On November 5th, the US will elect its 47th president. However, no matter which candidate wins, the new administration faces a crisis in democracy.

About 90% of surveyed voters in each party said the opposing party’s candidate would be likely to weaken democracy at least “somewhat” if elected

About 80% of surveyed Democrats and Republicans said the other party “poses a threat that if not stopped will destroy America as we know it.”

People increasingly refuse to date or be friends with someone supporting the other party. Fear of political violence and support for political violence are increasing

More insidiously, not everyone is unhappy that US democracy is in crisis. Curtis Yarvin’s ‘technomonarchy’ is a term that blends technology with monarchy, articulating his vision for a highly centralized, authoritarian form of governance powered by advanced technology. Yarvin, who initially published under the pseudonym Mencius Moldbug, is known for advocating a ‘dark enlightenment’ philosophy, which critiques democratic governance and argues for a return to forms of absolute rule.

The ideology is niche, but an increasing fraction of the American right seem to be open to post-democratic ideation. Peter Thiel famously already stated in 2009 “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” In the last few years, such ideation has notably accelerated with some celebrating the “Bronze Age Mindset” which says: “The only right government is military government, and every other form is both hypocritical and destructive of true freedom.”1 Similarly, Thiel protégé and US vice-presidential candidate J.D. Vance is at a minimum familiar with Curtis Yarvin’s argument that an oligarchic elite has captured the US and that only a “technomonarch” can implement the true will of the people.

This article takes a deep dive on Swiss democracy. As a Swiss I may be biased. However, Switzerland’s political system is not that well understood outside of Switzerland and it is worth looking at in this context for three main reasons.

First, Switzerland is in many ways much closer to the political system of the United States than examples commonly used by ‘technomonarchists’, such as the Roman Republic and Singapore.

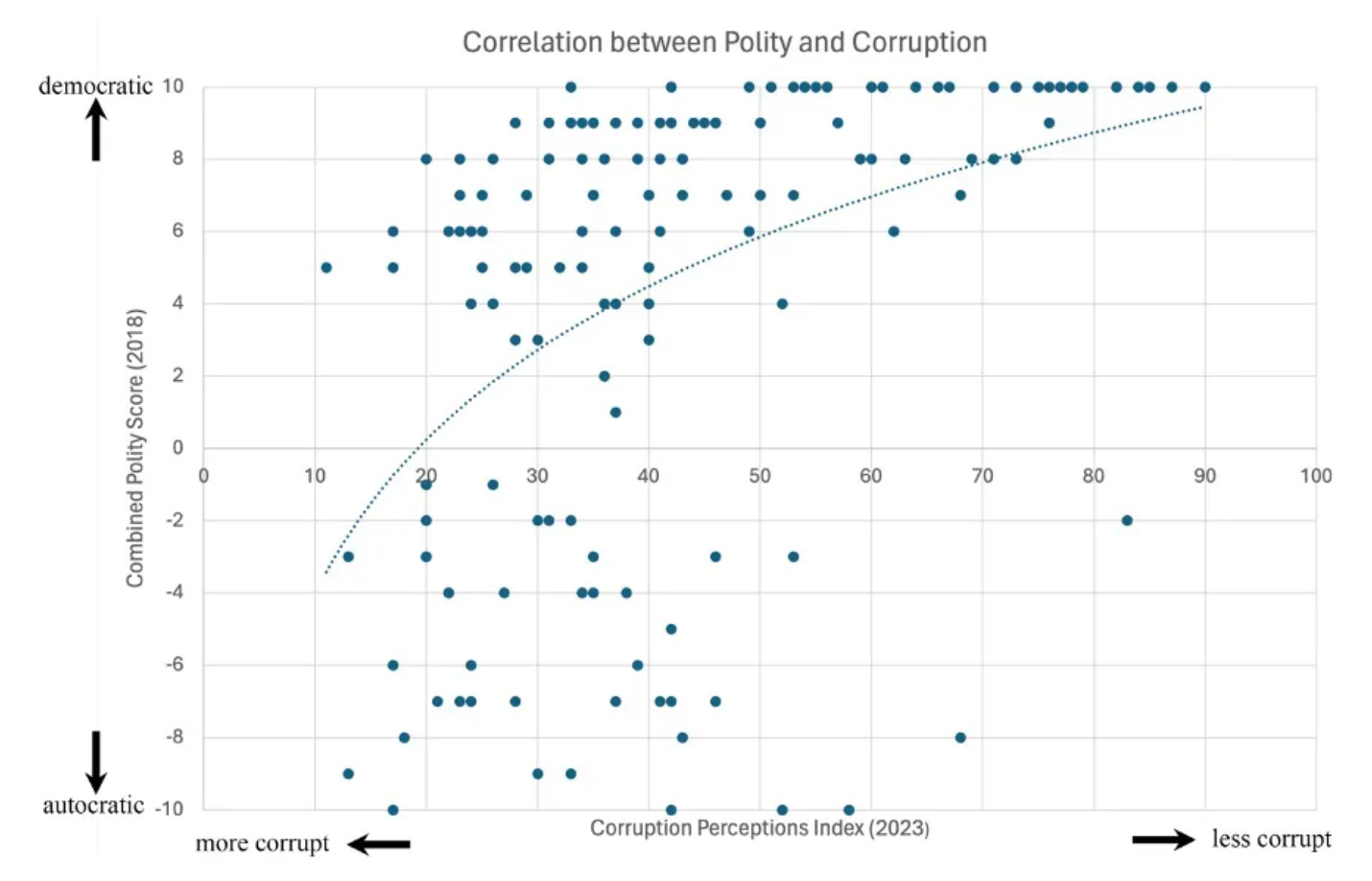

Second, Switzerland is a living proof that debunks some of the core claims of ‘technomonarchy’. Individual freedom and democracy are not just compatible, they can be mutually reinforcing.

Switzerland is Nr. 1 in the direct popular voting index of the Varieties of Democracy project. In Switzerland the population does not only vote on representatives but there are votes four times every year on specific issues. A Swiss can vote more often in one election cycle than most people living in democracies get to vote in their lifetimes.

Switzerland ranks Nr. 1 in the world in the Human Freedom Index created by the Cato Institute, Nr. 2 in the world in the Economic Freedom Index created by the Heritage Foundation.

Third, the Swiss political system is uniquely resilient to polarization spirals. As such, it can offer some lessons and inspiration for how to structurally reverse political polarisation and to truly give ‘power to the people’. Specifically, Switzerland shows that the stakes of elections in democracies do not have to be existential, and that there is a way to sustainably reduce the threat of disinformation without censorship.

So, let’s talk about it.

1. America is more like Switzerland than the Roman Republic or Singapore

The techno-monarchists like to compare the US to the late Roman Republic and say that now it’s time to switch to the Roman Empire. However, except for being the dominant Western power, the sociotechnical context of modern America is fundamentally different from the Roman Republic. For starters, the Roman Republic happened before the advent of modern telecommunications. So, the Roman Republic wasn’t really a democracy in the first place and a true democracy at scale would arguably not have been possible. Not mentioning that having the emperor changed by coup and civil war every couple of years, does not seem very appealing to me.

When Curtis Yarvin is asked for a more modern example of what a technomonarchist US should strive for, he invariably starts by mentioning Singapore and its founder and long-time leader Lee Kuan Yew (e.g., 1, 2, 3). I have studied at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore. I have great respect for Lee Kuan Yew and, in some aspects, there is a lot to learn from Singapore.2 However, Singapore is technocratic and paternalistic. So, it is a strange ‘blueprint for utopia’ coming from the same people that complain so much about ‘unelected bureaucracies’ and that emphasise libertarian ideals and individual freedom.

My sense is that most ‘technomonarchists’ have a pretty limited grasp of Singapore.3 In many ways the political system of the United States shares much more in common with Switzerland than with either the Roman Republic or Singapore.

Democracy: The idea that citizens should have a direct voice in governance is a common thread between the US and Switzerland. The refusal to bow to kings or dukes is a part of both our national mythmaking. The legitimacy of government is derived from the bottom-up. In the words of Abraham Lincoln: “government of the people, by the people, for the people”. The United States is the first modern democracy. Switzerland is the first modern direct democracy. Switzerland has been one of the main models studied by the US founding fathers for the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The American Model has been the main source of inspiration for the modern Swiss constitution written in 1848. Due to these mutual historical influences, the United States and Switzerland are also called ‘sister republics’.

Federalism as a core structure: In the United States, power is divided between the federal government and the individual states. In Switzerland the states, called Cantons, have even more relative power than in the US. For example, education and public health are primarily Cantonal matters in Switzerland. We call this core principle ‘subsidiarity’, meaning problems should be solved at the lowest level at which they can be efficiently solved. This allows systems to accommodate differences in regional cultures and preferences (Switzerland is small but we have four national languages!).

In contrast, Singapore as a city-state has no federalism and is arguably closer to forced uniformity. For example, Singapore has forced ethnic diversity quotas for housing and neighbourhoods, in that sense it is closer to ‘woke authoritarianism’ than whatever the right imagines Kamala Harris to be.

Freedom of speech: The first amendment guarantees American the right to free speech. In comparison to most European countries that ban symbols and books from ideologies designated as dangerous, Switzerland is much closer to the American free speech ideal.

The classes at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy were excellent, but it is noteworthy that some classrooms did have visible surveillance cameras in them.

Gun culture: Americans have the right to bear arms as guaranteed by the second amendment. Switzerland also has one of the highest rates of gun ownership amongst developed nations and its own gun culture. For example, European colleagues are usually a bit surprised when they first learn that in Zurich they get half a day off to celebrate the annual shooting contest for teenagers.

Singapore has one of the world’s strictest gun control legislations. I mean, chewing gums are illegal in Singapore. Did you really think they would let you keep your gun?

2. Democracy and individual freedom can mutually reinforce each other

Is it a coincidence that the first modern democracy (the United States) has also become a historic exception in its support of individual freedom? Is it a coincidence that the country that maybe has gone furthest in actually giving power to the people (Switzerland) also scores highest in the freedom of those people? I don’t think so.

Curtis Yarvin and Elon Musk both share a love for Doge. Doge can refer to a ‘funny dog cryptocurrency’ and ‘Department of Government Efficiency’. However, as Curtis Yarvin gleefully points out it’s also the name of the autocratic rulers of Venice, and has the same late Roman origin as ‘Il Duce’ - Mussolini. So, it seems worth pointing out then that the demise of Venetian Republic has been explained by economic nobel prize winner Daron Acemoglu due to inclusive institutions being captured by rent-seeking ruling elites that protect their narrow, entrenched economic interests. This is one of the central achilles heels of any “benevolent dictator” plan. Sooner or later, positive autocratic outliers are captured by self-serving ruling elites.

More broadly, education is a crucial determinant of ‘civic culture’ and participation in democratic politics. In Switzerland the population is expected to vote on complicated matters. This creates an incentive to provide strong public education. Switzerland also provides voters with key facts and the arguments of both sides through an accompanying voting booklet. In contrast, in many authoritarian regimes, an educated population is still seen more as a threat than as a necessity.

Democracy and fiscal responsibility

Thiel’s central claim in his 2009 essay is that a democracy that includes voting rights for women and welfare receivers irreversibly shifts society towards large government and collectivism and away from authentic human freedom.

This is in line with the low view that many elites have of their own fellow citizens. In the words of Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Silicon Valley’s largest venture capital firm, direct democracy would be a “horrow show”. I cordially invite Marc Andreessen to come visit Switzerland, the world’s closest equivalent to a direct democracy. Rather than voting yes on any short-term benefit, the Swiss voters are aware that they are also footing the bill for large expenses. The Swiss population has rejected expansions of the welfare state multiple times. For example:

The Swiss population rejected a popular initiative to increase the amount of mandatory holidays from 4 to 6 weeks.

The Swiss population rejected a Universal Basic Income that would have given all permanent resident adults 2’500 CHF per month

The Swiss population rejected an increase of the first pillar of the pension system (social security, pay-as-you-go) by 10%

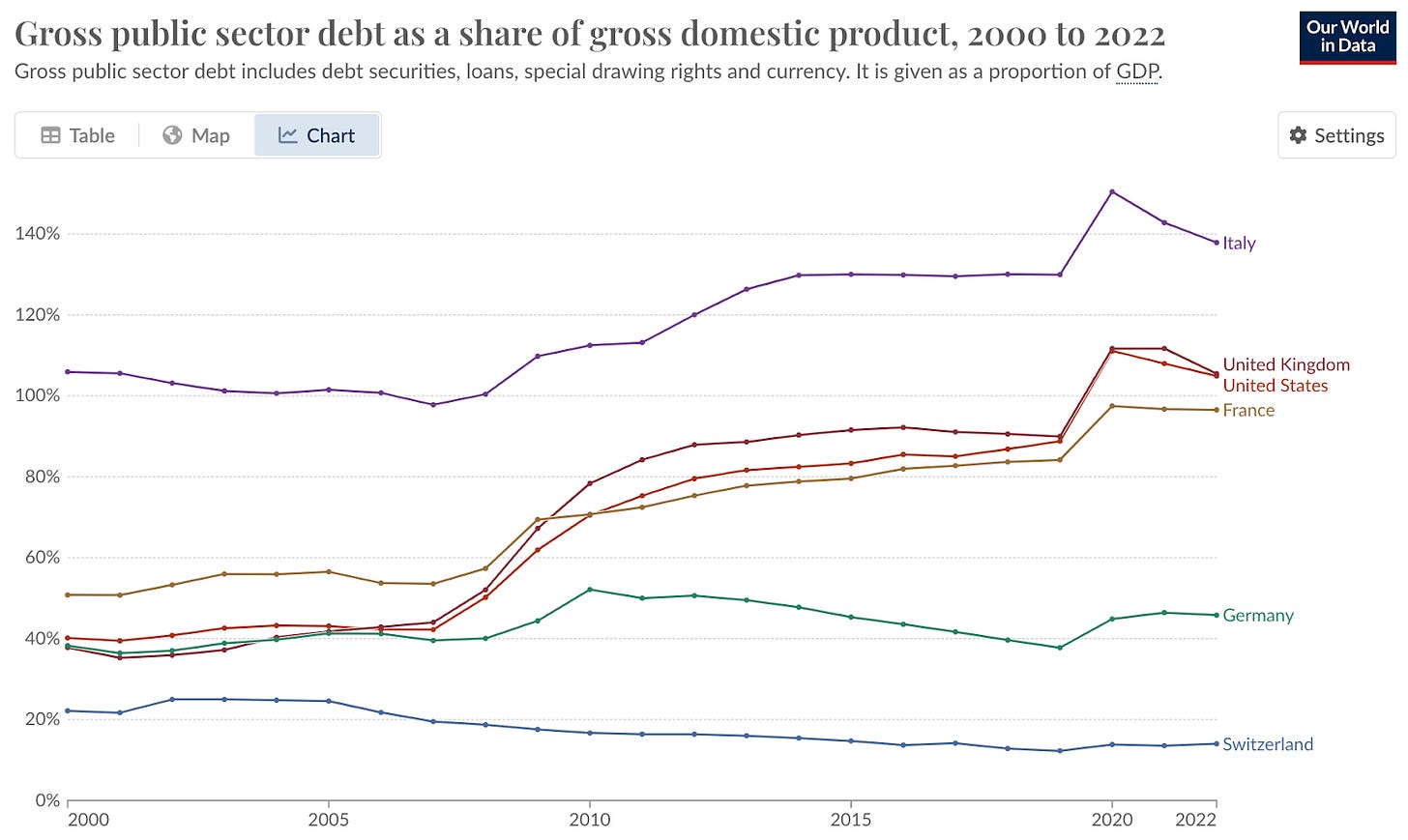

Also, for the record, the Swiss government is more fiscally responsible than most Western countries.

The people remain in their country for the rest of their life, and their children's life. It’s the politicians that are only in their role for four years and that sometimes like to spend like there is no tomorrow. The techno-monarchist ‘solution’ to this challenge is to install politicians as lifelong autocrats. The problem is just that by any statistic this removes accountability of politicians to the people, increases corruption, and wasteful spending. Do you believe populations would vote yes on spending their taxes on a billion USD+ summer palace for their leader? Or on 3’000 shoes for the wife of the dictator?

Switzerland has done the exact opposite of technomonarchism. It has reduced the fiscal leeway of politicians by adding a ‘debt brake’ to its constitution. In 2001, the Swiss population voted in favor of it with an overwhelming 85% support.

3. Democracy does not have to be the tyranny of the 51%

America seems caught in a polarisation spiral, where the other party is increasingly viewed as “the enemy from within”, and the other party gaining 51% is viewed as an existential threat. At this point a structural reform may be the only way to sustainable break this vicious cycle. Switzerland may be the country that is institutionally the furthest away from such a polarisation spiral. So, even if it may not be transferable directly to the American system. It may offer some inspiration:

Proportional voting: Okay, this is the obvious one and not unique to Switzerland. Still, it has to be said. The US has a “winner takes it all” system, in which the candidate with the most votes per district gets the seat / most votes per state gets all presidential electors. As a consequence, the US has a two party system in which all votes for third parties are essentially lost. Switzerland, like most European states, uses proportional representation. Each Canton has a number of parliamentary seats based on population and the seats are assigned proportionally to the Cantonal vote distribution. So e.g. in Canton Zurich with 35 seats, 3% of the vote is enough to get a seat. This means that there is room for a multi-party system. On top of that, Switzerland has an additional system where parties can combine their votes for leftover seats, so that votes for smaller parties are not lost.

Direct democracy: Swiss democracy is rooted in the concept of popular sovereignty. The people remain the highest decision-making body of the country. They have the final say. This means the population will vote on any changes of the constitution, any legislative act by parliament, which is opposed with enough signatures in a referendum, and any popular initiative, which is supported by enough signatures.

Representative executive: What’s most confusing to foreigners and maybe most unique to Switzerland is the executive. There is this old joke that the Swiss don’t know who their president is and it’s true. Because Switzerland does not have a president in a classic sense.

Federal Council: This council of 7 ministers with equal power is the highest executive decision-making body of the government. The Federal Council decides all matters by majority vote. Every year one of the 7 Federal Councillors is formally assigned as ‘the president’ to meet the presidents of other countries. However, this is purely ceremonial, there is no extra power.

Concordance: The Federal Council is elected by the parliament based on the concordance system. Specifically, the idea is that the executive should include all major political parties and be roughly proportional to their voting strength. Currently it consists of members of the four biggest parties from left to right. The same representative executive systems also exist at Cantonal and municipal levels. Although here it is more common to have 5-person executives

Collegiality: The Federal Council follows the ‘principle of collegiality’. The seven Councillors can and do have disagreements about issues. However, the Councillors abstain from publicly criticising one another and they are expected to represent the Federal Council as a whole towards the outside. Meaning, they are expected to publicly support all decisions of the council, even if they are against their own personal opinion or that of their political party.

Consequences

No extreme threshold effects: Does it make any sense to you that the daily mood of 20’000 voters somewhere in Michigan could completely change the course of a 300 million+ nation over all matters for four years? That’s absurd. In Switzerland changes in the executive and in policy are proportional to changes in the aggregated will of the people.

Expressing viewpoint diversity: One can predict the opinion of many US citizens on a dozen logically-not-linked issues just by knowing their stance on one issue. That’s the result of voting once every four years in a two-party system. In Switzerland the multi-party system and direct democracy allow voters to express a larger variety of political views.

Moderation incentives for politicians on the left and right: Because all parties will vote in Federal Councillors - not just your own party and its political allies - there is some pressure to pick moderate politicians for executive office from both the left and the right.

Institutional trust: The political institutions of Switzerland are always run by all major parties. As such neither weaponization of political institutions by ‘the incumbent’ nor the constant undermining of institutions by ‘the opposition’ are a prominent feature of Swiss politics. Switzerland has the highest trust in government amongst all OECD countries.

No negative ads: I have seen a bazillion ads for Swiss political candidates. I can recall only one negative Swiss ad against a politician and that backfired with the negative ad itself becoming the scandal and the newspaper that printed it subsequently apologising. Even the ‘firebrands’ of Swiss politics retain a level of cross-partisan respect that is foreign to US politics. Swiss politics is when Ueli Maurer, a rightwing Federal Councillor, still spontaneously offers his car to a leftwing politician so he can attend a ceremony of his daughter. Or, when young parliamentarians from the green party, the economically liberal party and the conservative party live together in a shared apartment.

Less vulnerability to disinformation: Sure, there is a need to think about labels for AI-generated or human-generated content and other technical measures. However, the most important thing to understand is that disinformation does not operate in a vacuum. It works to deepen existing societal wedges and cleavages. You will only believe disinformation that members of another political party have some evil plan, if you already think of them as an adversary. Foreign disinformation attempts about one of our Federal Councillors are mostly too far removed from the political reality of Switzerland to be believed by anyone in Switzerland.

Power to the people

Switzerland is the result of a confluence of unique geographic, social, and historical circumstances. It cannot be copy pasted. However, as US democracy is in crisis, maybe as a sister republic we can nevertheless offer some inspiration to our fellow freedom brothers and sisters. Even if it’s just to show that authoritarian determinism is a lie. Other democratic configurations, paths not taken by the US, are possible. And, as some conjure up a “Second American Revolution”, I do hope that Rousseau’s idea of the sovereignty of the people is not forgotten.

If you are genuinely worried that the people are losing power to an ‘oligarchic elite,’ taking away accountability to the people and giving unlimited power to a dictator and his ‘oligarchic counter-elite’ is a bad idea. The best way to give power to the people, is to give power to the people.

Costin Vlad Alamariu. (2018). Bronze Age Mindset. pp. 112-113.

For example, Singapore’s relentless drive for public cleanliness and safety or its excellent (non car-centric!) city planning with mass transit and electronic road pricing.

E.g. Curtis Yarvin: “Lee Kuan Yew comes to power, you know, the Caesar of Singapore, comes to power in a very similar way as the original Caesar.” Basic reality check: Caesar was a military general that marched on Rome. Lee Kuan Yew came to power through a mix of elections and Malaysia kicking out Singapore due to tensions between ethnic Malay and ethnic Chinese communities.

Fantastic! There is a massive difference between Switzerland and the Anglo Saxon system: in Switzerland there is system for power sharing. Elections are not about win or lose, but about your weight in a common government.

Switzerland is the most advanced form of “democracy beyond majoritarianism”

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zzr8Pgf7pMf6tTpbM/democracy-beyond-majoritarianism

I do not buy the Thiel technomonarchy at all, and I think the US could learn a lot from our sister republic, but there is one key difference: cultural homogeneity. I have a vague belief that it's extremely difficult to become a Swiss citizen, and as a result there is a rather long, continuous understanding of what it means to be Swiss though it evolves over time and creates its own factions. By contrast, the US is defined by heterogeneous culture, without many shared norms, especially post-1970s. The polarization is downstream of those trends, though the system exacerbates it and rewards ambitious politicians and polemicists for exploiting it. In so many ways, the US system is defined as building a system that can end zero-sum, blood-and-soil politics while still having a baseline identity of being an America with an overarching system that can accept multiple cultures.