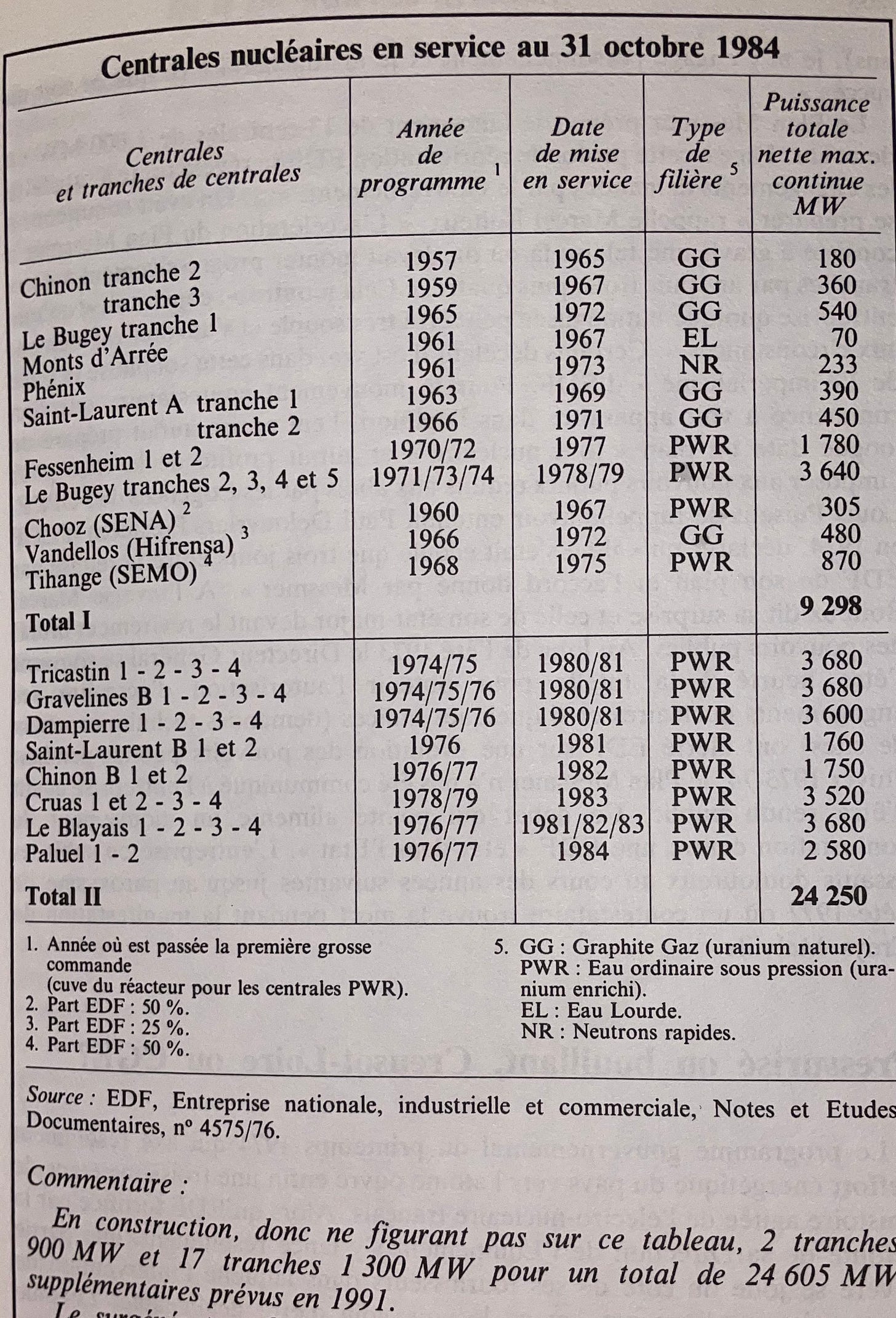

In response to the oil crises of the 1970s, France embarked on an ambitious nuclear energy program known as the "Messmer Plan" in 1974.2

Energy Independence: France reduced its reliance on oil imports, achieving a high degree of energy self-sufficiency.

Environmental Impact: With around 70% of its electricity generated from nuclear power, France has one of the lowest carbon emission rates per unit of GDP among industrialized nations.

Technological Leadership: France became a global leader in nuclear technology, exporting expertise and services.

High-Speed Rail Network - TGV (1974)

The Train à Grande Vitesse (TGV) is France's high-speed rail service.

Technological Excellence: The TGV set world speed records for conventional trains and became a benchmark for high-speed rail technology.

Transportation Efficiency: It revolutionized domestic travel by providing fast, reliable, and energy-efficient transportation, moving more than 100 million passengers per year.

Economic Impact: Boosted regional development and tourism by improving connectivity between cities.

Planes - Airbus (1970)

The French government supported the aerospace sector through subsidies, research funding, and coordination between European partners.

Creation of Airbus: Founded as a consortium of European aerospace companies, including France's Aérospatiale. Initial 1967 agreement included the British which withdrew.

Global Competitor: Airbus broke the monopoly of American manufacturers like Boeing, becoming one of the world's leading aircraft producers.

Innovation: Development of advanced aircraft models, such as the Airbus A380, the world's largest passenger airliner at its time of introduction

3. French failures

Concorde (1962)

A joint venture between the French and British governments to develop a supersonic passenger airliner.

Economic Viability: High development and operational costs made it unprofitable.

Limited Market: Noise restrictions and high ticket prices limited its appeal.

Outcome: The Concorde was eventually retired in 2003, marking a financial loss for both governments.

Plan Calcul (1966) / Unidata (1972)

The Plan Calcul was a French initiative launched in 1966 with the aim of building a French computing industry capable of competing with IBM and other American giants.

Motivation3

The leading French company “Bull” was losing ground to IBM

Mid-sixties, the Pentagon blocked the sale of a supercomputer to the Military Applications Division of the French Atomic Energy Commission

Why did the Plan Calcul fail?4

IBM had enormous resources for research, development, and marketing

Lack of focus whether the Plan Calcul should be on scientific and defense applications or on commercial computing

The decision to exclude Bull, France's most experienced computing company, from the main consortium due to General Electric’s 51% stake, further divided resources.

Many of the products were non-compatible with IBM’s widely adopted standards, limiting their appeal to a global market.

Unidata

All the limitations of the Plan Calcul listed above are related to reaching critical mass. Interestingly, there were efforts since 1972 to get critical mass through Unidata, a French-German-Dutch alliance between CII, Siemens, and Philipps. The project was framed as the “Airbus of information technology”5 and “Europe’s answer to the American challenge”.6 The former director of Plan Calcul has written a book in which he puts the blame for the failure of Unidata on politics and the death of Pompidou. His successor Giscard argued that the program was too expensive, the Americans too advanced, and the Germans too powerful in a Unidata alliance. In 1974 he defected from the alliance, abandoned the idea of European strategic autonomy on computers and instead opted for merging the French CII with the American Honeywell-Bull.7

The French alternative to the Internet (1978-2012)

Cyclades (1971-1981): Cyclades was a French packet-switching network designed by Louis Pouzin. It introduced the concept of datagrams, which became foundational in the development of the Internet Protocol (IP) adopted by the US ARPANET. Cyclades was defunded as the French national telecommunications administration (PTT) saw the network as a competitor to its own services, which used a circuit-switched approach and allowed for greater control over the network and billing. (longer explanation in the footnotes)8

Minitel (1978-2012): Minitel was a circuit-switched service launched by PTT. It was accessible through telephone lines, providing services like online directories, messaging, news, and e-commerce. Over 9 million terminals were distributed for free to households, making it one of the world's most successful pre-Internet online services. However, globally circuit-switched standards did not reach critical mass. The spread and network effects of packet-switched Internet standards led to the decline of Minitel, which was officially discontinued in 2012.

More recent digital efforts

Search Engine - Quaero (2005-2013): Quaero was a Franco-German project aimed at developing advanced multimedia and multilingual search engines to compete with Google. Already in 2006 the partners separated with Germany. Germany then separately unsuccessfully pursued THESEUS.

Cloud - Gaia-X (2020-present): Gaia-X is a joint French-German initiative to create a secure and federated European data infrastructure, aiming to establish digital sovereignty for Europe. Seeks to reduce dependency on non-European cloud providers by developing an open, transparent, and secure data ecosystem based on European standards and values.

4. Theories of failure

As argued in “Americans are from Musk, Europeans are from Greta”, it certainly feels like the US is accelerating and leaving Europe behind based on digital technology. This makes the question of why some French / European industrial policy efforts to close the technological gap have succeeded, whereas others have failed relevant. The following are my current hunches rather than clear answers, and I would encourage readers to share other views, ideas, and considerations.

Domain characteristics

It seems plausible that some types of industries may inherently be more suitable for some types of industrial policies. Two of three main French planning successes (nuclear & high-speed trains) are in areas close to natural monopolies and public utilities. Is it just an accident that the countries that perform the best on high-speed trains (China, Japan, France) are also countries with larger than average civilian nuclear industries? Or, that the neoliberal Anglo-Saxons have such mediocre trains?

Does the series of French failures in digital technology therefore imply that high-tech Colbertism does not work for digital technologies? It depends. Some digital technologies have high failure rates for start-ups and may be better suited to the risk-taking nature of venture capital portfolios than large-scale government funding. Further, the French decision to adopt virtual-circuit standards over packet-switching was a crucial mistake. Here, the technocratic instinct for control was prioritised over efficiency, which was a bad decision in the long-run.

However, it is also noteworthy that other models of digital industrial policy outside of France have been successful. For example, Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan all have successfully used industrial policy to not just protect their local industry but to have national champions in some digital aspects that compete on the global market. Why have they succeeded where France failed?

Market size

Unlike the United States or China, which benefit from large, unified markets and substantial resources, European countries often operate within fragmented markets due to linguistic, cultural, and regulatory differences. This fragmentation limits the ability of French companies to achieve the economies of scale necessary to compete globally, particularly in capital-intensive and high-tech industries.

European market: The logical response is the single European market and joint-European projects. However, as Unidata and other efforts show, these are often still dominated by national-level thinking.

Standards: For interconnection technologies and exporting beyond the domestic/European market, interoperability is key. It is notable that France has failed to adapt to or set global standards in a number of cases, which set them back. This has been true for the telegraph, to the Plan Calcul, to Minitel.

EU competition rules

From strategically concentrated to thinly spread support: With European integration and global competition, France's industrial policy shifted to align with EU norms. Emphasis moved from vertical, sector-specific interventions to horizontal policies supporting overall competitiveness.9

Fighting against “European champions”: EU competition rules remain a clear constraint on industrial policy and the support of “European champions” that are competitive on the global market. For example, in 2019, the European Commission rejected the merger between Alstom and Siemens concerning the railroad industry.

Lack of pragmatism: Sometimes there seems to be a lack of pragmatism in understanding that the rules are supposed to serve Europe, rather than Europe dogmatically serving the rules. For example, EU competition rules forced EDF to sell a portion of its nuclear-generated electricity to alternative suppliers at a regulated price, enabling them to compete with EDF in the retail market. The ARENH price was fixed at €42 per megawatt-hour (MWh), which was far below market rates during the European energy crisis, effectively allowing competitors to purchase publicly funded electricity at a lower cost and selling it for private profit.

Industrial planning capacity

Top-down innovation requires planners to pick the right industries and a support that fits the domain. The French political elite traditionally comes from the Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA). However, governments pipelines don’t necessarily seem to select and train individuals to lead high-tech Colbertist efforts.

ENA curriculum: The “énarques” are smart no doubt, but are they trained to administer industrial projects? My outside view is that the curriculum prioritizes referencing the right authors in conversations over practically relevant things for administering “grand projets” like industrial literacy and bottleneck-oriented management.

Technical backgrounds: Based on anecdotal evidence, it was more common to also have individuals with technical backgrounds join ENA and/or lead government projects in the past. For example:

Giscard first studied at the École Polytechnique and then ENA. He has been the last French president with something other than political science, law and ENA as background.

The French nuclear program was created and administered by engineers like Pierre Guillaumat (École polytechnique) and Marcel Boiteux (ENS).

5. Technocracy and dynamism

Overall, “feeling the Giscardpunk” is not meant as a specific commitment to the technologies of the time of Pompidou and Giscard, such as nuclear energy or supersonic passenger jets. “Feeling the Giscardpunk” is more of a vibe of European progress with some urgency.

Notably, high-tech Colbertism is also a form of top-down planning, which has its own challenges and downsides. In the three archetypes of

’s “The Future and Its Enemies”, it corresponds to technocracy. However, it is technocracy aligning with a dynamic vision of the future over a static vision.Thanks to Konrad Seifert for valuable feedback on a draft of this essay and introducing me to the concept of “Giscardpunk”. All opinions and mistakes are mine.

Accordingly, “Pompidoupunk” would seem to be the more accurate name for the French high-tech Colbertist aesthetic than “Giscardpunk”. Notably, Giscard also stopped the Plan Calcul / Unidata. Then again, it’s probably not worth it to be too sectarian about niche aesthetics, so I’m sticking to “Giscardpunk”.

Pierre Mounier-Kuhn. (1994). Le Plan Calcul, Bull et l'industrie des composants: les contradictions d'une stratégie. Revue Historique, 292(1), pp. 123-153.

Pierre Mounier-Kuhn. (1994). Le Plan Calcul, Bull et l'industrie des composants: les contradictions d'une stratégie. Revue Historique, 292(1), pp. 123-153.

Maurice Allègre. (2021). Souveraineté Technologique Française: Abandons & reconquête. VA Editions.

Der Tagesspiegel, 6.7.1973.

Maurice Allègre. (2021). Souveraineté Technologique Française: Abandons & reconquête. VA Editions. p. 85

Packet-switching means that data packets are sent individually over the network and may take different routes during a communication session between two computers. In contrast, in a circuit-switched network, such as the telephone network, a fixed data path is established between the two parties for the duration of the communication session.

Why is packet-switching useful? Distributed networks without a fixed communication path do have the highest survivability in the case of physical network disruptions. However, the big advantage of packet switching is simply efficiency in using network capacity. Resources are allocated dynamically and there are no idle resources in the form of reserved bandwidth for a circuit that is not fully used.

Why did many telecom companies not like packet-switching? Packet-switching follows the logic of “smart endpoints and dumb pipes”. In contrast, virtual circuits allowed telecom providers to maintain control over the network infrastructure, including routing and connection management. Without dedicated circuits, it becomes more complex to measure usage based on time or distance, complicating traditional billing practices and telecom companies were unable to charge premiums for dedicated connections threatening existing revenue streams.

Elie Cohen. (2007). Industrial Policies in France: The Old and the New. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 7, 213–227.; Pierre-André Buigues & Elie Cohen. (2020). The Failure of French Industrial Policy. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade

Very interesting article. And I must say that you have a talent for coming up with catchy titles for your articles. Giscardpunk!

I am curious how much the French government spent on each of these projects that you mentioned. The TGV and nuclear industry look pretty wise in hindsight. I think these put France in a much better economic position than the rest of Europe.

One problem Minitel had getting traction outside of France is many of France peer incumbent telecom providers like AT&T were under severe anti trust pressures and starting a Minitel type service would have only exacerbated them. In France at that time in particular this was not an issue.